In Ukraine war, neither side is winning. Is it time to negotiate?

Russia and Ukraine both reluctant to cede territory, but some Western allies are losing patience

A month in, Ukraine's spring counteroffensive is struggling against entrenched Russian forces and appears to have entered a near-frozen state, where neither side is making significant ground gains. That's renewing debate about whether now is the time to negotiate an end to the conflict.

The idea of an armistice is controversial because many experts don't believe Russian President Vladimir Putin will ever give up his ambition to control all of Ukraine and could never be trusted.

"Russia will break any agreement that it makes," said Ian Garner, an adjunct assistant professor of political studies at Queen's University in Kingston, Ont., who has analyzed Russian war propaganda.

"The history of negotiating with Vladimir Putin for the past 22 years has been a history of broken promises. The Russian state is brutally corrupt, increasingly attached to militarism and increasingly untrustworthy."

Still, the argument fills the pages of the respected Foreign Affairs magazine, where dueling headlines proclaim the conflict in Ukraine is an "Unwinnable War" and negotiations are the only realistic endgame, countered by the claim that "Russia Can Only Be Stopped On The Battlefield."

Talk now or hold out for more gains

Wars are nearly always ended at a negotiating table, so the debate is really about timing: Should the two sides enter into talks now or wait, each gambling on the belief that they can take more ground and be in a stronger position to negotiate later?

"This is not an either-or situation," said retired U.S. colonel Mark F. Cancian. "A negotiated settlement will reflect the situation on the battlefield. Even if one side achieves a decisive win, the negotiations will codify that situation."

Russia's military campaign is going nowhere, but Putin may well believe he can wait out the West's support of Ukraine in a war of attrition.

Republicans in the U.S. Congress have grown impatient with the expensive transfers of weapons. Donald Trump, who has shown friendliness toward Russia in the past and is again running for president in 2024 shares similar views.

Next year's presidential and congressional elections in the U.S. could fundamentally alter the West's support for Ukraine's defence.

Some Western European politicians have also quietly nudged Ukrainian officials toward talks this year, especially since neither side has gained much ground in the last nine months, and Ukraine's current action is sputtering.

"We will know in about another month when the results of the Ukrainian counteroffensive become clear," said Cancian of the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, D.C. "So far, progress has been disappointing, steady but slow."

Kilometres of trenches have staved off counteroffensive

Warning: This section contains an image of a dead body

Of course, Russia's army is hardly in great shape.

Its spring offensive cost tens of thousands of Russian lives, with little to show for it beyond the symbolic win at Bakhmut – which Ukrainian forces have since successfully chipped away at with their own counteroffensive.

Russian forces are exhausted, senior commanders are being replaced for insubordination, following a mutiny by the head of the Wagner mercenary group.

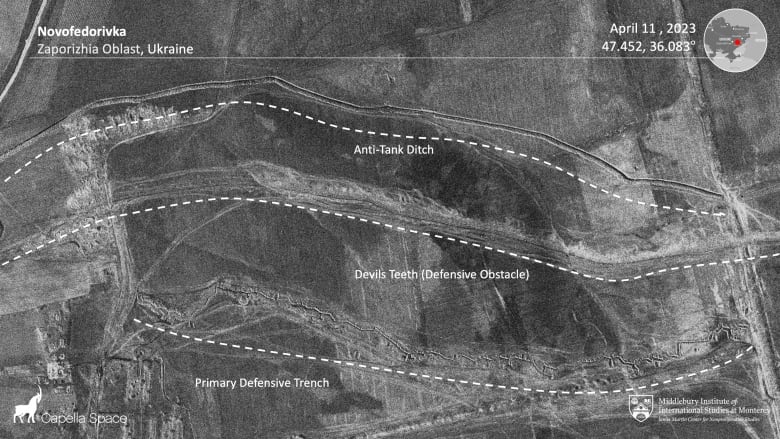

Western assessments suggest the Kremlin has lost so many soldiers and equipment, it would be unable to launch another offensive this year. But Russia did use the winter to build hundreds of kilometres of trenches, tank ditches and other defences, which have so far kept Ukraine from finding a weak spot in the Russian frontline through which to pour thousands of their own Western-equipped soldiers.

