Drivers licences with chips spark heated debate

The licences have embedded radio-frequency identification (RFID) chips that can broadcast information wirelessly to a nearby reader. While that can make identifying people much faster and easier, it has also raised fears that the technology could be abused or hacked by ID thieves.

Despite the controversy, federal and provincial governments in Canada are committed to adopting the same model to harmonize Canadian EDLs, which the U.S. will accept in lieu of passports.

Under the U.S. Western Hemisphere Travel Initiative (WHTI), passports or EDLs will be required for all travellers entering the U.S. starting June 2009, so provinces are introducing EDLs on a voluntary basis to speed up border crossings. In January, for example, British Columbia became the first province to run a trial EDL program. Manitoba introduced them in May. Quebec and other provinces are working on similar pilot projects, says Mélisa Leclerc, director of communications at the Ministry of Public Safety. The Ontario government introduced legislation in June that would clear the way for the new licenses.

"The federal government is very supportive of EDLs and other initiatives to ease the legitimate flow of trade and travellers across the border, and is encouraging provinces to come up with plans for its approval," Leclerc says.

What is RFID?

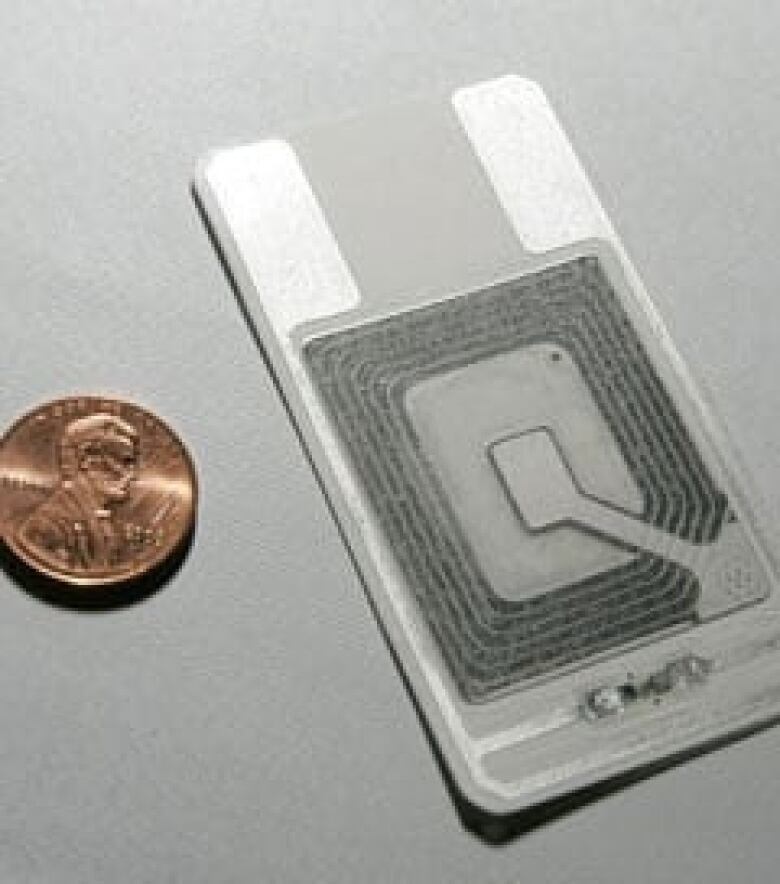

Radio Frequency Identification, or RFID, is a generic term for technology that uses radio waves to identify people or objects. Information ranging from a simple serial number to more complex data is carried on a microchip with an antenna that can be as small as a grain of sand.

A RFID system consists of a tag - made up of a microchip with an antenna - a reader and a database.

Some RFID tags have their own on-board power source, but the more widely used "passive" tags draw their power wirelessly from the reader. The reader sends out electromagnetic waves, and when these waves hit a passive RFID tag antenna the microchip draws power from them and uses it to activate its circuits. The chip then sends back its own set of waves containing information, which the reader converts into digital data.

