Steve Jobs: Misses and hits in a remarkable career

Steve Jobs was widely regarded as a marketing genius with a keen eye for spotting promising technology and trends. But not everything he touched turned instantly to gold.

The Apple chief’s career was pockmarked with challenges. In some instances, it involved things he was working on directly that went awry; in others, he stepped in and gradually fixed the errors made by others.

Above all, it was Jobs’ stubbornness, passion and conviction that made the difference time and again, turning ideas and technology that looked questionable into game-changers.

Apple

Jobs’ best-known miss began and ended as a hit – his leadership of Apple Computer Co. itself.

He founded the company with Steve Wozniak in 1976 and had a string of early successes, starting with the Apple I (a circuit board sold to computer enthusiasts), and the first-ever complete home computer, the Apple II.

Jobs returned to Apple in 1997 when it purchased NeXT, a technology company he had founded in the interim. That same year, he was named CEO of Apple after the company posted huge losses.

Jobs reorganized the company, oversaw the launch of new devices and services, and gradually turned Apple into a trend-setting, money-making powerhouse. Today it is a major player in hardware, software and entertainment, with products ranging from desktops and laptops, to tablets, media players and smartphones, to online sales of music, movies and apps.

Apple overtook arch-rival Microsoft in 2010 to become the second most valuable U.S. company. On Aug. 9 of this year it was ranked No. 1, briefly displacing Exxon Mobil. Today Apple has a stunning market capitalization of $347 billion.

NeXT

Jobs’ technology and marketing skills worked magic at Apple, but his entrepreneurial record has a notable blemish - although it ended up fueling some of his biggest successes.

When he left Apple in 1985, Jobs poured his efforts into a new venture that he started the same year called NeXT Inc. His goal was to develop advanced computers for higher education and research.

The company won accolades in the technology community for innovative hardware and software designs and the graphics capabilities of its machines, but it didn’t sell many computers. The NeXT Cube, for example, was a commercial failure despite its advanced design, cutting-edge software and impressive computing power.

In an interview with the Smithsonian in 1995, Jobs said: "We basically wanted to keep doing what we were doing at Apple, to keep innovating. But we made a mistake, which was to try to follow the same formula we did at Apple, to make the whole widget. But the market was changing. The industry was changing. The scale was changing."

NeXT shipped fewer than 10,000 machines a year on average over the time it was in the hardware business, never becoming more than a niche player in the computer market. The company stopped making workstations and desktops in 1993 to focus on its NeXTStep operating system and advanced object-oriented software. NeXT never came close to becoming a household name.

Ironically, Apple ended up buying NeXT in 1997. Jobs returned to the company he’d helped to create, and engineered its incredible turnaround.

But it wasn’t just Jobs’ steady hand at the helm that put Apple back on a course to profitability. The hardware and software developments pioneered at NeXT were absorbed into Apple’s products, which helped them stand out from the competition. NeXTStep, for example, became part of the foundation for Apple’s move to the Unix-based Mac OS X. And NeXT’s graphics technology helped Apple build its reputation in the design and higher education markets – the goals Jobs had originally set for NeXT.

Lisa

Among the long string of hardware success stories, Apple has also had some less-than-successful launches. Development of the Lisa computer, for example, began in 1979 after Jobs got the idea that graphical interfaces (GUIs) would be the next big thing in computing, following a visit to Xerox Palo Alto Research Center (PARC).

The computer was supposedly named for Jobs' eldest daughter, Lisa Nicole, although Apple says it officially stands for Local Integrated Software Architecture. When it debuted in 1983, Jobs told the New York Times, "The industry's not had a real technical innovation in five years."

The first Lisa model had one megabyte of internal memory, a five-megabyte hard drive and came with six programs. A seventh program, for LISA to "communicate with other computers," was optional.

Lisa was said to be the best computer on the market for user friendliness. Here's how the Times described the experience in 1983: "Instead of typing instructions, one points to pictures on the screen by sliding a handheld device called a mouse along the top of the desk next to the computer. As the mouse moves, the cursor - the arrow that points to particular places on the screen - moves accordingly."

Lisa’s price tag was a whopping $10,000, which was one of the reasons it failed. By 1986, Apple was letting Lisa owners trade in their computer for a Macintosh Plus.

But Jobs again helped turn a miss into a hit. The Lisa was in a division headed by Jobs, Apple 32, whose other product was the Macintosh. While the LISA wasn’t a big seller, many of its innovations were built into the Macintosh, a faster machine with a much lower price tag that launched in 1984 and started the Mac – and the mouse-and-GUI – revolution.

