Researchers discover 'Dracula's terrible tick' trapped in amber with dinosaur feather

Scientists say this is first evidence that ticks fed on feathered dinosaurs

Scientists examining 99-million-year-old amber hit pay dirt when they discovered both the first direct evidence of a tick feeding off a feathered dinosaur, and also an entirely new species of tick.

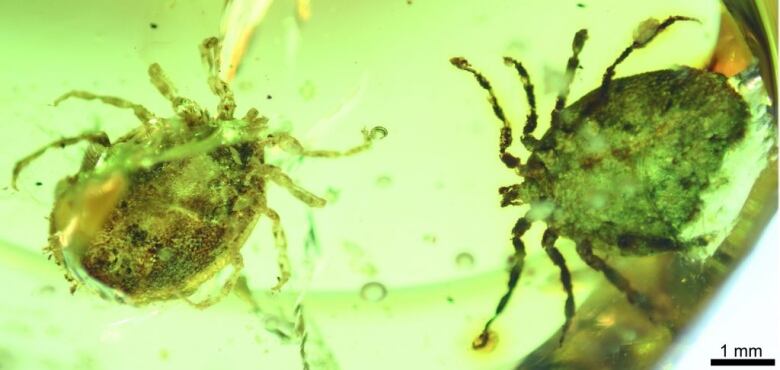

Two specimens of the newly discovered species, Deinocroton draculi — "Dracula's terrible tick" — were found trapped inside the Burmese amber.

While feathers and ticks previously have been found together in amber, there had never been direct evidence of ticks feeding off a dinosaur.

- Scientists find baby bird trapped in 99-million-year-old amber

- Feathered dinosaur tail found trapped in amber

"It was something that several authors had posited in the past," said Ricardo Perez-de-la Fuente, co-author of the paper published in the journal Nature Communications. "Ticks have already been found in Cretaceous amber, especially from Burma....but they were not associated with any organic remains."

Without evidence of ticks actually interacting with organic remains, such as feathers, paleontologists couldn't say for certain that ticks were feeding on dinosaurs. These ticks are found attached to the feather, proving they were feeding.

"Although we can't be sure what kind of dinosaur the tick was feeding on, the mid-Cretaceous age of the Burmese amber confirms that the feather certainly did not belong to a modern bird, as these appeared much later in theropod evolution according to current fossil and molecular evidence."

'Very rare'

In total, the researchers found five specimens of the new ticks and two others of another already known species that were preserved together.

"Having two...preserved in the same piece is a very rare circumstance," Perez-de-la Fuente said. "Which leads us to think that they were trapped together while visiting the host's nest."

And having so many specimens provides a glimpse into the past.

"Ticks are infamous blood-sucking, parasitic organisms, having a tremendous impact on the health of humans, livestock, pets and even wildlife, but until now clear evidence of their role in deep time has been lacking," said Enrique Penalver, from the Spanish Geological Survey (IGME), lead author of the work.

"The good thing about having multiple specimens is that each of the specimens is actually providing different information," he said. "For example, the two ticks preserved together are males.... But we also have a female that is preserved in a separate piece of amber, and that particular female is not engorged in blood but the other [female] is," he said.

"So we can compare them; we can actually see what the differences are and what that blood engorgement entails."

Hard vs. soft ticks

Ticks are classified into three groups, Perez-de-la Fuente said: soft-bodied, hard-bodied and one tick that is only found in Africa, called Nuttalliellidae. This unique tick is believed to be the closest living relative to ancestral ticks and displays different behaviours than either of those. It's a more like a soft tick that behaves like a hard tick.

Soft ticks have multiple feeding cycles, where they detach from the host, lay their eggs and then return to feed, increasing their body volume 10-fold.

Hard ticks, on the other hand, only feed once in their lifetimes, and because they need to store their food, increase their body volume up to 100 times.

"It can be very disgusting, actually, to look at the pictures," Perez-de-la Fuente said of the massively engorged ticks.

Since the engorged ticks found in the amber have swelled almost eight times, this leads the researchers to believe the species had multiple feeding cycles, similar to soft ticks.

Missing link of ticks

But it's not quite that simple. The ticks found in the amber have a hard shell, not a soft one.

"It's interesting to see that our ticks resemble that supposed missing link between the past ticks and the modern ticks, [similar to] the Nuttalliellidae," Perez-de-la Fuente said.

And while at the moment, it's impossible to extract any DNA from the engorged samples, as was done in the book and movie Jurassic Park, Perez-de-la Fuente isn't ruling it out entirely.

"With modern techniques, who knows if in the future this is going to change, because science advances at a very, very high rate," he said.

Unfortunately, though, even if science does advance to eliminate any potential contamination from humans, the DNA won't come from these ticks. Though they are engorged with blood, they were preserved together with iron, which contaminated the sample at its source.