Alberta government must overhaul committee reviewing domestic-violence deaths, experts say

Vague recommendations often don't lead to meaningful change: victim advocate

This story is part of Stopping Domestic Violence, a CBC News series looking at the crisis of intimate partner violence in Canada and what can be done to end it.

It is unlikely, the committee said, that she knew of his past: The long history of assaulting his girlfriends, the threats he routinely made to kill them if they left him.

The no-contact court orders issued and consistently violated, the labels various government agencies gave him — "high-risk," "an unacceptable risk to persons close to him."

How he had once followed through on one of his threats and tried to murder his partner.

In 2012, after they had dated for several years, it was she he came for, stabbing her several times. Police discovered her body and, later, his.

The details surrounding the murder-suicide are contained in a case report from Alberta's Family Violence Death Review Committee, quietly posted on a government website in July 2019.

The report, which does not identify the victim or perpetrator, received no media attention. Its recommendations for how the province might prevent similar tragedies has not yet produced a public response from the government.

Experts say the committee's work is vital but often falls short, culminating in belated reports full of sometimes vague recommendations that the province does not act on in any meaningful way.

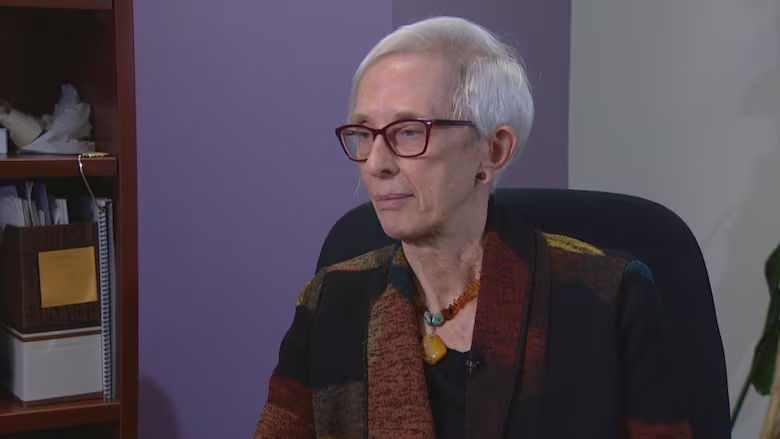

"It has not met expectations," Alberta Council of Women's Shelters executive director Jan Reimer said.

"We all know there needs to be more education, we all know there needs to be more prevention, we all know there need to be more resources in Indigenous communities," she said.

"There is lots we know. What are the actions that we are going to take and how are you going to monitor it to make a difference?"

Not every death reviewed

The committee was established in 2013 when the province amended the Protection Against Family Violence Act. Its members all have expertise in the area of family violence, and include lawyers, police officers, mental health experts, and victim advocates.

The committee produces annual reports containing statistics on domestic-violence homicides in the province, as well as in-depth reports on specific cases that represent systemic issues.

Those in-depth reviews cannot identify the parties involved and can only be conducted after any criminal investigations or proceedings are finished.

Since its inception six years ago, the committee has produced eight case reports. In 2018 alone, 23 Albertans died in family-violence-related incidents.

"I think case reviews should be done for each and every family-violence-related death that happens in Alberta," University of Calgary law professor Jennifer Koshan said.

Koshan leads a research team that is conducting a five-year study of access to justice in domestic-violence cases across Canada.

It is critical to "systematically track those deaths, investigate those deaths in detail, and see where not just the legal system but other support systems for domestic-violence victims may have failed in those cases," Koshan said, adding that other jurisdictions, like Ontario, investigate every death attributed to domestic violence.

A lack of resources is likely a factor in the committee's output of case reports, Koshan said.

In 2018, the province paid the committee's 10 members a combined total of less than $17,000 in compensation.

Community and Social Services Minister Rajan Sawhney declined an interview request.

In an emailed statement, her press secretary, Diane Carter, confirmed the 2019 budget for the committee was $554,000, the majority of which went to administrative staff whose work supports the committee. Carter said the ministry anticipates this year's committee budget will remain the same.

In response to the criticism the committee has released few reports, Carter said its investigations require an analysis of complex information.

She said these case reports are posted on the government's website and are tabled in the legislature, and responses from relevant ministries are also posted online.

"Our government has a longstanding cross-ministry working group called the Interdepartmental Committee on Family Violence, which is dedicated to preventing and addressing family violence," she said.

"Part of the (working group's) mandate is to implement and monitor the recommendations from the committee. Many of the committee's recommendations align with work already underway in government, and help us to prioritize our efforts in the prevention of family violence."

Political independence would help, chair says

Committee chair Allen Benson said while the committee has only produced eight in-depth case reports, it examines every domestic violence death before selecting certain ones for a deeper analysis.

Other jurisdictions that review every death use a checklist system — one that simply identifies whether certain indicators of violence were present leading up to the death — and don't get into the level of detail Alberta's committee does in its case reports, he said.

