A democracy at a boiling point: The view from a U.S. swing county

In a sharply divided Michigan county, residents agree on one thing: fear of what comes after Nov. 3

A Donald Trump supporter is about to march across his street to confront someone who likens the U.S. president to a quasi-demonic biblical figure.

It's a late-summer Saturday morning in a suitable spot to take the temperature of American voters this election year: Grand Rapids, Mich., in Kent County, a swing county in a swing state.

And the temperature is approaching a boiling point as two men on the sidewalk seem on the verge of coming to blows.

It's a neighbourhood feud involving Brian Silvernail, the Trump supporter, who is white, and Justin Stewart, a local barber who is Black and who compares the president to a figure from the apocalyptic Book of Revelation.

It's a classic American cocktail: old grievances, embittered by politics, laced with the potent element of race.

Silvernail shares the backstory of their spat with a reporter in a mask-free monologue at close range, shrugging off the pandemic as overhyped, media-driven hysteria.

Trump campaign signs hang in the window and door of his home office.

Silvernail is an industrial real-estate agent who credits the president with an economic boom he's benefited from in Michigan's second-largest city.

"He's a businessman," Silvernail says of Trump. "He's an asshole, but that's the kind of guy I want representing me and negotiating [for the country]. If I'm in trouble, and I'm going down, I want a good attorney."

Silvernail is a precinct delegate for the Republican Party in his neighbourhood in the Nov. 3 election.

Stewart, on the other hand, sees cruelty in Trump's treatment of migrants at the Mexico-U.S. border and moves to strip health protections in the Affordable Care Act, and sees incompetence in Trump's response to the coronavirus pandemic.

Silvernail strides across the street as his neighbour eyes him coldly.

A glance at Kent County

The two men live in a county that feels like a postcard-sized snapshot of the U.S., cramming several political cultures into one tight space.

Kent County voted for Barack Obama once, then Michigan native Mitt Romney and Donald Trump, before swinging back to the Democrats in the 2018 gubernatorial race.

It has a vibrant, racially diverse downtown core — think yoga studios, craft-beer shops and sushi joints, with Pride flags fluttering over doorways.

Yet just a few minutes' drive away, outside Grand Rapids, past the suburbs, it's the other America: winding gravel roads, endless skies, farms and lots of Trump signs.

That microcosmic American mishmash is how you wind up with neighbours on the same street, in a different part of town from Silvernail's, hoisting a Black Lives Matter sign next to a Confederate flag.

NBC News has been regularly sending correspondents here in the belief that, as Kent County goes this fall, so goes Michigan, and as goes Michigan, so does the presidential election.

"It's a very good sample of the country," said Joel Freeman, head of the Republican Party chapter in the county, a traditional hub of moderate, establishment conservatives, such as the late U.S. president Gerald Ford, and mega-donors, such as the DeVos and Van Andel families.

The area has been trending toward the Democrats over the past generation.

The neighbourhood spat: A backstory

The idea of Democrats winning this election fills Silvernail with terror.

"I fear for my life if Biden wins," he said of Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden. "As a businessman and a white person."

Silvernail recently moved into a fast-gentrifying African-American neighbourhood, which is becoming wealthier and whiter. He says a Black tenant was forced to leave the building when he moved in, so that he could rent the apartment and adjoining commercial space together.

Meanwhile, the barbershop across the street has been a neighbourhood staple for 46 years and is still serving the area's longtime residents.

Stewart is one of the barbers at that shop and says the real people to fear in the U.S. these days are the white, armed militia types showing up carrying weapons to protests outside state legislatures — including in Oregon, Kentucky and here in Michigan.

"With rifles," Stewart said of the armed individuals. "And they say a Black man is violent."

Stewart says someone recently called the police on him just for milling near a commercial doorway — when all he was doing was sitting with his children.

Then came the death of George Floyd, a Black man who died after a white Minneapolis police officer knelt on his neck for nearly nine minutes.

Silvernail says tensions escalated afterward. Then he put up his Trump signs.