Passive tags have a limited range, with a typical range of just a metre and a maximum range of around 12 metres. Larger "active" tags with their own battery power can be read from distances of 100 metres or more.

The goal in most provinces is to offer a document that's cheaper and easier to carry than a passport, says Marilyn McLaren, CEO of Crown corporation Manitoba Public Insurance. "We believe EDLs should cost less than half a passport, which is about $100," she says. "People get stressed about carrying a passport, and many find something that's like a credit card more attractive."

Not everyone is enthusiastic, however, about the idea of EDLs based on wireless RFID technology. "Developing a high-tech RFID system plays better politically in the U.S., but it's security theatre to make borders appear more secure than they really are," says Andrew Clement, professor of information studies at the University of Toronto.

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and members of the RFID industry have expressed serious concerns about the security protocols used in the EDL technology model developed by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS), for example.

The RFID tags used in EDLs work by emitting a signal that contains an individual's serial number. The signal can be read by guards equipped with RFID readers at border crossings. But privacy advocates point out that the EPC Gen 2 RFID protocol developed by the DHS for electronic drivers licences doesn't support encryption and can be read from a distance of up to 6 metres.

Demonstrations of the technology's failings have showed that RFID signals emanating from a crowd of people carrying RFID-enabled cards can be easily and covertly picked up by someone nearby carrying a RFID reader in a suitcase, says Clement. "It's uncalled for to use RFID tags that can be read at such a long range - it's over-reach for the task they're claiming it's for."

Secure database

Representatives of Beaverton, Oregon-based Digimarc Corp., the security firm that designed the EDL system for the DHS, maintain that the RFID tags are secure due to the way the EDL system operates.

"It's not an ID tag," explains Andy Mallinger, senior director of product marketing, referring to the number broadcast by EDLs. "It's a meaningless number that's not associated with an individual's passport or anything else. Yes, it can be read in some circumstances, but I don't think reading it represents a security risk."

Mallinger says the number can only be associated with an individual's identity and personal information when border guards match the RFID serial number to the corresponding record in a highly secure EDL database.

The tags are designed to be read from a distance so guards can pull up records in advance when a vehicle approaches a check-point. Travellers still have to stop and undergo the usual questioning and processing done at the border, but the guard would instantly have information available about the vehicle's occupants instead of having to type or scan passport information manually into a computer.

"EDLs aren't for unfettered crossing," Mallinger says. "The reason it's read before people get to the booth is so the guards don't have to wait the few seconds for the record to come up in the database. It cuts time so traffic can be moved through the border quickly."

But correlating people's identities with the EDL's serial number is fairly easy even without hacking into the corresponding database, says Bruce Schneier, a security expert and chief technology officer of BT Counterpane, a managed security provider based in Santa Clara, Calif.

"The idea that a random number can never be linked to your name seems farcical," he says. "Your identity is something you leave lying around all the time when you buy something with a credit card, show your ID when you enter a bar, and so on."

With a minor bit of legwork, criminals could easily link an EDL's serial number to a licence plate as a person enters their car, and correlate it to the person's identity from there. And insiders often abuse personal information: store clerks frequently steal people's credit cards by correlating names to numbers, for example, and there have been several cases of government workers stealing peoples' government-issued ID numbers.

For its part, the Manitoba government weighed the pros and cons in its decision to introduce EDLs, says Manitoba Public Insurance's McLaren. "It's the American government's prerogative to decide what meets their standards for an acceptable alternative to passports, and they require RFID chips in these documents."

However, Manitoba has taken steps to mitigate privacy fears, says McLaren. "To protect against identity theft, we're offering a protective sleeve that prevents the EDL from transmitting its signal until it's taken out."

Political signals

Security is just one of the issues surrounding RFID-based EDLs. Canadian privacy advocates are also questioning the underlying rationale for the post-9/11 EDL initiative.

Where is RFID used?

In more places than you think.

