'Please God! Let us be out': Portrait of a fishing town's 'Brexit' debate

Emotions running high in British town of Boston ahead of June 23 EU referendum vote

Listen to CBC Radio on Monday night for The World at Six's special report on the Brexit vote and what it could mean for Britain, Europe and Canada.

An impeccably dressed woman in her 70s with carefully turned out hair sits on a sunny terrace not far from the famed tower of St. Botolph's Church in the English town of Boston, making a fervent wish.

"I want to be out. I want, want, want, want — please God! — let us be out."

This is Yvonne Stevens, a local councillor for the U.K. Independence Party or UKIP. Its roots date back to the 1990s and British opposition to the signing of the Maastricht Treaty enshrining key tenets of European integration.

- David Cameron warns against British exit from EU

- Trudeau steps into 'Brexit' debate, says Britain should stay in EU

It's also a party that's played heavily on anti-immigrant sentiment, and immigration is one of the key issues motivating those who want Britain to leave the European Union in a referendum on June 23. Stevens is no exception.

"Let's say, 'No, let's stop,'" says Stevens, referring to unfettered immigration of EU citizens entitled to live and work in any EU country of their choosing.

Over the past decade, Boston has seen the arrival of thousands of EU migrants from eastern Europe and is now home to the largest concentration of Polish immigrants in England and Wales.

Many arrived in the years after Poland joined the EU in 2004 and Polish restaurants, grocery stores and butcher shops have changed the face of the high street.

Stevens says the town doesn't have the schools or health-care services needed to cope with the added numbers. She insists she's not a racist.

"Let's have people coming in who have a specific qualification that we need, not just people that are going to stand around drinking, defecating, urinating in our town and throwing all their rubbish," she says. "I'm not saying English people don't also throw some rubbish, but I think we've been trained a bit more to put our rubbish in the bins."

For the record, we noticed no defecating immigrants during our visit. And the Poles we did meet said they hadn't been faced with unwelcoming attitudes from local residents, although there are clearly tensions between communities.

Critics accuse EU migrants from the east of undercutting wages in the fields and packaging plants where many find employment when they arrive.

- Donald Trump says U.K. 'better off' with 'Brexit' from EU

- Obama faces backlash after warning U.K. against leaving EU

Karol Sokolowski arrived in Boston from Poland six years ago with his wife and son. They've since had a second child born in the U.K. He started out working in a packaging plant and now owns his own business.

If anything, he says, the Polish influx has revived an aging town.

"I hear that before, Boston was quite an old town and people [were old] also. So the town was actually dying. And once people started coming ... Boston started to live. Now it's a little overcrowded a bit."

The towns and villages of the Fens along England's eastern coast have been described as the 'Holy Land of the English.' Stevens, for instance, won't describe herself as European. But she doesn't identify with being British either.

"I'm English. I'm English."

The English fishermen based in Boston who make their living on the seas fed by the estuary known as the Wash say the British government sold them out in the 1970s when it joined what would later become known as the European Union.

Their antipathy towards Brussels and what they see as a complete loss of sovereignty is vehement.

"When they took us into it, we went in to trade and that was all. And now we're ruled by them," says Ken Bagley, chairman of the Boston Fishermen's Association. Now it's all directives from Brussels, he says, adding Westminster wouldn't be as strict when it comes to enforcing quotas.

The fishermen's association is also worried about immigration and changes to their town.

"Our population in our little town has doubled," says vice-chairman Roy Brewster. "Because of Europe. Because of just coming in."

Identity is a major theme running through this referendum debate as Britons struggle to define themselves in a changed world.