Newton

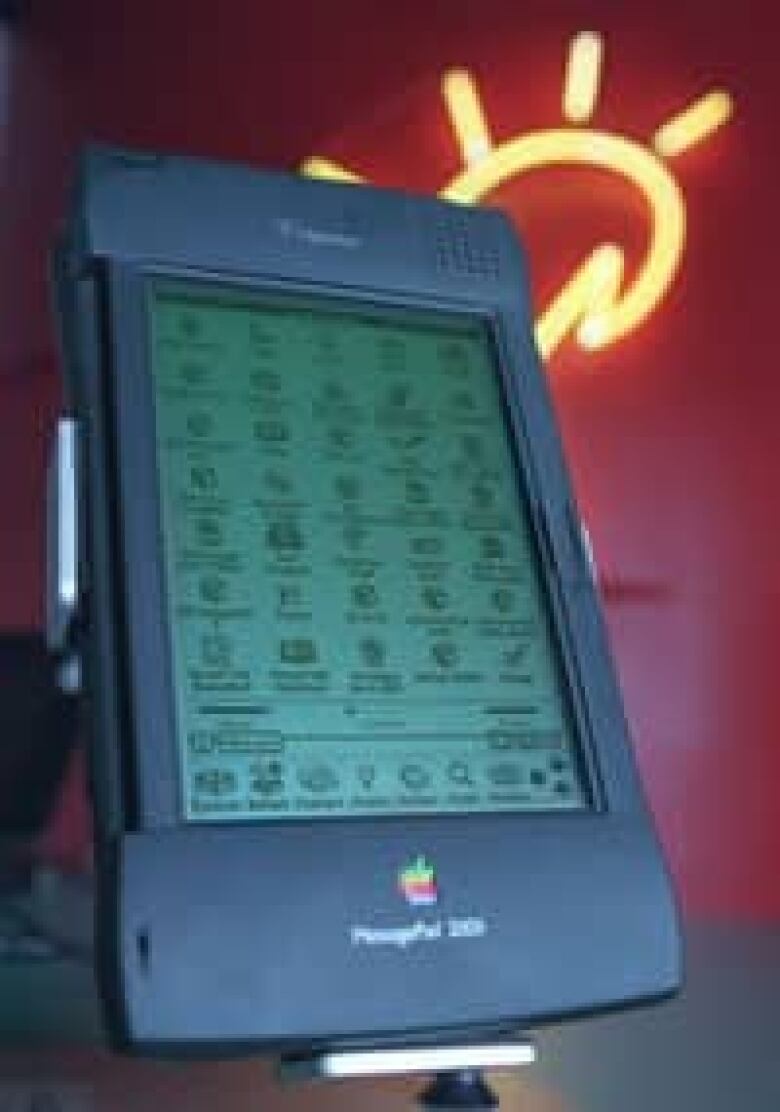

Lisa wasn’t the only flop for Apple. Before the smash-hit iPhone and the iPad, there was the Newton MessagePad personal digital assistant.

Development of the device, Apple’s first foray into PDAs, was done after Jobs was ousted from the company and during John Sculley’s time as Apple’s chief executive. Sculley, who is credited with introducing the term "personal digital assistant" in 1992, was the device’s major champion throughout its development. Just before it was due for release, he too was forced out of the company.

The Newton was plagued with problems — memory was one — and even mocked in the Doonesbury cartoon. It was a clunky and awkward to hold, and reportedly a money-loser for the company.

After Jobs returned to Apple in 1997, he killed several projects, including Newton. But in many ways the handheld device was simply ahead of its time. Jobs recognized this, and when mobile computing power caught up, rather than being scared off by Apple’s poor experience with handheld gear, he capitalized on it by launching products like the iPod and iPhone, which went on to devour the PDA market and become some of the best-selling consumer devices of all time.

In 2009, Apple rehired one of the original Newton developers, and revisited the idea of a next-generation PDA-like device with a touch screen. The result, the iPad, quickly created a massive market for tablets and dominated it in a way Sculley likely only dreamed of.

iTunes

It wasn’t just hardware that posed challenges for Jobs. iTunes was unveiled at the 2001 Macworld Exhibition, at a time stock analysts were increasingly negative about Apple, and it was a near-miss that turned into yet another monster hit.

"The PC or Mac can become the digital hub of our new digital lifestyle," he stated boldly at Macworld. After the exhibition, many analysts did not "believe he has shown enough startling innovations to turn around the company immediately," the New York Times reported at the time. iTunes also received lots of flack for its digital-rights management (DRM) locks on songs, and critics said it wouldn’t survive. Eleven months later, the iPod hit the stores, and the marriage with iTunes rewrote the rules for the music industry. Today, iTunes is the dominant software for both Macs and PCs for playing and organizing music, video and podcasts, and the billions in sales are a huge contributor to Apple's bottom line.

Pixar

Another Jobs venture that has had a huge impact on pop culture began rather inauspiciously. Pixar was founded in 1979 as a manufacturer of high-end computer hardware. Jobs purchased the company from Lucasfilm in 1986, shortly after he left Apple.

In 1995, Pixar released Toy Story, which went on to gross more than $360 million worldwide at the box office and is now seen as a game-changer in animated moviemaking. Pixar followed with A Bug’s Life (1998) and Toy Story 2 (1999), and has now released 11 films in total, including Oscar winners like The Incredibles, Ratatouille, Wall-E and Up.

In addition to their visual dazzle, Pixar’s films raised the bar on storytelling. Under the auspices of director John Lasseter and with Jobs’ backing, the screenplays were laced with pop culture references and emotional resonances rarely seen in animated films, to the point where films like Toy Story and Up are equally enjoyed by children and adults.

Pixar has also become a merchandising behemoth — offshoot products for the first Cars movie (2006) alone brought in $5 billion in sales.