RFID tags were originally used to track Allied aircraft in the Second World War so they wouldn't be shot down by friendly fire. They were later used to track railway cars and cattle.

As the chips have gotten smaller their uses have multiplied. Warehouses and big retail chains like Wal-Mart have used RFID as an upgrade over barcode technology to track inventory, for example.

Tags can now keep track of everything from store credit cards to merchandise like clothing, diapers, and automobiles. Some countries have put RFID technology in passports and library books. They can even be placed in living things, from pets to people.

"Is RFID technology really necessary for this purpose?" asks Clement. "That's an important question - if the U.S. just wants citizen information collected at its borders, there are less problematic ways to do it."

Schneier agrees more secure approaches could easily be used instead. "The reason RFID is bad is because the number is constantly broadcast. The way to solve this problem is to make an EDL like a phone card that you stick in a slot."

There appear to be wider issues at play, says Clement. "This needs to be seen in the context of a general push for security across a range of realms. As the Privacy Commissioner of Canada has noted, EDLs seem to be a way of enrolling Canadians into the ID schemes being developed by the DHS."

Clement explains that the Real ID Act enacted in 2005 calls for the harmonization of drivers' licences across states in the U.S., as there's widespread recognition they aren't secure. Americans can get licences in multiple states, and there's no systematic way of verifying people's identities or checking inconsistencies across state lines.

But in the U.S., identity and citizenship are folded into drivers' licences. "There was big thrust after 9/11 to create a national ID, but there was huge opposition," Clement says. "The EDL scheme is seen as a way to sneak it through the back door by turning drivers' licences into de facto identity cards. Canadians will in fact be enrolled in the U.S. apparatus via EDLs. There are several steps to get there, but this seems to be the direction it's heading towards."

Although Canadians won't be in official government databases, their data will likely be stored when they cross the border, says Schneier. "The government could snoop on all manner of activities if Canadians buy things, use Google and Hotmail while they're in the U.S."

Are EDLs the right approach?

Provinces with significant traffic of people and goods across the U.S. border do face a genuine dilemma, says Clement. Many local economies depend on cross-border flows, and keeping that flow fast and smooth is important. But the irony is that the EDL model has no more underlying rigour than other forms of ID such as Canada's citizen card, and ultimately doesn't serve the anti-terrorism agenda, he says.

And even if more secure, next-generation RFID technology were used, many privacy advocates would not be satisfied because of the potential for the information to be used and the precedent it sets.

"There is too much room for abuse even in more secure RFID," says Stuart Trew, researcher at the Council of Canadians, which has 70,000 members and is Canada's largest citizens' advocacy group. EDLs are a step towards the slippery slope of creating a surveillance state, he adds.

"The concern is that RFID scanners will start popping up in trains and bus stations everywhere, not just border checkpoints," says Trew.

He says documents obtained by American privacy advocates under freedom of information requests show that discussions held under the auspices of the Security and Prosperity Partnership, a 2005 agreement between the U.S., Canada and Mexico, have proposed widening surveillance of travellers. "They're considering real-time monitoring of travel throughout North America with RFID chips that can be perpetually read."

Clement speculates that the EDL initiative being pushed in the U.S. has more to do with illegal Mexican immigrants than anti-terrorism. Although proponents say the prime motivation is anti-terrorism, the EDL initiative doesn't address many of the key issues in border security.

"By offering EDLs, provinces are trying to ease questions about cross-border flows, particularly for nearby communities that are accustomed to travelling across freely. But the fact that Canada's citizen card is not acceptable suggests there's a wider agenda," he says.

"This high-tech solution is a bit of a mirage," Clement adds. "In my opinion, the main concern is the Mexican border, which is hot political issue. Presidential candidates are all saying they'll secure the borders. They want something that looks more robust, and just asking for a citizen card doesn't seem more secure."

However, there are signs that the Bush administration's anti-terrorism programmes and policies are in disarray, he adds. "Let's hope the U.S. administration under a new president comes to its senses."