Bastion of tolerance, Sweden opens wide for Syria's refugees

Asylum offer testing Swedes' patience, but forcing Europe to respond

Two years ago, 26-year-old Humam Skaik was moving through the dark streets of a Damascus suburb, trying to avoid Syrian army checkpoints and helping journalists make contact with those who were staging night-time protests against the regime.

Today, he’s wearing a toque and speaking Swedish with impressive fluency. The rumbles he hears on the streets are no longer government tanks, but an army of snowplows.

On the northern fringes of Europe, Sweden has offered its hand to more Syrian refugees than any other Western nation, granting those who make it here permanent residency. And while its generosity has caused some tensions on the home front, including a modest rise in the anti-immigrant right, that has not stopped the Swedish government from lobbying its European counterparts to open their doors as well.

In Skaik's case, he has been living just outside the Swedish city of Norrkoping for 16 months now, having chosen to make his way to Sweden before the government announced its decision in September to offer blanket asylum and permanent residency.

As soon as I left Syria, I felt like, 'OK, I'm safe now' because I didn't care much about where I was going to end up. Just I cared about my soul, my safety...you know?- Humam Skaik, Syrian refugee

"There was not much preparation," he says. “All I thought was to leave.

"As soon as I left Syria I felt like, 'OK, I'm safe now' because I didn’t care much about where I was going to end up. Just I cared about my soul, my safety … you know?”

Skaik decided to leave Syria after he was arrested and tortured for his activism a second time.

He made his own way across the border to Turkey and paid a smuggler 6,000 euros to get him into the European zone, from which you can travel without having to show a passport. He took a train from Austria to Sweden.

A nordic safe haven

For those escaping the chaos that is Syria's civil war, the orderly calm of Sweden’s migrant reception centres is like a soothing balm. When I was there recently, Alaa, who didn't want his full name used and who is also 26, had just arrived at the centre near Stockholm’s Arlanda airport.

He left Damascus a month ago, a city where he says the social fabric has been completely rent by fear and suspicion.

“Because many people have moved out and others have moved in, you have many strangers around you. You don’t recognize everybody in the street. Now it's just strangers’ faces.”

He also points out that "at my age, I could be taken from any checkpoint, maybe to serve in the army. Maybe from one of the other groups for ransom.”

Like Skaik he paid smugglers, but he had a rougher journey. He travelled by boat to Greece where he and others were dumped out by the pilot and forced to swim to shore.

Seeking asylum in the EU

Under EU laws asylum seekers are supposed to make their claims in their first country of entry, and can legally be returned to that country if authorities can prove that’s where they arrived in the EU.

Greece is an exception. Its treatment of asylum seekers has been deemed so dismal that refugees are usually not returned there if they make a claim elsewhere.

Those people who do arrive to the shores of the EU...they have to be looked after. We have to show solidarity, offer them a legally safe asylum procedure.- Tobias Billstrom, Swedish Migration Minister

The majority of the more than two million Syrian refugees forced out by the now almost three-year-old conflict have been given shelter in neighbouring countries: Jordan, Iraq, Turkey and Lebanon.

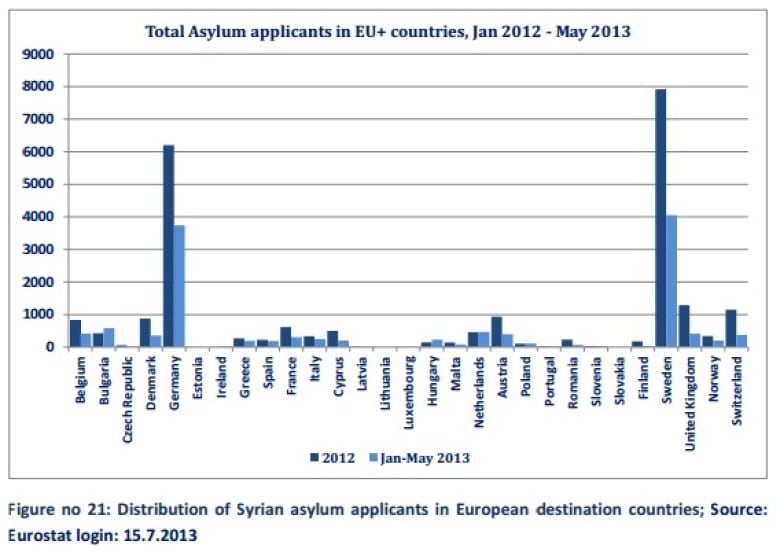

An estimated 50,000 have gone to the EU, most to Sweden and Germany.