"The amount of files that have to be reviewed, we are talking in the hundreds in some cases," said Benson, who has chaired the committee since it was formed. "One of the most recent cases, I would say we had about 15 boxes of files to review.

"So there is a lot of work that is involved. The analysis part alone takes months."

Sometimes case investigations can take a while to begin, he said, because the committee must wait for investigation reports and forensic test results from police, sometimes for a year or more.

Benson was quick to laud the work the committee members and support staff do with the budget they have. He acknowledged, however, that additional resources would help, as would independence from government.

"The cost of running an independent committee and the cost of hiring the staff that are needed to do the work, I'm not sure that there has ever been an interest on behalf of any government to spend that kind of money," he said.

"I think if the Family Violence Death Review Committee reported directly to the legislature and was independent of government under new legislation, yes it would be more effective."

He said he would like to see the government bring more public attention to the committee and its work, and act on more of its recommendations.

"When we look at some of the family violence recommendations, we have seen a response that has been very positive," Benson said but added that "we haven't seen major changes in some of the policy areas that we would like to see.

"So I don't know that any government has responded properly to the recommendations that are being made by family violence death reviews anywhere in Canada," he said.

Committee recommendations not publicly tracked

In its case report of the 2012 murder-suicide, the committee recommended the Alberta government develop more supports for domestic violence victims and perpetrators, including supports focused on mental health and rehabilitating offenders, as well as the implementation of a "coordinated services model" to address family violence in Alberta.

Such sweeping recommendations can be difficult to implement, critics say, because they sometimes don't prescribe a clear course of action and the recommendations do not appear to be publicly tracked in any way.

"Part of my concern with the overall structure of the death review committee and the government oversight of that committee is that the monitoring and implementation of the recommendations is not what it could be," Koshan said.

Accountability from the government is crucial for the committee's work to have meaning, she said.

"The Family Violence Death Review Committee is only going to be effective if the government takes its recommendations seriously," she said, adding she believes the committee should report directly to the legislature.

Perhaps the committee's most specific recommendation in the 2012 case was that the province create a public awareness campaign about domestic violence and where to seek help, in what appeared to be a direct response to a major finding from the report.

Many people knew the perpetrator — who had mental-health issues and, reportedly, a history of childhood abuse — was abusive toward his partners. Some even knew the "severity and regularity" of that abuse. But few intervened or reported him to authorities.

"Further still, several individuals later reported having seen or heard substantial evidence to suggest that the perpetrator had either grievously injured or killed the victim, yet did nothing because they 'didn't want to know,'" the committee's review found.

In her statement, Sawhney's press secretary did not address the issue of why the government did not publicize the two case reports when they were released in July 2019, or respond publicly to the committee's recommendations.

Community and Social Services has requested responses from all affected ministries by the end of this month and the responses will be posted shortly after, she said.

Case reports often quietly released

The committee submits its reports to Alberta's community and social services minister, who decides how and when to publicly release them. But over the years, most of the reports have been released with no accompanying media announcements.

Instead, they are simply posted on a government website — one Reimer said her organization must keep checking to see if new case reports are available.

"Ideally, we would be brought in, and (we and) other domestic violence service providers would be given copies of the report," she said. "And then we could also participate in looking at how to have that accountability built into it, because we're the eyes in the community."

The statement from Minister Sawhney's press secretary did not address the criticism about how the reports are released.

Often, the reports come out several years after the deaths being investigated.

In late December 2014, Edmonton man Phu Lam killed eight people, including his wife Thuy Tien Truong, her young son and niece, several other relatives, and a family friend. Lam then killed himself.

Just days later, the committee announced it would make its review of the case an "absolute priority" and would start its work as soon as police and the medical examiner completed their investigations.

More than five years later, that report still has not been released. An EPS spokesperson confirmed police formally finished their investigation in 2017.

Benson said it took the committee more than a year to receive the full police file, which included forensic reporting and DNA evidence. He said the number of deaths involved meant the review took longer. The committee is currently writing its case report.

"Immediacy is very important when we are talking about family violence issues, again not just in individual cases but really the need to look at these systemically," Koshan said. "What are the failings of our justice system and the different components of our legal system that we should be talking about to try to prevent these deaths?"

She said while the committee's annual reports reveal that women make up the overwhelming majority of victims, it should include more demographic information so the public can see who is most affected by domestic violence.

Reimer said the provincial government and the committee must develop a dissemination strategy for the reports, one that establishes timelines for action.

"When are people going to report back on those recommendations, what's going to happen with them," she said. "What are people going to do differently, because we can't keep doing what we have been doing.

"Fatality inquiries, death review committees, they all have made the same recommendations," Reimer continued. "The challenge is to get something done."

If you need help and are in immediate danger, call 911. To find assistance in your area, visit sheltersafe.ca or http://endingviolencecanada.org/getting-help.