These Democrats are trying to help far-right Republicans win their primaries

Democratic strategist calls plan a 'dangerous game'

During the Republican gubernatorial primary in Pennsylvania, a political ad ran against Doug Mastriano, accusing the state senator of wanting to "outlaw abortion," of being "one of Donald Trump's strongest supporters" who "led the fight to audit the 2020 election."

However the ad was not funded by any of the Republican opponents for Mastriano — often labelled a "far-right" conservative —� but by the Democratic nominee for governor, Attorney General Josh Shapiro.

According to some political observers, while it may sound like a typical negative political ad, it's actually not meant to hurt Mastriano's chances against his Republican rivals. Instead, it's meant to boost his profile and conservative credentials to the Republican party base.

It's apparently all part of a Democratic strategy aiming to help those seen as extremist Republican candidates to secure their Republican party's nomination. (Which Mastriano did win.)

The hope for Democrats is that those extreme Republican candidates would be much easier for Democrats to beat in the November general election. But the strategy has raised some concerns about effectiveness and whether it could have unintended consequences.

'Incredibly dangerous game'

Christy Setzer, a Democratic strategist who worked on the campaigns of former vice president Al Gore and former Vermont governor Howard Dean, cautions against it.

"It's a high wire act and an incredibly dangerous game," she said in an email to CBC News.

The difficult part is knowing what messaging makes a candidate too toxic for the GOP primary, she said. The dangerous part is that "it could easily backfire and result in the election of another extremist who's going to try to overturn the next election."

"Democrats should focus on their own primaries, and in the general, on making an effective contrast between our positive story and their insanity."

Yet this strategy appears to be playing out in a handful of races in the U.S.

In Illinois, for example, the state's Democratic Governor J.B. Pritzker along with the Democratic Governor's Association (DGA) have reportedly spent around $34 million US on the Republican primary, according to Politico.

Their aim, apparently, in the governor's race, is stopping Republican Richard Irvin, who would become the first Black governor of Illinois if he would win the general election.

Democrats reportedly fear facing off against Irvin in a general election, so they have launched ads against him that they believe will make him less palatable to Republican primary voters.

One ad launched back in March by the Democratic Governor's Association critiqued Irvin's past work as a defence attorney. But at the same time, in what could be considered some political reverse psychology, the DGA ran adds depicting Irvin's Republican opponent Darren Bailey as "too conservative for Illinois," a message that would actually resonate with the Republican base.

Asked about this apparent strategy to get certain Republicans nominated, spokesperson Christina Amestoy said in an email to CBC News: "The DGA is wasting no time in educating the public about these Republicans."

"These elected officials and formerly elected officials want to deceptively retell their histories and we're just filling in the gaps."

Meanwhile, In Colorado, a Democratic super PAC, or political action committee, called Democratic Colorado has also been accused of meddling in that state's Republican primary. It has reportedly spent more than $1 million airing ads to attack senatorial candidate Joe O'Dea, who has a history of political donations to Democratic candidates, according to the Colorado Springs Gazette.

His Republican opponent, Ron Hanks, whom Democrats seem keener to face in the general election, is also labelled as being "too conservative for Colorado" — a message observers again believe isn't meant to hurt him in the Republican primary, but help his bid with Republican voters.

As well, in California, Democrat-affiliated House Majority PAC has been running ads that seem meant to boost the chances of Republican Chris Mathys, who is also considered a far-right candidate, and who is referred to in the ads as "a true conservative, 100 per cent pro-Trump and proud."

'Vote their hearts, not their heads'

Primaries mostly attract the "wings" of the party, or the party base who are often drawn to more extreme candidates, said Elaine Kamarck, Director of the Center for Effective Public Management at the Brookings Institution.

"In primaries, the voters tend to vote their hearts, not their heads," she said. "That's why extreme candidates, whether on the left or the right, tend to have a pretty decent shot in primaries, even if they're going to lose the general election."

That's also why she believed the Democratic strategy could prove effective in a general election.

"I think generally the crazier the candidate is, the easier they are to be beaten. There is there is still a centre in American politics. It's very small, but it's crucial," Kamarck said.

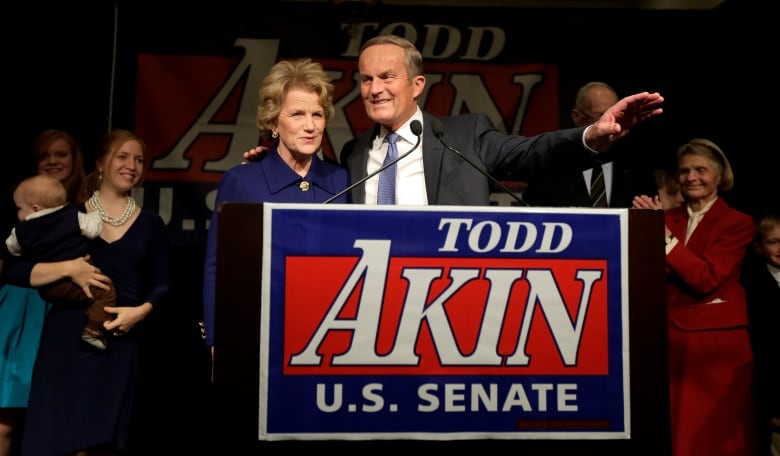

That strategy certainly paid off for former Missouri Senator Claire McCaskill, who has admitted she helped Republican Todd Akin win his primary in 2012 so she could face him.

"I told my team we needed to put Akin's uber-conservative bona fides in an ad — and then, using reverse psychology, tell voters not to vote for him. And we needed to run the hell out of that ad," she wrote back in 2015 for Politico in a piece titled: "How I helped Todd Akin win — so I could beat him later."

But in a recent interview with NPR, McCaskill said there are "certainly risks" with this kind of strategy. She said she now fears there isn't the Republican leadership to stand up to an extremist candidate like there was when she ran against Akin, who died last fall at 74. His campaign was sunk when he was slammed by both parties after he spoke about how "legitimate rape" rarely leads to pregnancy.

'Big expenditure of money'

Democratic strategist Hank Sheinkopf said he believes that with limited financial resources, ads to get certain Republicans elected may not be the best use of campaign money.

"It's an awful awful big expenditure of money when you need to defend [Democratic] candidates," he said.

Sheinkopf said while politics is one thing, so too is a functioning government, and the risk of putting more extreme politicians in office also risks adding more clog.

John Geer, political science professor at Vanderbilt University and author of Defense of Negativity: Attacks Ads in Presidential Campaigns, said the belief that extreme candidates will have a harder time competing in the general election is probably true.

But Geer said in today's political scene in the U.S. it's much more about turnout than it is about conversion of the undecided.

"So if you happen to have an extreme candidate, does that actually give the base a stronger reason to turn out and put into doubt this old long standing approach, the more extreme candidates have a harder time."