Climate change: CO2 emissions fall in 18 countries with strong policies, study finds

'You develop the policies, you fund them, and then you get emission decreases"

In a new study published in the journal Nature Climate Change, researchers suggest that countries that are turning to renewable energy sources and moving away from fossil fuels are making progress in reducing CO2 emissions.

The study looked at emissions from between 2005 and 2015. Globally, CO2 was on the rise — about 2.2 per cent annually — but in 18 countries, their emissions saw a decline. These 18 account for 28 per cent of global emissions.

"We went in these 18 countries and looked at what policies they had in place … and we found that, in the countries where there's more policy in place, the decreases in emissions were larger," said Corinne Le Quéré, a Canadian professor of climate change science at the University of East Anglia in the U.K. "That suggests that the policies do work."

But another contributing factor, they found, was that these countries were also using less energy overall. They might have more efficient heating systems, or more electric cars on the roads, for example.

While it may seem like common sense — better policies beget positive outcomes — there are other factors, such as economic growth (or decline) that influences emissions and energy output. For example, the researchers did find that the financial crisis of 2008–2009 showed up in the data, with a decrease in emissions.

What the researchers found most encouraging about their study is that, for the two countries that were the control group, if you removed their economic growth, policies encouraging energy efficiency were linked to cuts in emissions.

"Really, this study shows it's not a mystery. We have the technology: you put the effort in place, you develop the policies, you fund them, and then you get emission decreases," Le Quéré said.

Unfortunately, Canada didn't make the list. Emissions in Canada decreased by about half a per cent, Le Quéré said, compared to some countries that saw a three or four per cent decrease.

"One of the messages that comes out of our analysis is that policy matters, and the efforts of policies," she said. "You need to have a lot of big policies in place and policies at the national level; policies that are well-funded, that are regulated."

However, she did note that emissions are decreasing in Canada, albeit slowly.

And though China, the world's biggest CO2 emitter, didn't make the list of 18 countries, their emissions have flatlined, she said.

Hope

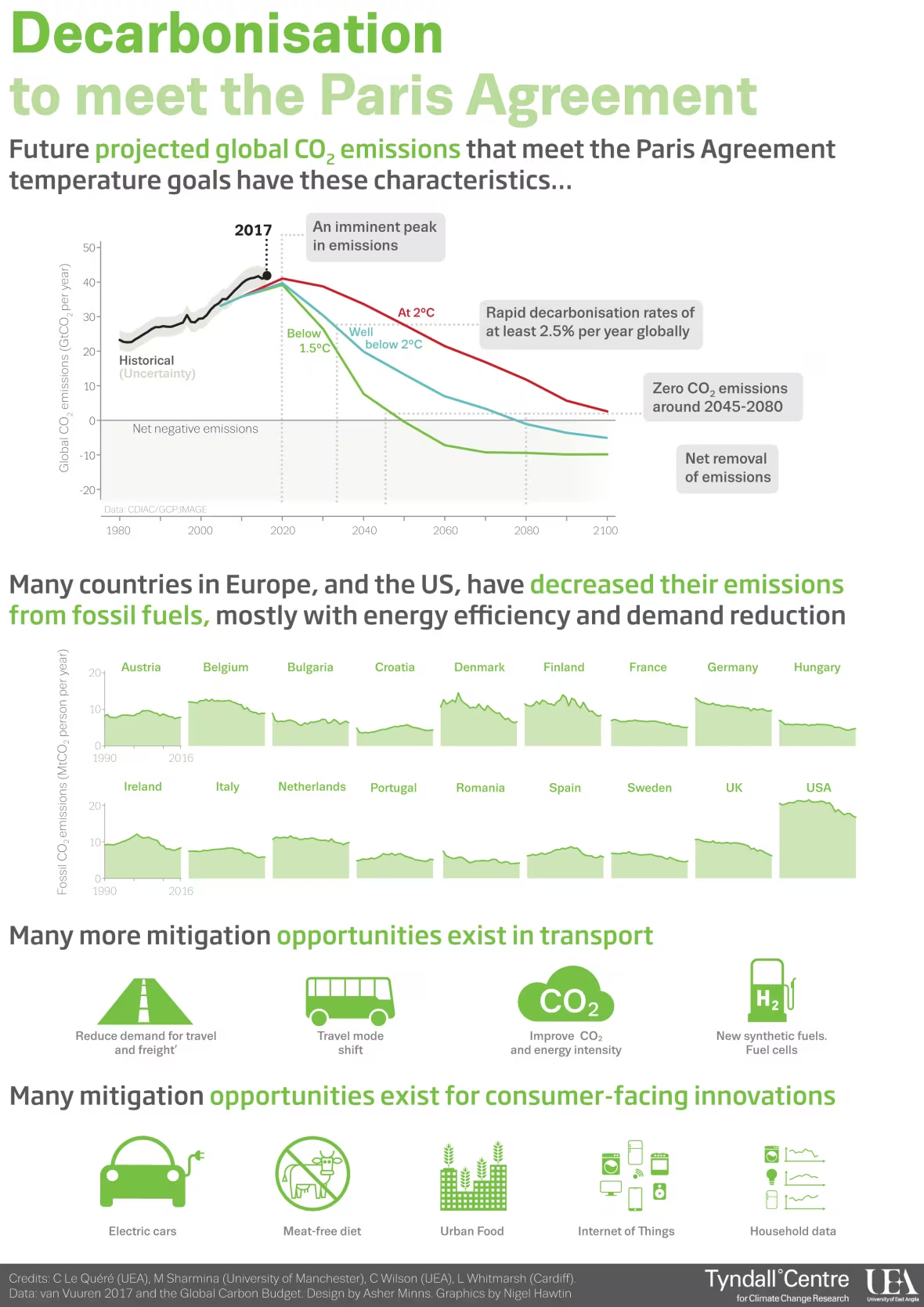

The researcher said that, while many countries are making an effort to reduce emissions, more needs to be done if we're to keep below 2 C of warming, a target set out by the Paris Agreement.

Climatologist Michael Mann, a professor at Penn State University in Pennsylvania and director of the university's Earth System Science Center has hope.

"There is still an available path to stabilizing greenhouse warming below 2 C, a common threshold for defining dangerous human interference with the global climate," he said. "But it requires a rapid decrease in carbon emissions (about 10 per cent a year over the next decade) at a time when emissions have shown a small uptick."

He notes that these 18 countries are already ahead of the game when it comes to a renewable, energy-driven economy.

At a time when scientists are science communicators are trying to find more effective ways of communicating the impending threat of climate change, this study, the authors say, illustrate some positive news.

"New scientific research on climate change tends to ring the alarm bells ever more loudly," said co-author Charlie Wilson, also from East Anglia. "Our findings add a thin sliver of hope."

Le Quéré said that countries need to invest more in renewables in order to make the cost come down, much in the same way that was done with solar energy.

"What we're learning from the experience so far is that learning by doing pays off a lot," she said.

Mann, who is well-known for the "hockey stick graph" he produced in the 1998, illustrating a rapid rise in global temperatures, is also telling people that there is hope if we change to renewable energy.

"There is a clear path toward averting catastrophic climate change," he said. "We just have to follow it."