"They have extensive entrenchments," said Michael Kofman, one of the top U.S. analysts on Russia's armed forces, on his War on the Rocks podcast.

"They're digging fresh trenches every day and putting down more mines … the challenge is significant, to put it mildly."

There is no question Ukraine has also lost significant equipment and personnel. Accurate figures are a closely guarded secret, but certainly thousands of soldiers have been killed while tanks, artillery guns and infantry fighting vehicles have been destroyed.

"War is not like it is in the movies," Kofman said. "War is messy. It's ugly. And you aren't going to see images of hundreds of [Ukrainian] tanks crossing Russian lines."

Could Korean War type ceasefire work in Ukraine?

In short, it's a stalemate.

And the world has seen one like it before.

Between 1950 and 1953, on the Korean peninsula, South Korea (backed by the United States) and North Korea (backed by China and the Soviet Union) saw horrific battles that cost an estimated three million lives.

That conflict began when the North invaded and seized the capital of the south, Seoul.

In the months that followed, foreign nations inserted weapons and provided training. Land was fought over, in an ever-looping sequence of winning and losing.

Then, as now, neither side was particularly interested in a negotiated end, in spite of the military stalemate.

"It was only with Stalin's death in March 1953 that Soviet leaders reconsidered the whole misadventure and prodded their allies toward an agreement," Cold War historian Sergey Radchenko wrote in the New York Times on the one-year anniversary of the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

While an armistice was struck that year, the war itself has never officially ended. The fighting has just been suspended for seven decades.

It's far from peace. North Korea today is a menace to its neighbour and the world but now is armed with nuclear weapons.

Its leader, Kim Jong Un, is grandson to Kim Il Sung, who led North Korea when the ceasefire was signed in 1953.

And that, says Walter Dorn, professor of defence studies at the Royal Military College of Canada in Kingston, is where comparisons to Russia take a different path.

"Vladimir Putin does not have a line of succession like Kim Il Sung had," he said. "His eventual replacement as Russian president won't have a family dynasty to continue."

Neither side showing signs of backing down on borders

Dorn predicts the Ukraine war to end by negotiation, with a heavily militarized border. The issue is where that border will be.

Ukraine wants Russia to relinquish all land that it invaded as far back as 2014, including Crimea. Russia would want to keep at least what it now controls to be able to claim some kind of victory.

Those are vastly different starting positions – reflecting thousands of square kilometres of territory.

"The two sides are so far apart," said Garner. "The Ukrainians are not tiring of the war and [not] willing to compromise just to get it over with … On the Russian side, there is no sign that they will back down."

Put simply, neither side wants to negotiate.

That may change in the last half of this year when the Ukrainian offensive concludes, and both sides will assess their likelihood of future success.

If some kind of deal could be struck – or at least an agreement to stop fighting – who would want to commit troops to keep the two sides apart?

One suggestion is a peacekeeping force. Dorn expects that job would fall to India. With some political alignment to Russia (it buys the largest amount of Russia gas now), India could be palatable to Putin and is already the largest contributor of forces to peacekeeping missions, so may be acceptable to the West.

Still, Ukraine would want to defend its own borders.

The G7 recently made significant financial and military commitments to keep Ukraine armed and able to defend itself even after the conflict ends, however it may end.

This is sometimes called the porcupine approach, ensuring Ukraine has enough muscle to stop a re-invasion once Russia has had the time to re-arm and recruit more soldiers.

Israel operates a similar strategy at its borders, though it also has nuclear weapons as a strategic deterrent.

Ukraine once had the third-largest nuclear weapons stockpile in the world but relinquished them in a 1994 agreement in return for a pledge by Russia, the United Kingdom and the United States to respect its independence, sovereignty and existing borders.

Putin has broken Russia's end of that deal. Repeatedly.

So, can he be trusted now?

During a 2008 visit, he told U.S. President George W. Bush that "Ukraine is not a real country." In 2021, he argued Ukrainian nationality did not exist. The next year, he sent a mass invasion force to seize Kyiv.

It didn't work. And Ukrainian leaders aren't particularly interested in giving him another opportunity.