Since 2012, Sweden had taken in at least 14,000 Syrian refugees at last count, which is 10 times the 1,300 Canada has promised to absorb over 2013 and 2014.

Sweden’s immigration minister, Tobias Billstrom, says it is not enough for EU countries to simply offer funding to those in the region.

“Those people who do arrive to the shores of the EU," he says, "they have to be looked after. We have to show solidarity, offer them a legally safe asylum procedure.”

Sweden wants more EU countries to sign up to the UN’s resettlement scheme, which it has been operating under for decades now. The UN Human Rights Commission wants members to accept quotas of the most vulnerable refugees for relocation. Under pressure from the Labour opposition, Britain is only now considering joining the scheme.

"But as we can see today we have 13 member states in the European Union who currently operate a quota and some operate very small quotas," says Billstrom. "Fifteen of the 28 member states do not.“

The challenge of integration

Some critics here say the Swedish government’s attitude towards asylum seekers is more liberal than that of the Swedish population, the proof being the modest gains made by an anti-immigrant party in recent years.

Charlotta Waldh teaches Swedish to newcomers in Norrkoping, and she acknowledges there are some integration problems.

We think that everyone has the right to be here, but then we don't really want to mix them with ourselves, do you know what I mean?- Charlotta Waldh, Swedish language teacher

“Swedes are very polite on the surface, but then beneath there is fear from different opinions and strange people that you don’t know all about.”

Waldh says there are contradictions.

“We think that everyone has the right to be here, but then we don’t really want to mix up with them ourselves, do you know what I mean?”

If you peel back the layers in Sweden, you will find communities from just about every one of the world’s main conflicts over past decades: Somalia, Chile, Eritrea, the former-Yugoslavia, Iraq and now Syria.

It’s said that one Swedish town took more Iraqi refugees during the war there than Canada and the United States combined.

“We were reluctant to take refugees in the 1930s, but we did it in the 1940s," says Eskil Wadensjo, an integration expert at Stockholm University.

"Maybe we had a bad conscience. But we also have a long history of people coming from different countries and we are accustomed to it.”

He downplays social problems connected to the increased refugee flows, although he admits there have been pressures lately over jobs and housing.

Hopeful for the future

From the Syrians I met, I didn’t hear a single complaint about their treatment here. All of them were grateful for the welcome they’ve been given.

One young family from the battle-scarred city of Homs left Syria more than a year ago with not a single memento of their former lives, just the clothes on their backs.

Today they live in a small comfortable apartment on the outskirts of Norrkoping, in a mainly immigrant neighbourhood.

“They are providing almost everything,” the father says of the Swedish government. Like many Syrians abroad, they’re still afraid for family back home and prefer not to give their names.

The couple’s two young sons are already in school. “The school system is very good,” says the mother. “They teach in the mother tongue along with Swedish and some English.”

I lived in Syria for 25 years without having papers. But here in Sweden, within three months, I got my first ID. I felt so happy. I felt like a newborn.- Humam Skaik, Syrian refugee

There are, of course, still echoes of the conflict in Syria, even in the muted snow-covered streets of Norrkoping. Pro- and anti-regime Syrians come across each other from time to time.

Humam Skaik says he tries to focus on other things right now, choosing to rebuild a life.

He studies Swedish five days a week in the hopes of becoming a translator and says is grateful for the opportunity.

Born to a Syrian mother and a Palestinian father, he was never given proper Syrian citizenship, even though he was born there.

“I lived in Syria for 25 years without having papers. But here in Sweden within three months, I got my first ID. I felt so happy. I felt like I am newborn.”