Executive orders: What they are and how Donald Trump is using them

Even before he formally took over, Trump had his team develop a list of actions to be taken on Day 1

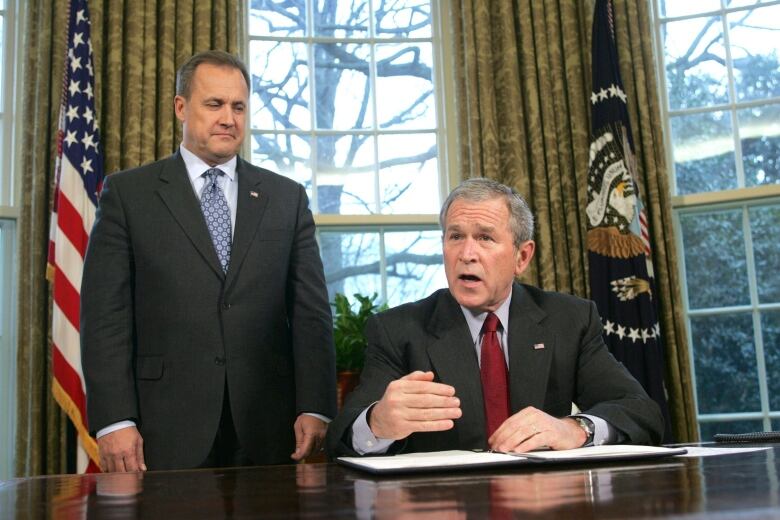

Abraham Lincoln used it to emancipate the slaves. John F. Kennedy used it to start the Peace Corps. George W. Bush used it to limit funding for embryonic stem-cell research.

U.S. President Donald Trump this week used the same unilateral presidential power — the executive order — to direct the "immediate" design and construction of a wall along the southern border with Mexico.

By doing so, he follows a long presidential tradition of bypassing Congress to advance policy agendas.

- Trump to ready executive orders on Mexico wall

- Trump has young, undocumented immigrants living in fear

And although, constitutionally, Trump is obligated to "take care that the laws be faithfully executed," he, like past presidents, will no doubt test the limits of this tool as he moves quickly to enact his campaign promises.

What are executive orders?

They often look like laws, and even carry the force of law. While Congress passes legislation, though, executive orders come from the president. As the country's chief executive, he can set laws into motion.

This gives the president lots of leeway — so much, in fact, that executive orders can take effect even over the objection of Congress. That's where much of the controversy lies, says Ken Mayer, a political science professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

"When the president does have this discretion in carrying out the functions of the office, [his] opponents … will insist that the president is going too far, or acting unconstitutionally," Mayer says.

Barack Obama, for example, was often accused of "executive overreach" by congressional Republicans who said he went beyond the parameters of legitimate executive authority.

Executive orders are more easily overturned than laws, which is why presidents are usually better off enacting their agenda through law.

"When Congress is polarized and incapable of taking action either in favour of or opposition to the president's agenda, though, that's when he has an incentive to exercise unilateral powers," says William Howell, author of Thinking about the Presidency: The Primacy of Power.

What are their limitations?

The danger of "muscling in reforms" via executive orders is that presidents risk creating "a legacy that only stands on clay feet," says Jonathan Turley, who teaches constitutional law at George Washington University in D.C.

There are three ways to challenge executive orders: in the courts, in Congress and via another executive order — all meant to prevent any one president from ruling with abandon.

Another way to overturn the unilateral action is for Congress to pass a law that neutralizes the president's executive order. Such a bill would still require support from two-thirds of the Senate and the House in order to override the president's veto power.

Subsequent presidents also have the power to roll back previous orders using another executive order. "What one president giveth, another can taketh away," Turley says.

- Trump fulfils 'Day 1' vows with 3 executive orders in preview of agenda reset

- Trump issues executive orders to build Mexican border wall, freeze out 'sanctuary' cities

This can result in a pendulum swing of the undoing and reviving of executive orders as administrations change.

When Obama came into office in 2009, for example, he signed an order to restore funding to stem-cell research that his predecessor, Bush, had put an end to during his administration.

Executive orders, however, can't rescind legislation already passed by Congress.

How has Trump used his executive authorities?

