How Marc Emery turned to marijuana activism

The Prince of Pot's early years

When Marc Emery returns to Canada later this summer, after nearly five years in U.S. prisons, Canada's "prince of pot" says he will feel triumphant. And not the least bit repentant.

"I'm proud of everything I've done," he told CBC News from Tensas Parish Detention Centre in Louisiana.

After all, smoking marijuana is now legal in Washington and Colorado, and other states have moved towards decriminalization and the legal use of medical marijuana.

What’s more, opinion polls suggest a majority in the U.S. and Canada want the pot laws relaxed.

In many respects, Emery provided seed money for many of the campaigns that advocated for more lax pot laws, and has said he can’t wait to "resume the unfinished battle to finish off marijuana prohibition."

- Marc Emery, B.C.'s 'prince of pot,' returns to Canada Aug. 12

- Marc Emery vows 'political revenge' against Tories

A lifelong activist, Emery did his first political campaigning in the 1968 federal election, which was won by Pierre Trudeau’s Liberals. Emery and his father had worked unsuccessfully to get the NDP candidate elected in their home riding of London East in Ontario.

Around the same time, Emery had started his first business, Stamp Treasure, selling stamps by mail.

By age 10, he had already found the two passions of his life, politics and business. They were also the two things that would lead to him getting jailed numerous times in Canada, and then in the U.S.

'Grew up with a lot of love'

Emery's working-class parents, Alfred and Eileen, moved to Canada from England before he was born. His father was a United Auto Workers employee at the 3M factory in London, where he worked all his adult life in Canada, according to Marc.

Emery says he "grew up with a lot of love, and my dad and mom really liked me, and were fans of mine and were always so encouraging."

In Marc Emery: Messing up the System, a 1992 documentary by Christopher Doty, Emery says that while growing up, "there was no such thing as limitations on one's capabilities."

By 1970, he was running his own mail-order used comic book operation. In 1975, he dropped out of high school to become a full-time entrepreneur, selling his comic book business and buying the London Used Book Mart, which he would rename City Lights Bookshop.

Vancouver pot activist David Malmo-Levine describes Emery as a voracious reader, and figures he has been for years. (Emery says his own memory is very sharp and he "can remember everything.")

From NDPer to libertarian

Following the 1979 federal election, in which Emery put considerable effort into another unsuccessful NDP campaign in London East, he began to read Ayn Rand, the American philosopher and novelist.

Rand, he said in a 2007 documentary, changed his life and the "whole way I look at everything." Emery, in his own words, became "Howard Roark personified," a reference to the protagonist in The Fountainhead, one of Rand's best-known novels.

He proceeded to read everything by Rand, who has "certainly been the most profound influence" in his life.

"All my actions since that time have been based on the philosophy I learned by reading her works," he told an interviewer in 2008.

Within a few months, Emery left the NDP and joined the Libertarian Party, running for its leadership, finishing second; he was its candidate in the 1980 federal election. Emery received just 197 votes, but that was more than double what the party received in 1979.

He also founded a weekly newspaper, The London Tribune, which lasted less than a year. And he was now "hell-bent to smash the state and expose collectivism," as he put it a quarter-century later.

Back then, his first target was the mandatory London Business Improvement Association's $32-a-year tax. But he quickly moved to take on the censorship of pornography (he called his opponents "fascist feminists”).

‘Defender of free enterprise’

During the early eighties, Emery ran unsuccessfully for London alderman, got high on marijuana for the first time and fell in love.

That was with Sandra Chrysler, who in 2004 Emery would describe as the love of his life (with the woman who was about to become the love of his life, Jodie Emery, looking on). Marc Emery told CBC News he first smoked pot in 1973 but didn't get stoned. That wouldn't happen until the next time he tried it, with Chrysler, at least seven years later.

Emery, Chrysler and her two children were together for seven years.

During that period, in 1984, he helped found the Freedom Party of Ontario (FPO), along with Robert Metz, another libertarian. Emery became the party's "action director" and Metz the president.

In the 1992 documentary, Metz says, "Marc wants to save the country singlehandedly, and almost believes he can do it." Then he adds: "This is the tragedy and the absolute marvel of Marc Emery."

Emery's next target, in 1984, was a proposed city tax to fund a bid for the 1991 Pan Am Games. In 1986 he opposed a garbage strike by city workers and the ban on Sunday shopping. In that battle, Emery eventually triumphed, but not before he was charged eight times and jailed for three days in 1988.

At the time, Emery described himself as a "defender of free enterprise against oppressive laws."

Meanwhile, Emery gained both fans and enemies in London. In a TV debate, then-deputy mayor Jack Burghardt called Emery "the biggest self-server in the city of London."

He's also proving to be a skilled media strategist. London Free Press journalist Herman Gooden called him a megalomaniac. "No small part of that is propelled by an ego that's gotta be responsible for 40 per cent of his body weight," Gooden said.

