There was no Manitoba in 1867, but there was a sense of uncertainty

Manitoba was still 3 years — and much political turmoil — away from being defined and joining the new Dominion

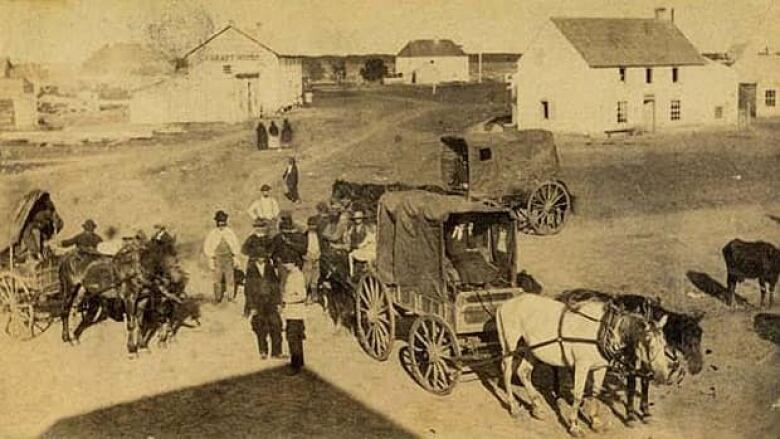

Wooden carts groaned over dirt paths, filling prairie air with creaks, grinds and rumbles as people in the Red River settlement went about a typical day on July 1, 1867 — tending small farm plots, selling grains, trading furs.

There were no bells, whistles or cheers to mirror the festivities in four eastern British colonies, which had just united to establish the Dominion of Canada.

Manitobans did not celebrate because there was no place called Manitoba.

The area that would eventually become the province was part of a continental commercial expanse known as Rupert's Land, owned by the Hudson's Bay Company.

Manitoba was still three years — and much political turmoil — away from being defined and joining Canada.

It was a land dotted by forts, homesteads and small settlements across a mostly empty rolling plain. There were no cities or towns.

The largest village, at the forks of the Red and Assiniboine rivers, was just a scattering of buildings, dirt roads, a stone fort and a population of about 100, according to the online digital archive site Manitobia.

Most of the wood-clad buildings that marked the fledgling community that would be known in a few years' time as Winnipeg were located near Upper Fort Garry, which overlooked the junction of the rivers.

Founded on the fur trade, which thrived there since the 1730s, the settlement's centre of commerce in 1867 was still focused around the forks, where steamboats brought travellers and trade.

Five years prior, in 1862, a man named Henry McKenney was ridiculed for purchasing a parcel of land covered in a tangle of scrub oak and poplar a quarter-mile north the forks. McKenney saw potential for a store where the north-south and east-west ox-cart paths crossed.

McKenney's site would eventually become the business and banking centre of the city at the intersection of Portage and Main.

In 1867, however, the celebrations out east created a general sense of uncertainty in the Prairies, both for those new to the region and those whose ancestors had lived there for generations.

A deal with the Dominion of Canada

In his book The Centennial History of Manitoba, James A. Jackson wrote that the HBC, which had domain over Rupert's Land since 1670, could also sense that uncertainty. Though it was still the primary trading company, it no longer held a monopoly and was also facing increased settlement and demands from Métis fighting for land titles.

The HBC's governors were increasingly aware they did not have the funds to administer such a large territory — and one that was evolving beyond simply a source of furs, according to Historica Canada.

The government of the newly created Canada, led by Prime Minister John A. Macdonald, was ready and willing to step in and relieve the HBC of its domain. Macdonald worried the United States, which had purchased Alaska from Russia in 1867, was interested in annexing Rupert's Land for itself.

In March 1869, the HBC agreed to sell Rupert's Land to the Dominion of Canada. Anticipating the transfer of these lands, the federal government sent surveyors out to assess and re-stake the lands.

Métis take a stand

The Métis of the Red River valley, seeing their concerns and land claims ignored by the new authority, took a stand and thrust the small settlement into a national spotlight. In October 1869, an eloquent, educated and articulate 24-year-old Métis leader named Louis Riel stepped on the surveyors' chain, said "You go no further," and halted the work.

In November, Riel and the Métis National Committee seized Upper Fort Garry from the HBC and established itself as the provisional government of the Red River settlement, responsible for negotiating the terms of the colony's annexation to Canada.

During negotiations with the Canadian government, a group of men opposed to Riel and the MNC prepared to attack but were captured and jailed.

Among them was a combative man from Ontario named Thomas Scott, who continually insulted the guards and threatened to shoot Riel if he was ever freed. Scott was sent before a tribunal, convicted of treason, and sentenced to death.

He was executed by a firing squad in the courtyard of Upper Fort Garry.

- Canada, A People's History: The execution of Thomas Scott

- Canada, A People's History: Manitoba is created

Manitoba becomes a province

The Manitoba Act, creating the new province and bringing into confederation, was passed by the Canadian Parliament and received royal assent on May 12, 1870.

At the time, Manitoba was a postage-stamp version of its future size. Much of what we know now as the province was still within the boundary of the North-Western Territories — which would itself become part of Canada as the North-West Territories in July of 1870.

Most of the new province's 12,000 citizens lived in small settlements and farms strung along rivers, close to sources of water and wood, neither of which could be found on the rolling plains.

Riel had achieved his goal but it was not a victory he could enjoy for long. Scott's death had inflamed passions in Ontario and Macdonald dispatched a military force west to avenge the killing.

Broken promises and dark history

Riel and his lieutenants fled just before the troops arrived in August 1870. With the MNC effectively disbanded and the leaders in exile, the government reneged on the promised transfer of land to the Métis people.

Instead, the land was opened to settlers from the east.

That led to another dark time in the province's young history as the government forced the Indigenous people onto reservations through treaties signed between 1871 and 1906.

Manitoba, meanwhile, continued to grow. By 1881, the population of the province was 66,000, by 1901 it was 255,000 and by 1911 it stood at 450,000, according to Manitobia.

By 1911, Winnipeg was the third-largest city in the country, with over 142,000 residents.

And today, as Canada celebrates the 150th anniversary of Confederation, Manitoba boasts a population of nearly 1.3 million.

Winnipeg stands as the nation's seventh-largest city, with a population of 705,000 — a long way from the 100 or so people who lived in that scattering of buildings and travelled those dirt roads in 1867.