Trump campaigned on a promise to "cancel every unconstitutional executive action, memorandum and order issued by President Obama." In his first week in office, he has already taken action to:

- Dismantle the Affordable Care Act;

- Withdraw from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) trade deal;

- Revive the Ronald Reagan-era "Mexico City Policy" that bars the U.S. from funding foreign aid groups that include abortion in their services;

- Institute a hiring freeze for federal government workers.

Only one of these actions — dismantling Obamacare — was laid out under an executive order. The rest were listed as presidential memorandums. (This, despite Trump himself mixing up the nomenclature in his own Facebook post.)

Both are considered executive actions, a catch-all umbrella term that may also include:

- Presidential proclamations;

- National security directives;

- Presidential determinations;

- Policy guidance;

- Policy directives;

- Presidential notices.

Wait — memorandums? What's the difference?

Legally, not much. It boils down to how each action is counted and published in the federal register. Executive orders are numbered as part of their reporting requirements, for example.

"But if you just compare a lot of memoranda and a lot of executive orders, there's not a clear distinction why one is one thing, and the other is the other thing," Howell says.

Both types of executive action still carry the weight of law and the terms are sometimes used interchangeably. (The other, more general actions listed above, on the other hand, do not carry the weight of law.)

On Wednesday, Trump's office issued an executive order to direct construction of a wall along the border with Mexico. He has also signed executive memorandums clearing the way for the Keystone XL and Dakota Access pipeline projects, both of which were halted under Obama.

And Trump has signalled he might issue an order to ban Syrian refugees from entering the U.S.

- Trump alleges millions voted illegally for Clinton

- Trump is wrong about 'millions' of illegal voters

As of Thursday, Trump has signed four executive orders and eight presidential memorandums. According to White House records, this has not outpaced Barack Obama, who signed five orders and 10 memorandums in his first week.

George W. Bush signed his first executive order during his second week in office, as did Bill Clinton.

What will come of Trump's executive orders?

Regarding Trump's push to build the wall — part of an executive order on border security and immigration enforcement — it's not quite as simple as issuing that order.

While the president has some discretion to reprogram small amounts of federal funds, he will need Congress to appropriate the $14 to $20 billion US needed to actually support this construction.

Congress can refuse, in which case it's hard to see how the wall would ever get built.

"Maybe it's more an effort to drive a stake in the ground, metaphorically," Mayer says. "Maybe it's announcing this is the official policy of the United States. Sometimes executive orders are clearly substantive; sometimes they have a symbolic element."

Trump's team also suggests the president will use an executive order to announce his intent to renegotiate or pull out of the North American Free Trade Agreement. The president cannot revoke the statute via an order, but he can use one to give six months' notice about his renegotiation or withdrawal plans.

An executive order on NAFTA, then, would probably look more like a presidential document notifying member nations of these plans.

How have past presidents used executive orders?

The use of executive orders goes back to George Washington.

"When Washington declared the United States would be neutral and avoid foreign entanglements, that was done not through law but a unilateral directive," Howell says.

Although every president since Washington has used executive orders, William Henry Harrison's term was so short he didn't get the chance. He died of pneumonia 31 days after assuming office in 1841.

The term "executive order" wasn't part of the formal language of government until 1862. Lincoln's emancipation proclamation was technically a declaration announcing the policy but is now recognized as an executive order.

More often than not, executive orders are mundane, involving matters of bookkeeping, honouring citizens, establishing special holidays or the reorganization of lines of succession in federal agencies.

Executive orders are used out of necessity more than anything, says John Hudak, a senior fellow in governance studies with the Brookings Institution.

"Congress can't make every minute policy decision, so, at least sometimes, they'll delegate that to the president, so the president needs manoeuvrability," he says.

Other times, they directly impact people's lives. Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 in 1942 to authorize the internment of more than 100,000 people of Japanese ancestry in prison camps. In 2014, Obama signed Executive Order 13658 to raise the minimum wage of federal contractors.

What is Obama's legacy on executive orders?

It has been mistakenly reported that Obama issued more executive orders than any president in modern history.

In fact, he issued 277 executive orders during his eight years in office, an average of 35 a year, according to the Pew Research Foundation. That's fewer than the 36 per year that George W. Bush averaged and the 46 per year of Bill Clinton.

"But you'd be wrong to infer from this that Obama was reticent to use presidential powers," Howell says, as the former president still issued "a lot more memoranda" than past presidents.