'Jim Crow's last stand': How a heated governor's race in the South became a crusade for voting rights

Registration of 53,000 mostly black voters placed on 'pending' list amid cries of voter suppression

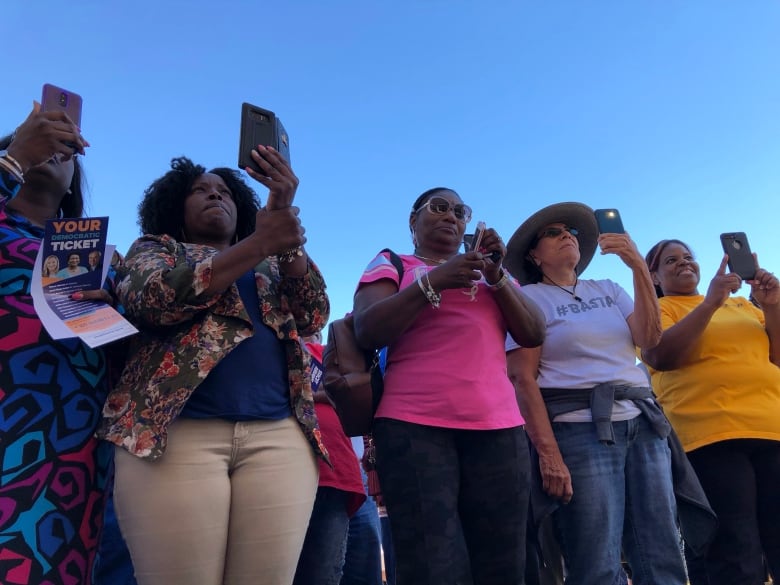

Under a cloudless sky in a former cotton-milling town outside Atlanta's city limits, Stacey Abrams, the Democratic nominee for governor of Georgia, led a stirring call-and-response chant commanding a massive voter turnout.

"You're gonna do what?" she roared.

"Vote early!" the crowd answered.

"And then you're gonna what?"

"Volunteer hard!" they shouted back.

"Because this is our voice!"

"Our voices!"

Cheers erupted from the crowd of about 150. Abrams bounded off the stage. The soulful vocals of Andra Day's Rise Up drifted from speakers on a gazebo, and a crowd of predominantly black devotees rushed to fill out canvassing sign-up sheets on the trunk of a parked Ford Crown Vic.

It would have been easy to dismiss Abrams's get-out-the-vote stumping last Thursday as boilerplate. But the call for early voting isn't just a canned line here. Not in the Deep South, anyway, where systemic racism historically kept black people away from the polls, and where the current hotly contested governor's race is being gripped by recent complaints of voter suppression affecting tens of thousands of minorities.

The controversy in Georgia stems mostly from a rule that assigns a "pending" status to voter registrations that have the slightest discrepancy with a state driver's licence database or a social security database.

Any mismatch with voter registration forms — a dropped hyphen, accent, a transposed digit or a maiden name in place of a married name — could render someone's voting status frozen under an "Exact Match" standard.

"Because of that, 53,000 voters are in limbo," Abrams told CBC News on the sidelines of the rally in Griffin.

"This has had a disproportionate effect on voters of colour and women ... and it's part of a pattern of suppression."

Voters have 26 months to fix any errors before their applications are cancelled and their names removed from the rolls. Voting rights advocates say that task can be a daunting bureaucratic challenge for many affected voters.

If she wins her neck-and-neck race against Republican Brian Kemp, Abrams will be the first black female governor in an increasingly racially diverse "New South." But her supporters say it's the Old South that's standing in the way of her making history.

Last Monday, the same day early voting began, about 40 seniors boarded a bus at a voter outreach event to go to a Jefferson County polling station. But the bus, organized by a group called the Black Voters Matters Fund and emblazoned with the words "The South Is Rising," never departed the seniors centre. According to the group, someone from the county registrar's office saw the parked bus and called to complain, and county officials put a stop to the trip.

Yesterday, we experienced voter suppression in Louisville, Georgia. <br>We had a whole busload of beautiful black elders ready to go vote when the County Commissioner shut us down and made our elders get off the bus without having the chance to vote. Share this to spread the word! <a href="https://t.co/fvULloAz4J">pic.twitter.com/fvULloAz4J</a>

—@BlackVotersMtrThe seniors had been singing the spiritual Ain't Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me Around when Cliff Albright, a co-founder of the Black Voters Matter Fund, boarded the bus with a grim expression.

"He told them he had bad news," said LaTosha Brown, a fellow co-founder. "Almost immediately, a senior in the back said, 'We can't vote.' It's like they're already expecting to be stopped. You don't even have to go back to the 1960s."

In a statement to local media, the county said officials were "uncomfortable" with patrons of the facility departing on a bus "with an unknown third party." The county also cited the "long-standing practice" of prohibiting political activities during business hours. Black Voters Matter Fund is a nonpartisan group and its leadership said nobody was encouraged to vote for a particular party or candidate.

'Jelly bean test'

In August, board of election officials in predominantly black Randolph County closed more than three-quarters of their polling locations, including one that serves a community that is 97 per cent black.

Seniors interviewed at advance polling stations in Cobb County and Spalding County said the "pending" list of 53,000 voters was but another reminder of the old Jim Crow laws that enforced racial segregation taking on more sophisticated forms.