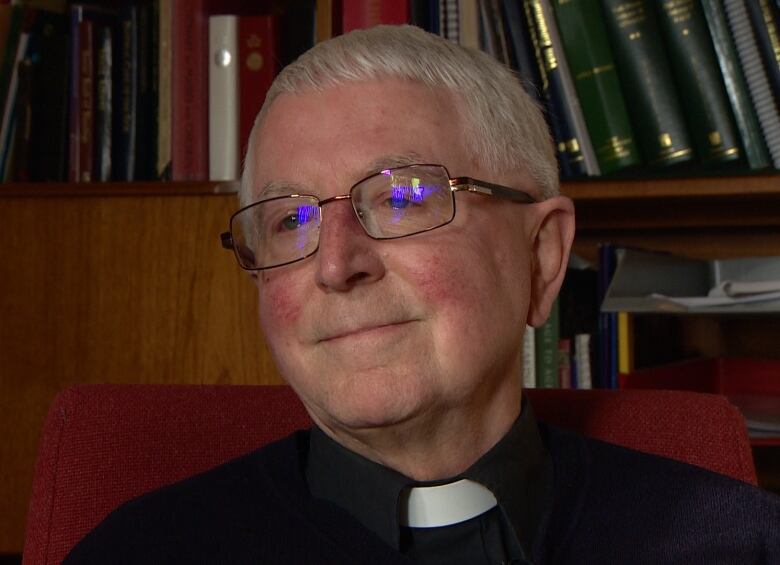

"I think there is a great underlying insecurity from the loss of a sense of identity in post-imperial days," says Father Alex Adkins, a priest at the Catholic Church of St. Mary's in Boston.

"I think that we are in a sense, though we won't admit it, uncertain as to quite who we are and where we fit into the world. And that can generate a good deal of defensiveness."

Adkins says the Polish influx in Boston has rejuvenated the Catholic Church here in the same way Irish immigrants to the town did in the 19th century.

The Church appointed a permanent Polish chaplain three years ago and Polish masses now outnumber those in English. Adkins says true integration will be the work of future generations.

"I think the problem in Boston has been the speed and the quantity. People in a relatively remote Fenland town have felt overwhelmed and to a degree that has been mirrored in our own congregation, though we are welcoming because that's what the Church is about."

Adkins is himself a fervent believer in the European Union and jokes that if the "remain" side loses the referendum, he'll wait for Scotland to become independent with an eye to rejoining the EU and then immigrate so he could still be part of Europe.

"I have always been pro-European by conviction, from the earliest days," he says. "I mean fundamentally I think the time has come for us to move on and explore a new way of being ourselves."

- Britain leaving EU in 'Brexit' a risk to U.K. economy, Mark Carney warns

- British pound sinks on rising 'Brexit' fears

With just one month to go before the vote, opinion polls continue to show a tight race, according to John Curtice, a political scientist and polling expert with the University of Strathclyde.

"Certainly much tighter than the prime minister [David Cameron] ever anticipated," he says.

Curtice describes the typical "leave" voter as "an older person with little, if anything, in the way of educational qualifications." He says the typical "remain" voter is a young person who has been to university.

There are sharp class divisions in the so-called "Brexit" debate, he says.

"There's a real strong social division between a Briton who seems to have lost out from globalization and Britons who seem to be winners. You know it's a debate not unique to Britain. You can see it in the rise of far right parties in Europe, including not least France."

Cleo Anderson is originally from Norfolk, not far from Boston. But she's pursuing a degree in European studies at King's College in London. She fits Curtice's description of the typical "remain" voter and has spent the past few weeks trying to encourage young people to register to vote.

"I would call myself European and I know that I'm unique," she says when asked about who or what she identifies with. "Definitely within my friendship group they often are a bit confused as to why I identify as European. But for me, I kind of feel like it's that one step away from being a world citizen, you know?"

Anderson is working for the "Remain Great, Remain In" camp and says she's not taking anything for granted given her knowledge of parts of the country like Boston.

Her biggest fear is that remain voters are complacent and won't make an effort to vote.

"The assumption is that, 'well of course we'll remain, surely we will.' But I think they're just not paying attention to the polls and seeing how close they are and it is worrying."

The "leave" camp is clearly hoping it will receive a boost from what's known as the "Boris factor", relying on the popularity of the Conservative MP and former London mayor who has been touring the country on his Brexit bus.

"The reason why Boris Johnson is potentially crucial is that [he] has a track record of being able to reach out well beyond the traditional confines of the Conservative party," says John Curtice, although cautioning that Johnson can sometimes "utter the unjudicial word."

"But shall we say that if Boris Johnson had not gone for leave, then the prime minister would have felt rather more confident about the 'remain' side winning given the broader backdrop we have been referring to."