Quebec cold cases: Families of 8 dead women call for public inquiry

Documentary filmmaker looking into unsolved deaths of women, girls from 1970s, 80s finds many stones unturned

The relatives of eight women who suffered violent deaths in the 1970s and early 1980s are calling on Quebec Public Security Minister Martin Coiteux to call a public inquiry into policing methods in the province.

-

Who killed Theresa Allore? SQ reopens investigation into 1978 cold case

-

Sûreté du Québec looks for clues in Nathalie Godbout cold case

For decades, those families have honoured the memory of their lost sisters and daughters, waiting for a call from police to confirm an arrest and, in some cases, becoming detectives themselves.

Now their hope has been renewed through the efforts of a Quebec filmmaker, Stéphan Parent, who is making a documentary about seven of those women, tentatively entitled Sept Femmes.

"We found [much] evidence was destroyed by police," Parent said.

Parent, who began investigating the unsolved homicide of 16-year-old Sharron Prior, noticed a pattern in other cold cases from the same era: destroyed evidence, relatives whose calls went unanswered, police forces that failed to communicate with one another.

Parent contacted former Liberal justice minister Marc Bellemare to help the families build a case for an inquiry.

The missing girls and women

The late 1970s were not an easy time to be a teenage girl or young woman in Quebec. Month after month, another was reported missing – and then found dead.

Among them:

Pointe–Saint-Charles: March 1975. Sharron Prior, 16, was on her way to have pizza with friends at a restaurant five minutes from her home. Her body was found three days later in the snow in Longueuil. No one has ever been arrested.

Chateauguay, two teenage girls are found killed: 12-year-old Norma O'Brien in July 1974 and 14-year-old Debbie Fisher in June 1975. A young man, a minor, confesses to the killings, though his name and the details are still cloaked in mystery.

Sherbrooke, March 1977: 20-year-old Louise Camirand is found in the snow, 11 days after stopping at a convenience story to buy milk and cigarettes. Her killer is never found.

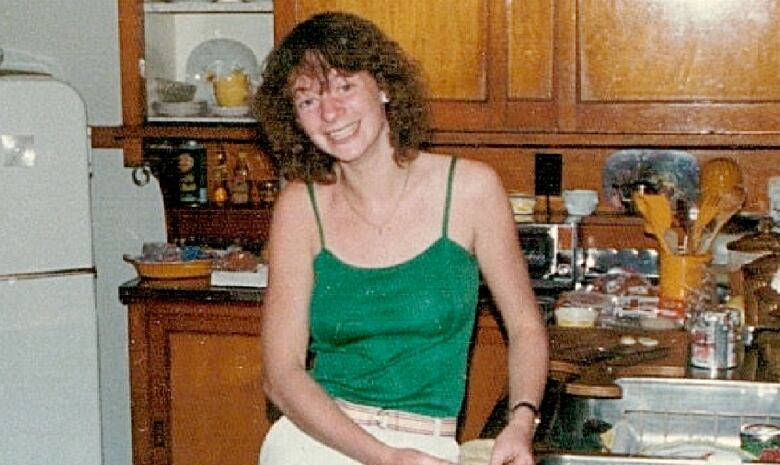

Montreal, June 1978: 17-year-old Lison Blais is found dead just metres from the entrance of the home where she lived with her parents on Christophe-Colomb Street. She'd left a disco bar on St-Laurent Boulevard early that morning. She had been raped and struck on the head, and there were choking marks on her neck.

Lennoxville, November 1978: 19-year-old Theresa Allore disappears from the campus of Champlain College, only to be found at the edge of the Coaticook River five months later. Police rule her death suspicious.

A serial killer?

"I think Quebec in that era was a very violent place," said John Allore, one of the relatives who is asking for a public inquiry.

"People got away with a lot more. In today's world, with cellphones and all this technology, cameras everywhere, it's not as easy to get away with these kind of behaviours."

His research shows there were 179 homicides in Quebec in 1977 and 177 the year before. In 2013, there were 68 homicides in the province.

The SQ won't confirm the statistics, but it's clear that in the 1970s, criminals were getting away with rape and even murder.

He said because police forces at the time worked in isolation, they failed to identify patterns.

If there was a serial killer on the loose in the greater Montreal area, as some relatives of the dead women believe, police didn't figure that out – or didn't share their suspicions with victims' families.

Change in attitudes

Lt. Martine Asselin, the spokeswoman for the SQ's cold case unit, acknowledges it was tougher then to solve cases.

"A lot of things have changed since those years: the evolution of the techniques and the evolution of the DNA and the way to treat the evidence has also changed," she said.

"The communications between the police forces is very present. We have a task force to manage serial killers or serial sexual assaults," Asselin said.

The cold case unit has recently added more officers, and Asselin said the provincial police force is looking seriously at these unsolved crimes. As for the decrease in the number of homicides over the years, Asselin credits improved police techniques, including those aimed at crime prevention.

John Allore agrees there has been a change in attitudes.

"Certainly, in the 1970s, rape and sexual assault were not taken as seriously then as they are today," Allore said. He said blaming the victim was the norm.

"A woman is found with a rope, a ligature around her neck, and police say it could have been suicide. A young girl is found abandoned in a field, and they say it could have been a hit and run."

My sister is found in her bra and underwear in a stream, and they say it could have been a drug overdose."

Inquiry demand focuses on 8 cases

The letter to the public security minister focuses on eight cases: Sharron Prior, Louise Camirand, Joanne Dorion, Hélène Monast, Denise Bazinet, Lison Blais, Theresa Allore and Roxanne Luce.

In it, the families ask for the following changes:

-

That all murders and disappearances anywhere in the province be investigated solely by the Sûreté du Québec.

-

That a protocol be established to make sure all evidence and information is held in a centralized place.

-

That police officers be paid to undergo specialized training.

-

That families of victims be kept systematically informed about the evolution of any investigation.

-

That families of victims, accompanied by their lawyers, have access to the complete dossiers of the investigations, if the crime is still not solved after 25 years.

A spokesperson for the Ministry of Public Security says officials are well aware of the difficult situation that relatives of missing or murdered people have to go through. The Ministry says it has received the letter asking for a public inquiry, and that demand is currently being analyzed.

with files from Sean Henry