Iceland: Grappling with a frozen economy

Shock, polite protest and some hope mark the end of island's boom

Iceland's police, it's sometimes affectionately said, have so little crime to chase, they're known to take second jobs.

Walking the beat here certainly has its benign moments. When was the last time you saw two uniformed cops gently and genuinely blow kisses at protesters, only to have the protesters wave back with enthusiasm?

It's a nice pause at an ugly time. The protesters were out in Reykjavik, just outside parliament, because the nation is virtually bankrupt.

The currency has crashed, and a third of all Icelanders seem to have lost their savings to the global credit freeze, which exposed Iceland's banks as wildly overextended. Those banks accumulated debts roughly eight times the size of the whole country's economy. In the end, they were too big to bail out.

Warning signs, many say, were ignored by those in charge of the nation and its finances. "Stay calm while we rob you," said one of the posters at that exceedingly polite protest. How long will these people stay polite about their losses?

Nervous leaders beef up security

Certainly that's something the government of Prime Minister Geir Haarde seems to wonder. The normally accessible prime minister is, for the first time, moving about the capital with a security detail. They followed him right up to the podium at a hastily arranged news conference this week.

"Looking back, it would have perhaps been wise to have tightened the framework, but also the bankers themselves probably should have been more careful," Haarde said in response to questions about why he didn't know there was trouble and why he didn't act faster.

He's not the only one being blamed and certainly not the only one who seems nervous now. The governor of the central bank, former prime minister David Oddsson, who is a real target of scorn, now has guards in his neighbourhood.

On streets that are starting to lose the vibrancy of shoppers and partiers, talk isn't of revolution. People still seem to be in shock and tiring of all the rumours and shifting rules.

Will gas, food be available?

A few Canadians who moved to Iceland in the good times, and have built lives and families here, gathered to talk this week in a Reykjavik living room about how their new homeland is shifting before them.

"Productivity has gone way down," said Tara Flynn, "because it's really hard to concentrate when the money you're making isn't worth anything."

They say they're apprehensive to use credit cards abroad and wonder whether the cards will even be accepted.

Ian McAdam said he tried to withdraw Canadian funds from an account he thought was secure and was limited to just $500. "What does all this mean for the rest of the economy?" he asks. "We don't really know.

"Icelanders are wondering how it's going to trickle down, to the point where people are asking, 'Are we going to have gas or food in two weeks' time?' because there's no foreign currency exchange."

Silver lining in the new normal

The recent days of easy credit here are likely gone. Some Icelanders may miss them terribly. People talk of the money flowing, the restaurants and new cars and second mortgages taken used to fund trips abroad.

Depending on what sort of ultimate rescue awaits this nation, the future could be one of living a simpler, more restricted life.

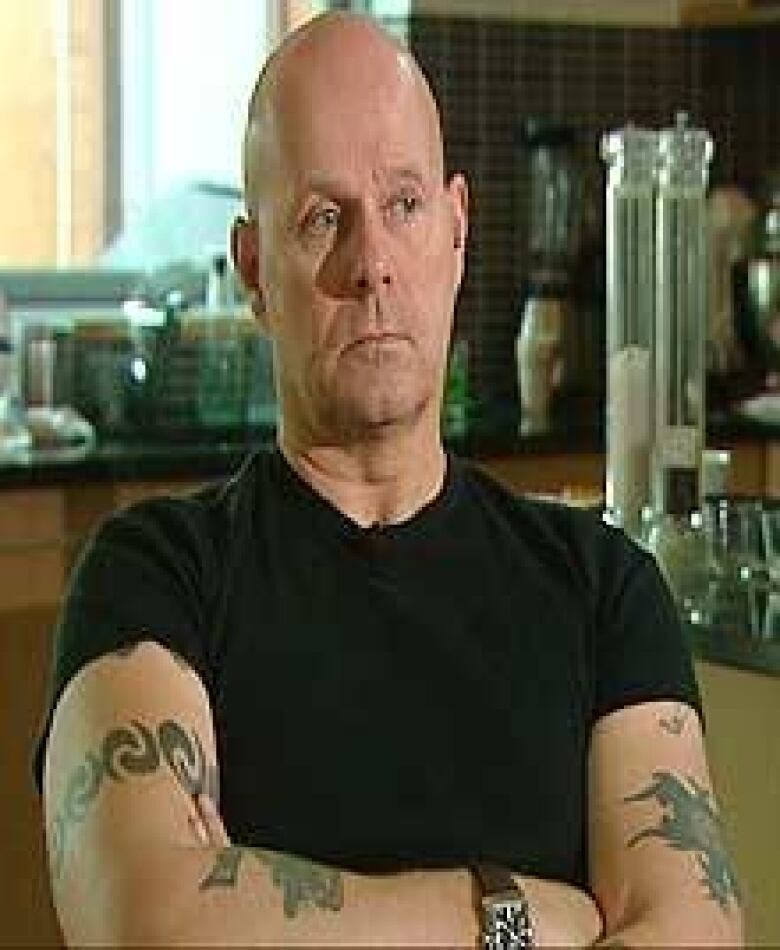

Not everyone here considers that a bad thing. Icelandic rock star Bubbi Morthens is struggling along with his compatriots. He says he lost his savings and wonders whether he'll lose the house he so proudly built.

Curiously, he thinks he might eventually be better off as a result of the jolt the economy gave him. He figures that goes for the country, too.

"It was like a sick body and now we are healing and, because the banks collapsed, things will go back to basics and life will be normal again. Iceland wasn't normal one or two years ago."

Tiny, isolated Iceland might have been the first to fall, but that also may make it the first to re-evaluate day-to-day life in the darkening world of frozen credit.