3 reasons the COVID-19 death rate is higher in U.S. than Canada

Politics, health care and the Big Apple contributed to early gap, but it's narrowing

The nation next door has been a hot topic for Canadians during the coronavirus pandemic, with chatter frequently involving a certain politician who lives in a white Washington mansion.

The U.S. has a COVID-19 mortality rate about twice that of Canada's, with more than 200 deaths per million versus a little over 100 per million in Canada.

CBC News consulted five infectious disease experts, academic studies and data collected by governments and companies to try to find out why.

The overwhelming opinion points to three main contributors: longstanding issues related to health care, politics and one particular city.

While every expert agreed the U.S. government flubbed its early response to the pandemic, most said the administration of U.S. President Donald Trump was just one element in the bigger story.

The gap in fatalities between the U.S. and Canada is not a methodological quirk attributable to different reporting methods, the experts said.

The U.S. had 1.2 million confirmed cases of COVID-19, the illness caused by the novel coronavirus, and more than 71,000 deaths as of Tuesday night, and Canada had more than 63,000 cases and close to 4,300 deaths.

Death rates more reliable measure than cases

Mortality rates are considered a more accurate reflection of the rate of spread than case totals, which rely on inconsistent testing standards across jurisdictions.

"I think per capita deaths are a proxy for the extent of disease activity," said Ashleigh Tuite, an epidemiologist at the University of Toronto.

It's important to see the U.S.-Canada disparity in a global context, she said: U.S. death rates are still far lower than those in Spain, Italy and Belgium.

The difference in death rates between the U.S. and Canada could continue to change as the pandemic progresses. In fact, it has been steadily narrowing, according to data published each day by the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control,

In March, Americans were dying from COVID-19 at a per-capita rate 3.6 times higher than that of Canadians. In the first half of April, it was 3.1 times. It was 1.7 times in the last half of April. In early May, death rates have been similar.

Cases in the U.S. have already had a direct effect on Canadians. In Ontario, for example, the U.S. was by far the largest source of early imported cases.

The gap in outcomes opened up in March, when the virus hit New York.

New York, New York

The U.S. was unfortunate that its most bustling city got struck early.

"How prepared that initial city or geographic area was will influence your death rate," said Amesh Adalja, a pandemic preparedness fellow at Johns Hopkins University and Medicine in Baltimore.

Cities hit later benefited not only from being less crowded but from having more time to prepare, he said.

Without the Big Apple, the Canada-U.S. gap looks very different. Nearly half the difference disappears. Move beyond the suburbs of New York, and the Canada-U.S. death rates are even closer.

In fact, the death rate from COVID-19 is nearly identical between Canada and the 47 U.S. states that do not include a New York City suburb, based on state- and county-level data compiled by the site Worldometer.

Such comparisons are statistically dicey, however, because excluding one sub-national region distorts a country's demographics and urban-rural mix.

What's beyond dispute is that New York was clobbered by COVID-19, and one of its defining attributes — crowding — played a role.

New York has no rival in Canada when it comes to population density, which epidemiologists identify as a contributing risk. It has twice the density of Vancouver, Canada's most-crowded city.

Every weekday, 5.4 million people cram into New York's subway system, pushing its metal turnstiles and filling its cars, with a rail ridership more than six times that of Toronto's subway and streetcar system.

In early March, before many grasped the severity of the crisis, and before workplaces emptied out, infections rippled through the city, with the transit system a likely transmission vector.

An MIT researcher, Jeffrey Harris, described it in the title of a working paper, not yet peer-reviewed: "The subways seeded the massive coronavirus epidemic in New York."

New York City was "a fire that could be easily ignited," said John Brownstein, a Canadian-born epidemiologist at Harvard University and the Boston Children's Hospital.

Health access and pre-existing conditions

It's no secret underlying health conditions appear to make COVID-19 deadlier.

A report just released by the U.S. Centers For Disease Control found nearly three-quarters of those hospitalized in Georgia had pre-existing conditions believed to make COVID-19 more severe.

Hypertension was the most prevalent pre-existing health problem among people in the Georgia study: about 67.5 per cent had high blood pressure. Severe obesity was also on the list.

The U.S. has by far the highest obesity rate in the developed world and slightly higher rates of hypertension than Canada.

The Georgia study pointed to a wide racial disparity: 83 per cent of patients with coronavirus in hospitals it studied were African-American.

The CDC study is the latest indication of black Americans being hit harder than other population groups by COVID-19. (Comparable data for Canada is not yet available.)

