Deleting your Instagram account won't solve the internet's hate problem

There are other ways to deal with online harassment than abandoning social media

Leslie Jones, Alec Baldwin, Keira Knightly, Stephen Fry, Lena Dunham, Zelda Williams, Miley Cyrus and Justin Bieber.

The list of celebrities who've been driven away from digital public spaces — where millions of us go each day to share bits of our lives with the world and our friends — grows exponentially longer each year, it seems.

This week alone saw U.S. Olympic gymnast Gabby Douglas, two supermodels, the mother of a murdered two-year-old boy and director Kevin Smith speak out against internet harassment, the latter on behalf of his 17-year-old daughter, who receives comments from strangers like "You're ugly as s--t... I sincerely hope you end up like Lindsay Lohan and dead."

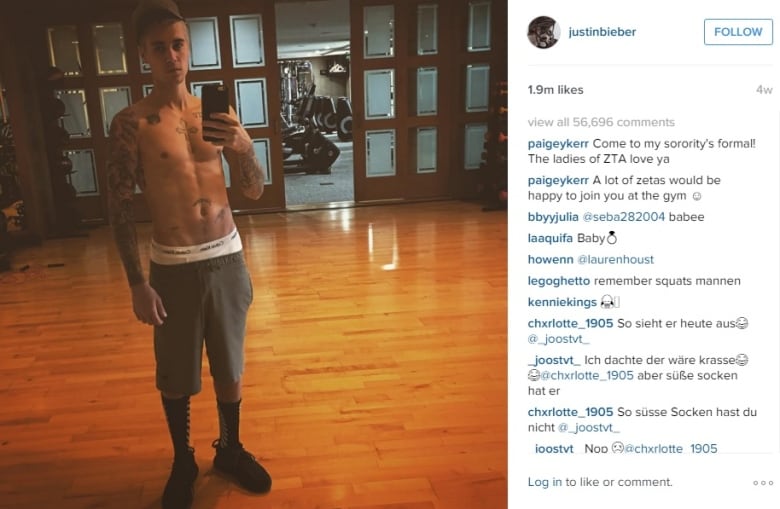

It was Bieber, though, who made the week's biggest statement when he shuttered his own Instagram profile under an onslaught of hateful comments from fans of ex-girlfriend Selena Gomez.

A bold move for the Canadian pop star, to be sure. For starters, he had one of the most valuable Instagram profiles in existence with over 77.8 million highly-engaged fans.

More relatable to most people, though, is that the 22-year-old performer really did seem to enjoy the platform. He was a prolific poster for years before his account went dark, and was known for sharing intimate photos and videos of himself with fans.

Even facing just a fraction of the hate hurled at some celebrities every day can be damaging to anyone, especially when it feels overwhelmingly unjustified.

Twitter, in particular, has long struggled with serious harassment issues, despite multiple initiatives designed to address the problem.

On Thursday, the company announced that it would soon begin rolling out new features that may help some users combat abuse, including a "quality filter." It remains to be seen if this will actually prevent abusive comments, or merely "address harassment by limiting what users will see in their feeds when they're logged on," as BuzzFeed suggests.

Instagram is also now testing a feature that allows users to filter comments. Ironically, though, it's currently only available to its most-followed users (like Bieber).

But what about regular people who encounter sustained hate and harassment online? People who aren't celebrities, but receive unwanted negative attention simply for sharing an opinion that gets amplified beyond their control?

Dai, who asked to be identified only by her first name because of recent and unsettling online encounters, shared her opinion Monday on Twitter about a controversial photo of TV host Ellen DeGeneres riding Olympic running champion Usain Bolt's back.

She was one of many people who were critical of the image tweeted by DeGeneres, which was lambasted by some as racist.

I am highly aware of the racism that exists in our country. It is the furthest thing from who I am.

—@TheEllenShowWhat she hadn't expected when publishing a tweet to her approximately 1,850 followers was that CNN would embed it in a news story, exposing her to the website's vast readership.

"It went crazy," Dai told CBC News of her notifications, explaining that strangers were saying "everything from that I don't deserve to exist, to that I should hang myself... that I should commit suicide."

Screenshots shared with CBC News by the Toronto-based advertising industry professional were similarly abusive, showing replies that called her names, attacked her gender, and overtly told her that she should take her own life.

Would you say that to my face? If you disagreed with my opinion on a celebrity's tweet in real life, would you tell me to jump off a bridge?- Dai, Toronto woman mass-flamed for comment on Ellen DeGeneres tweet

Dai protected her account almost immediately after becoming aware of the problem, but has spent days blocking and muting the hundreds of people who attacked her initially, and who continue to use her handle still despite the fact that they can't see what she's tweeting.

That said, she didn't skip a beat when asked whether she considered a full-on account deletion.

"Absolutely not," she said. "That wouldn't be fair."

"Just because my opinion differs from yours doesn't mean that I don't deserve to share it, or that I don't deserve to exist," she continued. "It's like, would you say that to my face? If you disagreed with my opinion on a celebrity's tweet in real life would you tell me to jump off a bridge?"

Probably not, says Thierry Plante of MediaSmarts, a Canadian not-for-profit organization for digital and media literacy.

"The internet and other electronic communication technologies have a lot of what we call 'empathy traps," he told CBC News. "A lot of the harassment comes from essentially forgetting, at least on an emotional level, that you're dealing with an actual, real person on the other end."

AM I TOO SKINNY OR TOO FAT TROLLS PLZ BE CONSISTENT OR I WONT KNO HOW TO CHANGE MYSELF 4U <a href="https://t.co/SE2BthWfEx">pic.twitter.com/SE2BthWfEx</a>

—@KatTimpfPlante says that, while sexist, racist, regular harassment like the kind seen in some Twitter communities can have effects on a person's mental health, shutting down your social media profile because of vicious strangers isn't the only option — especially if you otherwise enjoy a specific social network or use it in the context of your career.

Don't feed the trolls, but do record them

As much fun as it may look to clap-back at haters like model Gigi Hadid on Instagram, conventional wisdom holds that you should never "feed the trolls" — as in, you shouldn't reply to excessively harsh messages or engage with people who send them.

Plante agrees, with one caveat: "Indeed, you don't feed the troll. But you do record it."

He recommends taking screenshots to "start building a record of what's happening." This material could prove crucial if ever you need to report someone to the authorities. Tweets can be deleted, but images of them can be stored on your hard drive for future reference

There are different tools designed for flagging and filtering abuse on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. They may not always solve the problem, but can be helpful in some situations. Likewise for connecting with positive people and what Plante calls "helpers and change makers" to help you police the harassment.

- We 'haven't quite got the formula down' to fight bad behaviour on social media

- Social media giants pledge to review hate complaints within 1 day

- 'We suck,' Twitter CEO admits about stopping internet abuse

It's also a good idea to read up on what's legal and what's not legal where you live in real life.

"Find the specific definitions of libel, defamation or definition of threats online that are in the criminal code," Plante says, "and you can report those with the evidence you have to police."

If you want to ditch the glossy world of Instagram for good, hey — you'd be far from the first. Just know that you also have the option to temporarily deactivate your account (as Bieber may very well be doing) and come back to it later.

Sometimes, even just putting the phone down for a while and focusing on something other than the harassment can be a positive step. "You have to learn to step away, reduce your exposure," says Plante.

"When you sleep with your cellphone, you remove one of the safest spaces you have. Traditional bullying used to end when you got to your house. Now it has the potential to come with you to bed."