Right after that, Silvernail says, his car was badly smashed in an overnight hit-and-run. The next morning, he says, he found two things: the damaged car and, a few metres away, a note taped to his office window listing cases of anti-Black racism dating back to the 1921 Tulsa massacre.

He doesn't know who damaged his car. But he's about to cross the street to demand whether anyone at the barber shop has any information. He's considering broadcasting the confrontation on his Facebook page, which is filled with political messages and references to QAnon-themed conspiracies.

At the shop, patience with the vocal Trump supporter is wearing thin.

Stares follow Silvernail as he crosses the street.

"You're a broken soul," Stewart shouts. "God has a plan for you. … You may think you're winning now — but you're going to hell."

Friends try pulling Stewart away, to steer him from confrontation, but he keeps daring his neighbour to come one step closer.

Over at Democratic headquarters

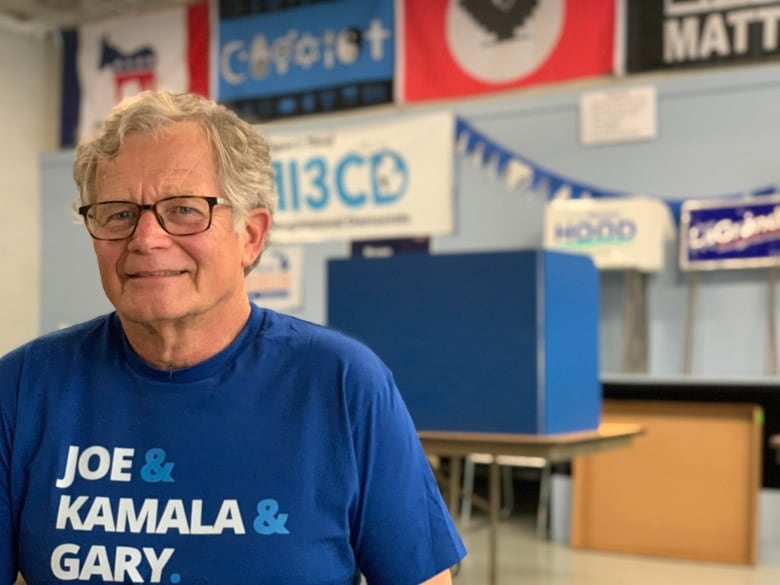

Speaking of sweltering infernos, in an old wooden warehouse across town, the Democratic Party's local campaign office lacks air conditioning.

Gary Stark comes to the office early on this August Saturday morning before the place gets too hot.

The Democratic Party's county chairman is also anxious about this election — uncommonly so, far more than in a typical election year.

He leads teams that have trained volunteers and prepared 10,000 packages with information about mail-in voting.

It's a far cry from his previous work.

Stark is a retired university dean. After the 2016 election, he felt depressed, and a tad remorseful, when Trump won Michigan by a mere 0.3 percentage points. Stark wondered if he could have done more to help elect Trump's opponent, Hillary Clinton.

He got involved as a party volunteer.

During an interview, Stark ran through a list of things he finds disgraceful about the president.

They include personal behaviour — "the narcissism ... the lack of empathy" — and policy, such as the intentional separation of migrant parents from their children.

But, really, his overriding fear involves what he sees as the steady strangulation of American democracy.

Namely, Stark takes issue with Trump:

- Using the justice system to pardon allies and repeatedly pushing to punish election opponents, both at home and abroad;

- Making cabinet appointments outside the legal rules;

- Suggesting the election should be delayed, or that people should try voting twice, which is illegal;

- Suggesting the winner should be declared before all mail ballots get counted; vowing to block money to the U.S. Postal Service;

- Firing federal auditors;

- Using the government to target media company owners;

- And drawing revenue from foreign and domestic governments at his family properties.

He now fears Trump can operate without guardrails because Republican lawmakers have made it almost universally clear they'll always defend him.

There's clear evidence close to home about what happens to a Republican who criticizes Trump: a member of Congress from this area, Justin Amash, left the party after calling Trump's conduct impeachable and sits as an Independent and will soon be out of politics.

