Meet the Canadian doctors working to identify and treat the rare blood clots linked to COVID-19 vaccines

A McMaster University lab that's studied clots for decades has become key to the country's efforts

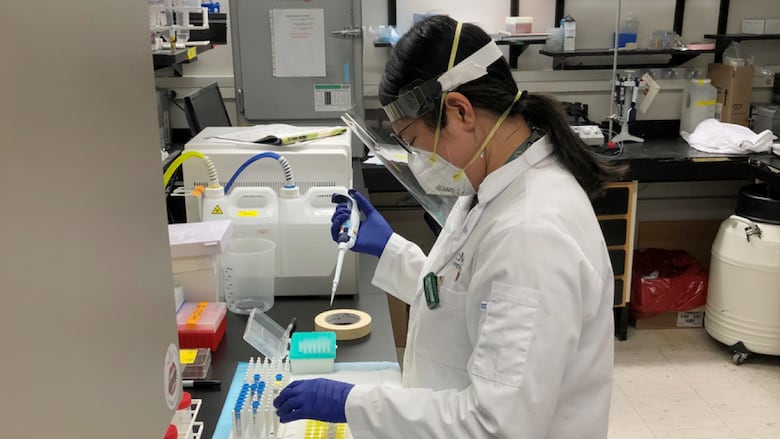

For decades, McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont., has been a hub for research on blood and its diseases — known as hematology — but in recent weeks it has taken on an even more prominent role in the field: working to identify the rare blood-clotting syndrome linked to certain COVID-19 vaccines.

The lab, a small space on the third floor of the university hospital, is the only one in Canada with the equipment and expertise to test for the syndrome, known as vaccine-induced prothrombotic immune thrombocytopenia, or VIPIT.

"It's not that huge, but it is the centre of the country right now," said Dr. Ishac Nazy, associate professor of medicine at McMaster and director of the McMaster Platelet Immunology Laboratory.

"When we realized that this was an issue, we set up a mechanism whereby if anyone in the country suspected that this would be the case, they sent us a sample and we processed that as quickly as possible."

So far, the lab has only tested about a dozen samples from across the country that are potentially linked to the AstraZeneca-Oxford vaccine. The test is completed within 24 to 48 hours.

Two people in Canada, a woman in Quebec and a man in Alberta, have had confirmed cases. Both received treatment and are recovering.

Dr. Menaka Pai, a clinical hematologist at McMaster who isn't affiliated with the lab, said being able to quickly identify the syndrome will be crucial in properly treating it.

Pai said the syndrome, VIPIT, occurs when the body's immune system begins to attack blood platelets, leading to clotting in the brain in some rare cases.

"If things happen, we can help with that. And I think that's a silver lining message," said Pai, a member of Ontario's COVID-19 Science Advisory Table.

The initial reports out of Europe, Pai pointed out, suggested a mortality rate of roughly 40 per cent blood clots linked to the AstraZeneca vaccine.

But Pai believes that rate is likely to be substantially reduced, as more cases are more quickly identified and the treatment of them improves.

A key aspect is avoiding heparin, a blood-thinning medication commonly used to treat some kinds of clots — but which seems to make VIPIT worse.

Hamilton lab in a 'unique position'

The lab's founders at McMaster were, in the 1970s, the first to discover heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, a clotting condition that can occur in patients given heparin.

The team now uses a variation of the same test to identify potential cases of VIPIT. Experts have warned against prescribing heparin in such cases.

"It just so happens that the blood clot issue that we're seeing with the vaccine is very much overlapping with one of these pretty rare platelet disorders that our lab has come to know very commonly," said Dr. Donald Arnold, a clinical hematologist who runs the lab with Nazy and Dr. John Kelton.

"We're in a very unique position where we're able to get the test done for these patients who are suspected of having a vaccine-induced clot and tell them pretty much within a day or two that we can confirm that is, in fact, the diagnosis."

WATCH | Dr. Ishac Nazy on how the lab test works:

Striving for better treatment

While the risk of blood clots is very rare, people who receive the AstraZeneca shot in Canada will be told to look out for symptoms, including severe headaches, abdominal pain, leg pain or shortness of breath.

Pai said health-care professionals in Canada, Europe and beyond have been in communication to discuss best practices for how to treat the syndrome.

Medical professionals across Canada, she said, have been advised to take caution in cases where a patient was recently vaccinated, and consult a hematologist if needed.

"We have to remember that this disease is only three-and-a-half weeks old, so at the beginning maybe people didn't know that you have to use a non-heparin blood thinner," she said.

"Now as we're learning more, and developing guidelines and sharing information, my hope is that this is going to become a disease that is much more responsive to treatment."

Benefits of vaccine outweigh the risks

Dr. Supriya Sharma, Health Canada's chief medical adviser, said last week the benefits of this vaccine clearly outweigh any risks.

"Get whatever vaccine is available to you. It's that simple. The longer you wait to get vaccinated, the longer you're not protected," Sharma said. "We know the risks of getting these side effects from the vaccine are very rare."

Based on evidence from the U.K., which has administered 20 million doses of AstraZeneca, Sharma said the chance of developing these clots is roughly one in 250,000.

The National Advisory Committee on Immunization has yet to update its advice that AstraZeneca not be used on patients under 55, although Ontario and Alberta have announced they will make the vaccine available to those 40 and over.

The issue of blood clots extended to the Johnson & Johnson vaccine last week. It uses the same technology as AstraZeneca but has a different formula.

The United States temporarily stopped using the vaccine after six people developed clots. More than 6.8 million doses have been administered in the U.S.

Health officials recommended suspending the vaccine in large part to inform doctors about what to look for and ensure the proper treatments are followed.

The first doses of Johnson & Johnson vaccine are expected to arrive in Canada at the end of the month.