Some defy mandatory evacuation order despite looming threat of Hurricane Florence

More than 1.7 million people in the Carolinas and Virginia warned to clear out

Anita Harrell says the challenge of gathering up and transporting eight pets means she'll be ignoring the mandatory evacuation order issued to the residents of Wilmington, N.C., as powerful Hurricane Florence threatens to wreak havoc on the state.

"We have four dogs and four cats. And you know, they're just as much as part of my family as anything," Harrell told CBC News in a phone interview. "So we've just decided to secure the house — boarded the windows and boarded up my business — and get everything we need to stay around."

"I don't feel like my life is in danger," she said. "But if I felt like my life was in danger, I would definitely leave."

The U.S. National Hurricane Center is predicting that Florence will blow ashore on Thursday or Friday around the border between North Carolina and South Carolina.

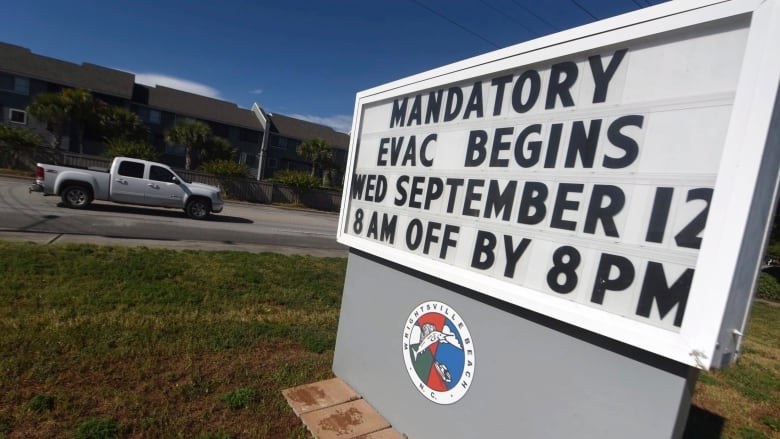

As of Tuesday, more than 1.7 million people in the Carolinas and Virginia were warned to clear out. North Carolina's governor issued what he called a first-of-its-kind mandatory evacuation order for the state's fragile barrier islands, stretching along the coast, from one end to the other.

But some people, like Harrell, are staying put, hoping to weather out the storm.

"The majority of my neighbours are staying," she said. "And we're protecting our homes, we're protecting our families as best we can."

Some of her concerns are allayed by the fact that her home, which she shares with her wife and niece, is above sea level and is not located on the beach. Harrell's fitness business is also located on higher ground, where she said they could flee to if it's no longer safe in their home.

Ahead of the storm, they've boarded up windows, brought in all the outside furniture, and stocked up on supplies, including water, canned goods, plywood and a generator, Harrell said.

Part of the reluctance to leave, she said, is the difficulty of returning once the storm has passed.

"A couple hurricanes ago, I had friends that were stuck out of town for up to two weeks," she said. "They couldn't even get back into town because the roads were wiped out from the rivers. I'd like to be here, too, when it's over.

"So it's not just about the storm, but it's about what's happening after the storm."

'One road in, one road out'

At the Frisco Rod & Gun shop in Frisco, N.C., on the Outer Banks, Brandon Molenda said he's also concerned about the time it would take to return home if he evacuated the area.

"If it does wash the road out — one road in, one road out — it could be two weeks before we get back to our houses," he said. "We don't believe the storm is going to be that bad of a problem."

Molenda said he's been through all the big storms, including Matthew, Irene and Sandy, and many of the local businesses are boarding up, getting the storm shutters down, and moving vehicles to higher ground.

"People down here are very used to this situation — they go through it every year," he said. "They know exactly what to do, what to look for. They know exactly how it's going to play out from previous instances of what has happened in the past."

But part of the problem is that no two hurricanes are ever the same, says Laura Myers, director and senior research scientist at the University of Alabama's Center for Advanced Public Safety.

"If somebody has experienced one, they think they can handle it, and there's never another one that's going to be like the one that they experienced before," said Myers, who studies weather warnings and people's responses.

"These people are also very experienced with coastal events. They don't fear coastal events like they really should, because they've weathered them. And so a lot of them think they can handle it."

After Hurricane Katrina, the families of some of the victims said many stayed because they had survived other storms.

"Because it was such a unique situation, they weren't prepared for it," Myers said. "And that's why they ended up dying from it."

There are likely also some who have heeded evacuation orders for past storms — only to learn that those who stayed had no major problems, she said.

"Then they're less likely to evacuate next time — and that's a real common thing, especially on the East Coast."

Worries about resources

Leaving can pose many challenges, including the transportation of pets. Farmers may also choose to stay to protect their livestock. Medical issues may prompt other individuals to ignore evacuation orders.

"They're going to need their medicine, they're going to need oxygen. The people they're trying to move may be too feeble to move," Myers said. "All of that factors in. And then there's the issue of where are they going to go?

"Do they have a place to go where they know they're going to have the resources they need? And if they don't know that … then they're more likely to say, 'I'm safer at home, regardless of the risk.'"

Residents of at least three states — New York, North Carolina and California — face being charged with a misdemeanor for ignoring mandatory evacuation orders.

But those are rarely enforced, said Myers. Instead, in practical terms, those who defy such orders and find themselves in peril, risk not being rescued by emergency services.

Officials will go door to door, telling people not to expect them to return for at least 72 hours or until the danger has passed, Myers said.

And some locations have gotten more extreme in their warnings, she said.

"They'll go door to door and tell people it's mandatory. And when people refuse, they will hand them a body tag and say, 'Go ahead and fill out this body tag, and go ahead and attach this to yourself, so we will be able to identify you after.'"

With files from The Associated Press