Who is Reza Zarrab? Turkish-Iranian gold trader may be working with Mueller investigation of Michael Flynn

Reza Zarrab was arrested in the U.S. in 2016

The mystery of Reza Zarrab may be unraveling.

The Turkish-Iranian businessman has been in a U.S. prison since 2016, but last week, reports emerged that he had been moved and is talking to U.S. special prosecutor Robert Mueller about former U.S. national security advisor Michael Flynn.

Now, it appears Zarrab's name has been removed from court documents in the criminal case against him.

So the big question is: Does Zarrab have details that could prove Flynn was helping foreign countries meddle in U.S. affairs?

The case is also gnawing at the Turkish government. And in a country where conspiracy theories are essentially a default setting, the facts and whispers in the Zarrab case are spinning an extraordinarily wide, sticky web that threatens Ankara and Washington.

Who is Reza Zarrab?

Zarrab is a 34-year-old multi-millionaire gold trader who was picked up in Miami in March 2016 on charges of money laundering and violating U.S. sanctions on Iran.

Just weeks from his trial date, Zarrab was suddenly moved out of prison, fuelling speculation Zarrab has been drawn into Mueller's Russia investigation and may be spilling secrets to save himself.

- 'Ludicrous': Turkey denies report of plan to kidnap Fethullah Gulen from U.S.

- White House says it didn't know Michael Flynn lobbied for Turkey last year

The Flynn connection

NBC is reporting Flynn may have also been negotiating the release of Zarrab himself.

Flynn and his son, Michael, Jr., were doing business for the Turkish government through their consulting firm Intel Group. U.S. President Donald Trump appointed the elder Flynn national security advisor in January.

Flynn lasted less than a month in that job, after the administration learned he wasn't up front about his meetings with a Russian official. Flynn later admitted to being paid to lobby for the Turkish government before entering office, and is now a key figure in the Mueller investigation into whether Russia meddled in the 2016 U.S. election.

The charges against Zarrab

Zarrab and eight others are accused of bribery, money laundering and conspiring to violate U.S. sanctions against Iran. Zarrab is alleged to have facilitated deals between Turkey and Iran to trade gold for gas.

The allegations also implicate the Turkish government.

"Some officials received bribes worth tens of millions of dollars," the indictment reads, and alleges aid shipments to Iran — including firefighting equipment — were used as a cover to obscure the cash that Zarrab was transferring.

The indictment also mentions discussions about a transfer of nearly a million dollars to Canada through Mapna Group, a major Iranian construction and energy company.