WATCH | African Americans in Georgia have been hit disproportionately hard by the coronavirus:

This hints at some gaps in the U.S. health-care system that predated the pandemic. There's a persistent gap in access to care, for example, with visible minorities likelier to lack medical insurance.

Nearly 10 per cent of the American public lacked insurance before the pandemic, and that number is likely to grow as people lose jobs and employer-provided plans.

The U.S. government has promised to cover testing and treatment costs for the uninsured.

But anecdotes and analysis warn of people facing unexpected costs. In particular, minority groups and uninsured people must travel farther for tests, according to a paper Brownstein co-authored.

Minority groups, rural residents, homeless people and those struggling with mental health and addiction are less likely to receive care, according to Krutika Kuppalli, an infectious-disease expert at Stanford University.

"We are seeing high numbers in cities [and] areas where there are historically vulnerable populations," Kuppalli said.

"These types of patients are very difficult to engage in health care and are the most vulnerable."

Politics has an impact

Politics may have played a role in whether or not people practised physical distancing, some American studies suggest.

That's consistent with several U.S. public-opinion polls showing a partisan gap in attitudes about the pandemic, with Republicans less worried than Democrats.

People in counties that voted predominately for Trump in the 2016 election were less likely to perceive risk, seek information or practise physical distancing, according to a paper published last month by university researchers in Chicago and Texas.

"Even when, objectively speaking, death is on the line, partisan bias still colours beliefs about facts," study authors wrote. They say their paper, which is not yet peer-reviewed, accounted for differences in population density.

Another paper said what precautions individual Americans took against the virus may have been influenced by what they heard on political talk shows.

Viewers of one Fox News show hosted by Sean Hannity (who initially mocked the pandemic) were less likely to isolate than viewers of another Fox show hosted by Tucker Carlson (who took the threat seriously), according to the paper by researchers at the University of Chicago.

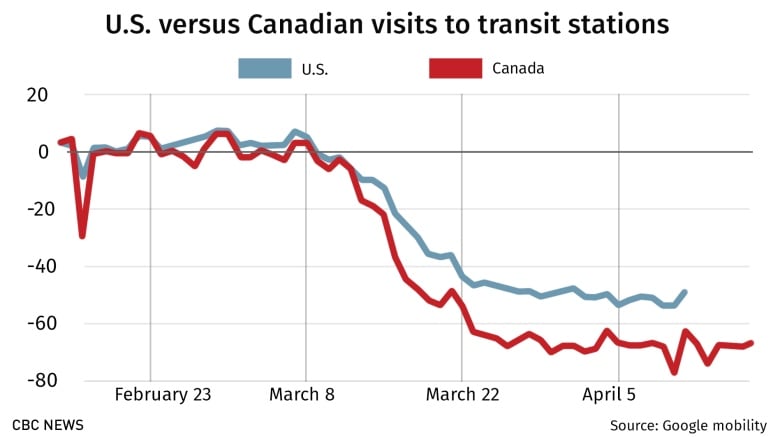

Tracking data collected by Google from smartphones suggests that Canadians practised more physical distancing than Americans and began doing it earlier.

Google's reports for Saskatchewan and Alberta show people in those provinces doing more distancing than people across the border in Montana and North Dakota.

Clear public communication is essential in a pandemic, said Saverio Stranges, chair of epidemiology and biostatistics at Western University in London.

Canadian politicians, while not perfect, tried delivering consistent messages at the federal and provincial levels, guided by public-health experts, he said.

In the U.S., Trump repeatedly clashed with state governors at various stages of the crisis — criticizing their performance, blasting some for reopening too slowly, and at one point also accusing a Republican ally in Georgia of reopening too quickly.

Several governors expressed frustration at the mixed-messaging and lack of co-ordinated response and made their own plans for procuring protective equipment and curbing the virus.

Trump was quicker in some aspects of his response than the Canadian government. He limited travel much earlier and U.S. federal agencies were quicker to recommend the use of masks.

Yet Trump's messaging ebbed and flowed on basic details such as the severity of the crisis.

In February, a month after he restricted travel from China, Trump was still insisting the U.S. would have zero cases soon.

In that same period, Canada's health minister was urging Canadians to stockpile food.

The White House is still blowing hot and cold about the threat level ahead, releasing a cautious plan for reopening, then encouraging protests in several states calling for immediate reopening of the economy.

The initial U.S. response to the pandemic was impeded by a testing debacle at the outset, but the country is now catching up to Canada in per-capita testing rates.

It has done 23,208 tests per million people compared to Canada's 24,359 per million.

"The federal response in the United States is definitely responsible for where we are," Adalja said. "You had from the beginning mismanagement and downplaying of the threat."