The marijuana cause

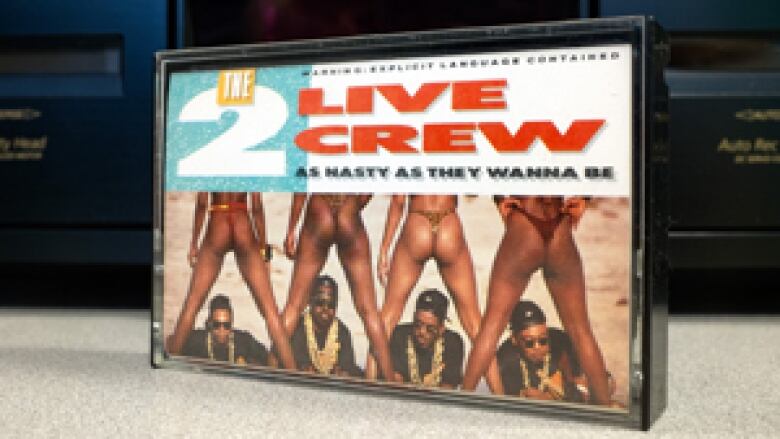

Emery next ran afoul of the law in 1990, for selling banned music. That was in protest after a record store owner was convicted for selling the 1989 rap album As Nasty As They Wanna Be by 2 Live Crew. Emery was eventually convicted of selling obscene material.

Meanwhile, Emery was becoming disillusioned with politics and the electoral system. He quit the FPO and, during the 1991 municipal election, organized a "burn your ballot" campaign.

Later that year, at 33, Emery embarked on his first campaign around the marijuana issue. But for Emery, the target was once again censorship.

In 1988, Parliament, with near-unanimous support, banned literature that promoted, encouraged or advocated "the production, preparation or consumption of illicit drugs."

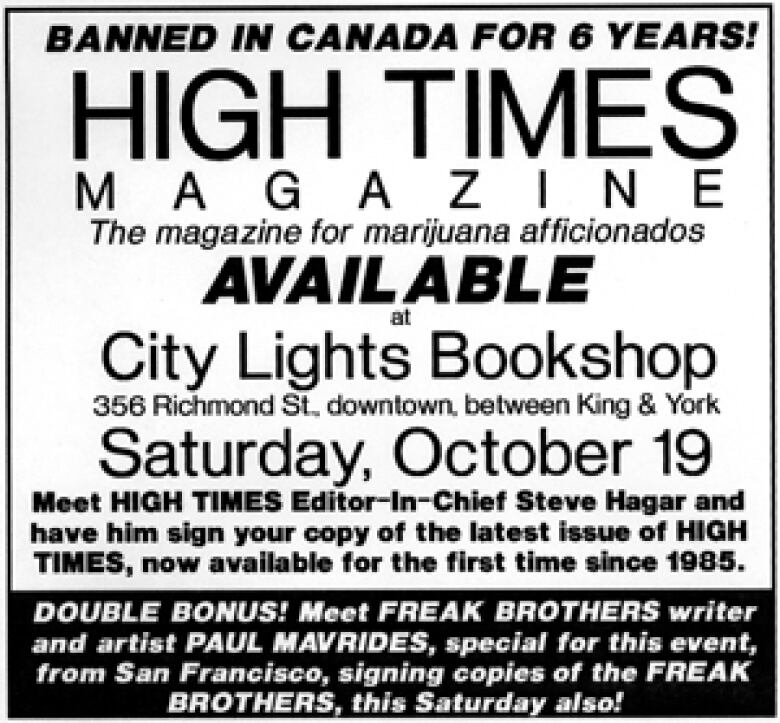

To protest the law, Emery sold books and magazines about marijuana and hemp at his bookstore, expecting to get arrested. But the London police didn't cooperate.

Then Emery opted to give away High Times magazine in front of police headquarters, but still no arrest.

In 1994, the literature ban was overturned in an Ontario court (it remains in effect in the rest of Canada), with Emery helping finance the defendant, Umberto Iorfida, of the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws in Canada.

Left Canada

In 1992 Emery sold his bookstore and, as he put it, "in a pout [with] no plans to return," left Canada with his second common-law wife, Debbie Newman, and her two children, heading for what he termed "exile" in Asia.

He soon lost all his savings in a shady investment in a house-building project in Indonesia.

He returned to Canada in 1994 with a sense of defeat, but he did have a plan, albeit one that eventually led to his imprisonment in the U.S.

"Determined to build a movement that used a retail model to generate money that would feed a vast network of activism," Emery and his family moved to Vancouver where he launched his campaign to "overgrow the government."

He started with Hemp BC, a store selling pot paraphernalia and books, and then a few months later began Marc Emery Direct Marijuana Seeds, which quickly became a multimillion dollar business.

That began the next chapter in Emery's life, but that's a story for another time. (For more about Emery's Vancouver years, click on the link to the 2008 video, "Canada's Prince of Pot.")

The profits from his new businesses funded his campaigning for pot legalization.

Aware that Emery was giving millions of dollars to pot activists in the U.S., the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency requested his extradition in 2005, which the federal Liberal government allowed.

The DEA called his arrest "a significant blow... to the marijuana legalization movement," but what they got him on was selling seeds to customers in the U.S.

Noting the changes to marijuana laws in U.S. states, Emery says, "The money I sent from the sale of those seeds has turned into exactly what I'd hoped: seed money to overgrow the government."

As his activist-collaborator Malmo-Levine told CBC News, "he's a pot activist because he saw the pot issue as being the easiest one to explain his concept of freedom to other people."