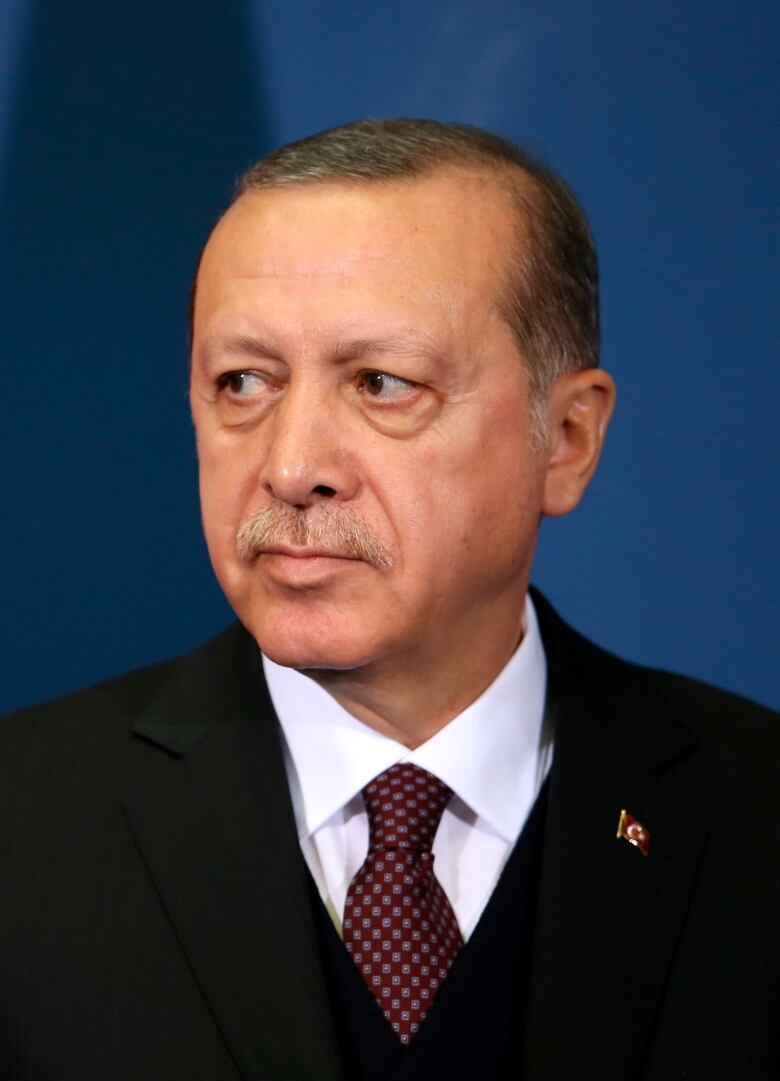

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan is not among the nine people charged, but the indictment does include a former government minister and the head of a bank the government owns a majority stake in.

"This is a huge deal," said Gonul Tol, the founding director of the Middle East Institute's Center for Turkish Studies in Washington. She said there are even more personal pressure points for Erdogan.

"What is most worrying to Erdogan is his family is involved in this," Tol said. U.S. court documents reportedly reveal Zarrab donated millions of dollars to a charity run by Erdogan's wife, Emine.

Zarrab's ties to Turkey

Zarrab was infamous in Turkey long before his arrest in Miami in March 2016. His exorbitant shopping sprees with his wife, Turkish pop star Ebru Gundes, made him a tabloid star. (She is now divorcing him.)

His dealings with Erdogan and his closest allies made Zarrab, like the government itself, seemingly untouchable. Back in 2013, Zarrab and the government were entangled in allegations that mirrored the ones now before a U.S. court: corruption, bribery, money laundering.

There were reports of shoeboxes stuffed with cash and stashed away and a plane full of gold stopped by Turkish authorities, only to be allowed through after a minister was allegedly bribed. The scandal resulted in political resignations and hit Erdogan's AK Party in the 2014 elections, but the president survived the crisis.

Erdogan and pro-government media blamed Fethullah Gulen and his followers for the allegations.

Atilla Yesilada, a political analyst based in Istanbul, called Gulen's followers "a real menace, out to get Turkey," but said these U.S. charges can't be easily brushed aside.

"Whether this violates American sanctions is the issue here," Yesilada said. "Turkey cannot claim that Zarrab was falsely accused."

A national obsession

Turks are transfixed by the case and what it might mean. Many watching the case believe Zarrab flew to the U.S. in 2016 knowing he would be arrested.

"Zarrab received information an Iranian hit team was after him, to assassinate him, and he didn't think Turkish police was going to do a good job to protect his life," Yesilada said. "So he chose prison in the United States." Zarrab's partner, Babak Zanjani, is currently facing a death sentence in Iran.

Wild rumours lit up phones across Turkey as news of Zarrab's possible deal with Mueller broke, including that the businessman would be getting a new identity — even a face transplant — to protect him from Iranian assassins.

The Turkish government is doing damage control, as well as fighting back. On Saturday, a Turkish prosecutor announced he is investigating Preet Bharara and Joon H. Kim, the two lawyers who prepared the indictments against Zarrab. Bharara is the former U.S. Attorney for New York and Kim is his acting successor.

In a rare move, Turkish officials sent a memo to their U.S. counterparts last week, demanding to know where Zarrab is and if he is in good health. Turkey's foreign minister later said U.S. officials responded, saying he was moved elsewhere, and doing well.

This case, and Turkey's demands that the U.S. extradite Gulen, are behind a series of diplomatic disputes between these NATO allies. In May, there was violence outside the Turkish embassy in Washington, where Erdogan's guards fought with protesters. A grand jury in the U.S. has issued indictments for 19 people involved in that melee.

Several U.S. consular officials have been detained in Turkey, sparking a visa crisis between the two countries.

Erdogan accuses the U.S. prosecutors of having "ulterior motives" in pushing the Zarrab case, insinuating it is part of a larger threat to harm his government. On Monday, one of Turkey's deputy prime ministers called the case "a conspiracy aimed at Turkey," and compared the suspects to "hostages."

Yesilada doesn't think the U.S. or EU "have any interest in weakening Turkey," he said. "Turkey remains the garrison of stability in this region."

But the deepening fractures between Turkey and the US are threatening that stability.

"Things are getting worse and they're nowhere close to a resolution," Tol said. "I don't see a way out of this crisis."