'Police, drop your knife!': Sergeant who shot Pierre Coriolan questioned about final moments before his death

Coroner Luc Malouin and Coriolan family's lawyer both asked what police could have done to defuse situation

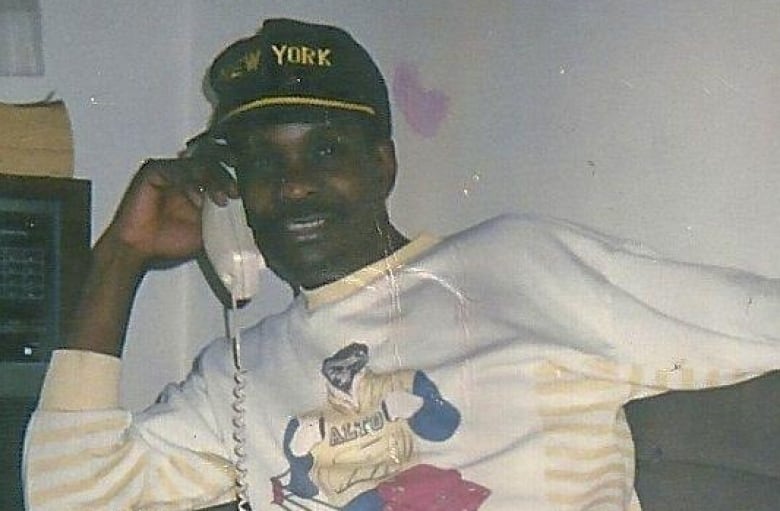

The police sergeant who shot twice at Pierre Coriolan told the inquest into the 58-year-old man's death he fired his gun because he believed there was an imminent threat, even though Coriolan was sitting in his apartment when officers approached.

Over the course of two days in a Montreal courtroom filled with lawyers, reporters and civil rights activists, Jimmy-Carl Michon faced repeated questions about the final minutes leading up to the shooting on June 27, 2017.

Coroner Luc Malouin and the Coriolan family's lawyer both asked Michon whether he could have done more to defuse the situation.

Michon said Thursday his priority was to find the suspect, isolate him and get him to drop his weapons — a screwdriver in one hand and a small steak knife in the other.

Michon was one of six officers who showed up at an apartment building in Montreal's Gay Village in response to 911 calls about a man in distress, smashing things with a stick inside his apartment and screaming.

The dispatcher had relayed to police that the man had mental health problems and was alone.

Michon told the inquest he couldn't be sure that the man was by himself and wanted to be certain no one was in danger.

With his gun drawn, he led the officers up the stairs to Coriolan's third-floor apartment. As they approached, they heard "screams of rage," he said.

'Police, drop your knife'

The door to Coriolan's unit was either wide open or slightly ajar, according to differing sworn statements from the officers. In his initial police report, Michon recalled the door being wide open.

When the officers first saw him, Coriolan was seated on his couch facing his television, holding the knife and screwdriver, Michon said.

"I told him, 'Police, drop your knife.'"

Coriolan refused to comply and appeared poised to run towards the officers, who were still in the corridor, Michon said.

One of the officers fired his Taser. It was ineffective. Another shot Coriolan in the thigh with a rubber bullet.

That's when Coriolan charged them, he said.

At that, Michon shot Coriolan twice. Another officer fired a single shot.

It's not clear which officer's bullet struck Coriolan in the stomach — the bullet that would prove fatal.

Malouin asked Michon if he had said anything else to Coriolan besides the initial order.

Michon said he didn't think so.

"I didn't have time," he said. "It happened very quickly."

The shots brought Coriolan to the ground, Michon said, but the man still tried to get up and make his way toward them.

"Ça prend un autre shot. Ça prend un autre shot," Michon said he told his fellow officers. ("It's going to take another shot.")

This time, the Taser worked. He was also struck with another rubber bullet, and a police baton.

He later died in hospital.

On Wednesday, Malouin asked Michon why he hadn't tried to speak to the distressed man in a calm manner when first coming into contact with him, rather than issue a command.

"I wouldn't want to be in your shoes," he said. But faced with someone in a mental crisis, "we try not to yell."

Michon, who has been a police officer with the SPVM for nearly 20 years, replied that 99.9 per cent of cases are handled in such a way, but he felt Coriolan presented an imminent threat.

Malouin returned to the same line of questioning Thursday, asking Michon what had stopped him from waiting outside the apartment for a few minutes, in order to see what Coriolan would do next.

After a long silence, Michon answered, "not necessarily anything."

Michon said it was the first time he had fired his gun on the job.

At sound of shots, sister broke down

Michon's testimony began Wednesday afternoon after an emotional moment at the inquest. That morning, the courtroom was shown a cellphone video of the incident that had been submitted as evidence.

As that video played and the gunshots rang out, Yolande Coriolan, one of Pierre's sisters, broke down crying.

"My God, my God, my God, why did you do that?" she asked, putting her hands over her face.

"Why did you do that? It's because he's black."

Michon showed little emotion as they watched the same video, but when facing questions from lawyers, he called the incident "a tragic event."

Quebec's Crown prosecutors' office announced last year it would not lay charges against any of the officers involved, following an investigation by the province's police watchdog, the BEI.

A lawsuit filed by Coriolan's family against the city, alleging that police were abusive and used unnecessary force, is working its way through the courts.

Yves Francoeur, the head of the Montreal police union, who has been attending the hearings, said the inquest is an opportunity to learn how to prevent such incidents in future.

But he stressed such interventions happen quickly and police need to take action based on the information they have.

"It's very easy to look at those situations when you are looking from your house or your office, but it always happens in very few seconds," he told CBC News.

The inquest is scheduled to continue through next week, and include testimony from the other officers at the scene and experts on dealing with people with mental health problems.

With files from Simon Nakonechny and Elias Abboud