Eroded institutions

After the interview ends, Stark raises something else about his biography: as a professor, his academic specialty was German history.

He said he feels like he's witnessing patterns familiar from the collapse of Germany's Weimar Republic, that bitterly divided, doomed democracy that dissolved into fascism

Stark doesn't hesitate when asked if he fears American democratic institutions are at risk of collapsing if Trump wins a second term.

"I'm convinced they are. They've already been eroded," he said.

He has plenty of company in articulating this fear. Just a few days earlier, at the Democratic convention, Barack Obama and others warned that American democracy could be on death's door.

In a popular book, How Democracies Die, Harvard political scientists argue the U.S. is experiencing a long-term democratic deterioration merely accelerated under Trump and is losing the two conditions necessary for a democracy to survive: forbearance, meaning self-restraint from leaders; and mutual toleration, or treating political opponents as decent, equal patriots — not existential enemies.

The book suggests both these pillars are crumbling in the U.S., and one of its co-authors, Steven Levitsky, said in a recent interview he's even more worried now than when the book came out in 2018.

Voting for Trump — but quietly

Kim Giese is getting ready for a walk with her kids at a waterfront park uptown. They're a conservative-leaning family, some of whom plan on voting for Trump.

She avoids discussing this at work.

Things got too uncomfortable after the 2016 election, said Giese, who voted for Trump. A colleague burst into tears and kept sobbing after Trump won, which drew a rebuke.

"Another worker just said, 'Cut it out, because some of us voted for him,'" Giese said.

"I think [the Clinton supporter] was flabbergasted that any of us voted for Trump — that anyone he knew voted for Trump."

She doesn't know if many people are changing their vote this year. Polls do suggest Trump is losing some centrist voters, and NBC's unofficial focus groups here in Grand Rapids have heard from a few.

This week, the former Republican governor of Michigan, Rick Snyder, who racked up monster vote margins in 2010 and 2014 in this county, wrote an op-ed announcing he'll vote for Biden.

'Fear beats anger'

Giese's family members share some misgivings about Trump.

Her 18-year-old son, Josiah, now entering university, calls the president "generally evil and self-serving" and "unfit."

He says Trump has few policies he likes except perhaps his tough rhetoric on the international stage.

So, who's he voting for? Probably Trump, he says. So is his sister, Kel, who fears Democrats are becoming too radical and blames them for recent rioting.

Josiah sums up the election dynamic in three words: anger versus fear.

The left, in his view, is running on anger toward Trump's authoritarianism, and the right is running on fear of left-wing radicalism.

"I think fear beats anger," Josiah said, predicting a Trump win.

His sister predicts a Biden win. Their mother isn't sure who'll win.

"If I was going to vote Republican, it would be out of fear for the radical change the left would bring," Josiah said.

When asked to elaborate, he mentions the violence seen at some of the protests against police brutality and says some Christian friends of his fear they can no longer express opinions on issues such as same-sex marriage.

Others fear the reparations for slavery that have long been debated might actually come to pass if Democrats get into power, and they'll be taxed as punishment for historical wrongs.

'Fixing it? I don't know'

The Grand Rapids street where Silvernail and Stewart confronted each other last month tells its own story about modern American politics.

It's like a long piece of connective tissue that unites factions of the modern Democratic Party: upper-class whites, young college-educated progressives and visible minorities.

As the neighbourhood shifts, the barber shop has survived.

But Stewart says he notices that some white neighbours walk faster as they pass the shop: "Like we're going to rob them, like we stink or something. I catch the vibe."

He adds: "We're good people."

Later that day, the shop is at peace. Customers fill the chairs and waiting area as a basketball game flashes on the television overhead.

The shouting ended a few minutes after it began without a punch being thrown, and everyone retreated to their corner of the street.

Stewart says he would never have thrown the first swing. He was ready, however, to throw the second and the third.

Asked whether things might ever be normal again with his neighbour, he answers: "We can be cordial, but fixing it? I don't know."

WATCH | In another swing state, Wisconsin, Trump and Biden both tried to address the recent bout of racial tensions and violence in visits to Kenosha this week: