'We've kept the whole damn country running': Pandemic deepens divide between haves and have-nots in U.S.

Inequalities widen as those cleaning, packing and delivering likeliest to lack benefits

A deadly pandemic is about to force a reckoning upon a nation whose cherished founding creed is that all people are created equal.

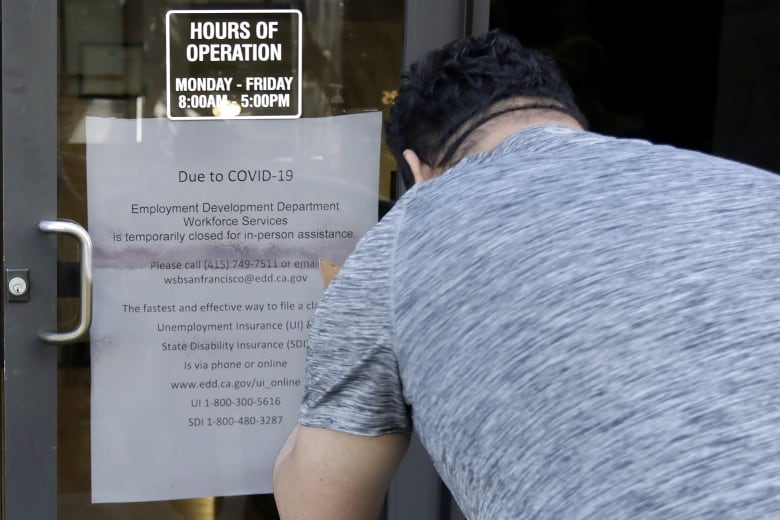

It's becoming clearer which Americans will shoulder an unequal share of the suffering from start to finish of the COVID-19 pandemic, as the United States becomes the new epicentre of it.

Poorer people are less likely to get tested early, to have health coverage, to be allowed to work from home, to get paid leave and to work or study from a video-streaming connection.

They are more likely to be packing groceries, washing buildings and encountering other people's germs while keeping the country running.

At the very onset of the crisis, it was apparent that not everyone enjoyed the same access to screening.

Until a couple of days ago, more players in the National Basketball Association (total population: 550) tested positive than the entire populace of West Virginia (population: 1.8 million).

Wealthy athletes paid for private tests. But in one of the poorest states, a resident told CBC News it's a no-brainer why there were zero reported cases until a few days ago: only a few dozen people had been tested.

"Because we don't go to the doctor," said Amy Jo Hutchison, a former preschool teacher, now an anti-poverty activist, in West Virginia's traditional steel-producing area.

"Because we can't afford to go to the doctor. We don't go to the doctor unless we think we're going to die."

As cases spread, the state has now promised coverage for tests and treatment for everyone.

Global problem with American twist

To be clear, inequality in pandemics is a global phenomenon — it's true in Canada today, and it was true of pandemics in the past, such as the Spanish flu, which tended to hit poor people hardest.

But this pandemic presents particular challenges in the U.S., which the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development ranks as one of the most unequal countries in the developed world.

It's partly driven by uneven access to health care.

Even before this crisis, nearly 10 per cent of Americans lacked it — and now, with rising joblessness, those numbers could explode, because nearly half of Americans get insurance through their jobs.

Washington lawmakers passed Friday a rescue bill that would expand unemployment insurance and provide up to $1,200 US per individual.

Walmart announced $300 bonuses for its hourly employees, whom company vice-president Dan Bartlett credited with rising to a historic occasion, telling Fox News: "Our workforce is really on the front line of this war."

The bonus program will cost the company $365 million, which is less than 0.1 per cent of Walmart's $514 billion in annual revenues last year.

Food banks, shelters struggling

Out on the street, the mere act of survival has gotten much more challenging.

Soup kitchens that serve the homeless are struggling with disrupted supply chains, and they're pleading for new donations.

A Washington, D.C., organization that normally has two dozen volunteers now has a few full-time staff, and they're working 14-hour days.

To limit transmission, the organization, Miriam's Kitchen, has cut back on volunteers and moved its operation to new outdoor tents.

"I am very afraid," said the group's chief executive officer, Scott Schenkelberg.

I am very fearful of what the next month or two will bring.- Scott Schenkelberg, CEO of Miriam's Kitchen

"I am very fearful of what the next month or two will bring."

He said the homeless who rely on public restrooms won't have the same access to cleaning products.

His own organization is struggling to get hand sanitizer and has heard from suppliers that there's a minimum two-week backlog.

At another non-profit across town, George Jones said he's never seen anything like this in 24 years running his poverty-support operation, Bread for the City.

"It's absolutely unprecedented," Jones said. "It's probably unprecedented for anyone who's alive right now."

Demand for food is surging, while supply chains are being disrupted. He said he's been calling grocery chains and farms seeking more food.

When asked about a controversy involving Washington politicians, Hutchison bursts out laughing.

After getting secret briefings in February about the severity of the upcoming crisis, several U.S. senators sold their stocks; one senator is being sued.

She said investors currently lamenting the performance of their 401(k)s (retirement portfolios offered by companies) are living in a world different from hers: "We're sitting around saying, 'What's a 401(k)?'" she said.

WATCH | How Canadians are helping each other during the COVID-19 crisis:

'We're the ones you rely on'

Hutchison recently gave Washington lawmakers an earful at a hearing about reduced poverty benefits.

She chided them for maintaining $40,000-a-year budgets to refurbish their congressional offices while she went to bed hungry, even with a preschool teacher's salary, so that her kids could eat seconds; nursed her gall bladder with essential oils and prayer; and chewed on cloves and ate ibuprofen "like Tic Tacs" because she lacked insurance.

She said this crisis is shedding a light on unheralded heroes.

Hutchison said she was talking to a worker at a Tim Hortons in West Virginia this week about how, under a state edict, he now provides an essential service.

"We've kept the whole damn country running," she said of the working poor.

"We're the ones you rely on. When everything's falling apart and breaking down, we're the ones you're calling essential employees.

"Maybe, this will be a huge wake-up call for people ... This is really going to be our moment, to start pushing back."

It makes no sense

She said she told the coffee shop employee that it makes no sense for people like him to be declared essential workers while struggling to make ends meet.

It's unquestionably true that the people working front-line jobs during this pandemic don't enjoy as many benefits as those currently telecommuting.

Just look at who lacks health coverage: the half-dozen most uninsured occupations include cooks, drivers, cashiers and building cleaners — some of the most vital people during the crisis.

As for who gets paid sick leave, only 11 U.S. states require employers to offer it.

Household cleaners and caregivers are going unpaid as people stay home.

And for people whose health care relies on the government-funded Medicaid program, some states allow coverage of COVID-19 treatment while others don't.

'The awakening of a sleeping giant'

Telecommuting is harder for the 21 million people without high-speed access in the U.S.; nearly one-fifth of teens say they can't complete all homework assignments because they lack a computer or internet. It's especially true for black teens.

Courtney Dowe has lived on both sides of the remote work divide.

Now, for the first time in her life, she has a job that allows telecommuting. She began it right in the nick of time. In February, she became a paralegal intern, and she gets her certificate next month.

Dowe was chronically homeless for years and travelled as a musician playing at subway stops and sidewalks around the country.

"I'm very aware of how extremely fortunate I am," said the 43-year-old Washington, D.C., woman. "This is the first time in my life I would have ever had this opportunity."

She has friends in a far worse state.

One is terrified of losing his housing; another, who provided security for a nightclub that shuttered, doesn't know what to do next.

A friend's mom who works as a house cleaner has been told not to come in if she's riding public transit.

The word that comes to mind is just 'devastation.'- Courtney Dowe, paralegal intern

"The word that comes to mind is just 'devastation,'" she said.

"There's no infrastructure to support this level of instability and level of need."

One thing that binds a few of the people interviewed for this story is a hope that when the short-term panic subsides and life slowly reverts to its less chaotic state, people will demand longer-term changes.

"This feels like the awakening of a sleeping giant," Jones said.