Rosalyn Payne, 72, grew up down the street from the park where Abrams held her rally in Griffin. She recalls stories from her mother and grandmother about the indignities of the "jelly bean test." Registrars would challenge black voters to guess the number of jelly beans in a jar to gauge their fitness to vote.

"You had to know the Constitution. Or sometimes you had to count marbles in a jar. You didn't know the answer, you couldn't vote," she said.

"Now, it's if you don't have the 'L' or you don't have the period in your name, you're put on the purge list. It's counting marbles 2018."

Abrams is in a dead heat with Kemp, Georgia's secretary of state. The margins are tight enough that 50,000 votes could tip the balance.

And there's another wrinkle: As secretary of state, Kemp is effectively overseeing his own election race. His office is in charge of enforcing the "Exact Match" law and election rules, and Kemp has refused to resign amid accusations of a conflict of interest.

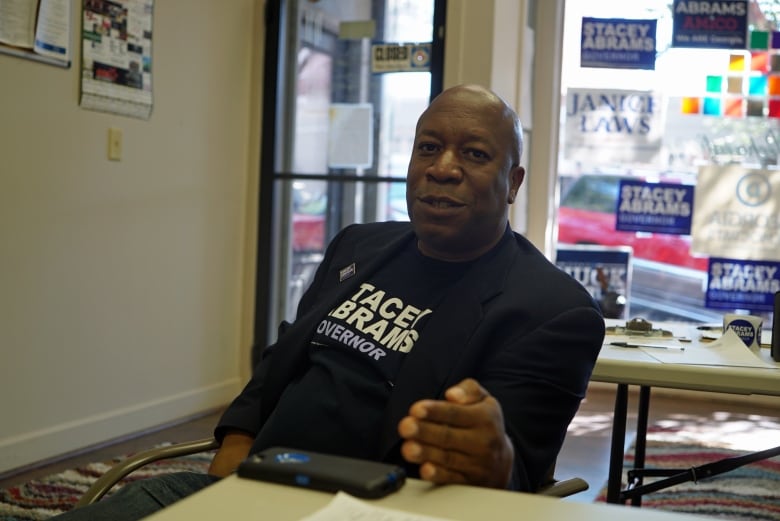

"Let me put it to you this way: If you're the hawk and you're eating chickens for breakfast, should you be watching the chickens?" asked Carleyl Shackleton, a field office manager for the Abrams campaign in Spalding County.

'Aggressive throwbacks'

An Associated Press analysis of the names on the "pending" list found nearly 70 per cent of the people listed were black.

"I think that in a lot of ways, this feels like Jim Crow's last stand," said Nse Ufot, executive director of the New Georgia Project, one of the groups suing Kemp, claiming his office has thrown the voting rights of tens of thousands into jeopardy. The voter-registration organization was founded by Abrams.

"We're seeing really aggressive throwbacks to pre-Civil Rights Act, pre-Voting Rights Act Georgia, as people are grasping for straws and grappling with impending changes here in the State of Georgia," Ufot said.

Demographic data projects that in the next six years, Georgia will be the first state in the Deep South with a white minority, as the black, Asian and Latino communities continue to grow.

"It is the New South, there's no question about that," Ufot said.

Kemp's office did not respond to requests for comment. He has said the issue is a "manufactured" scandal, and points out the 53,000 Georgians can still cast provisional ballots and vote, provided they show up with appropriate ID, which is required by the state. His defenders say he is simply executing the law.

His campaign spokesperson, Ryan Mahoney, issued a statement saying "Kemp is fighting to protect the integrity of our elections and ensure that only legal citizens cast a ballot."

Conservatives have long argued ID requirements at the polls prevent voter fraud, but wide-scale voter fraud in the U.S. has been proven to be a myth.

On the other hand, studies show requirements for specific photo ID present bureaucratic and financial hurdles that disproportionately impact poor and black voters who want to participate in democracy.

CBC News spoke with four voters who went public with their stories after discovering they were placed on the "pending" list. Each voted as recently as the 2016 presidential election, and each could only guess what their mismatch was.

Marsha Appling-Nunez wondered if it had to do with the hyphen in "Appling-Nunez." But when she was shown an Excel sheet of pending voters earlier this month, she noticed the "A" in Appling was missing next to her name and contact information. She chalks it up to a clerical error by the registrar.

"Not your average corn-fed name," she said.

The adjunct college instructor only learned about her pending status "by fluke" last month, when she attempted to show her students how to register themselves.

Her web browser history shows she tried to re-register through the secretary of state's website at least 45 times between mid-September and Oct. 9.

Sheila Pettiford, a grandmother in east Atlanta, figures she made the list because her first name was entered as "Shelia" on her Georgia driver's licence a few years ago, a typo on her birth certificate that she never corrected.

"When I heard about the purge list, I checked," she said. "I was shocked."

Appling-Nunez and Pettiford are the lucky ones. Screengrabs they saved of the secretary of state's voter eligibility web page showed they had successfully re-registered either on or one day before Oct. 9 — the cut-off date to be eligible to vote on Nov. 6.

It's unlikely that many of the 53,000 listed individuals will know they have a pending status until they try to cast a ballot on election day.

In the meantime, Abrams's call for high voter turnout appears to be working. As of Sunday, over 500,000 people cast ballots in advanced voting — more than tripling the turnout in the same period in 2014.