'Why did it take so long?' Pope's apology allows one residential school survivor to face hidden past

Survivor says wait for apology was painful, but words helped him share personal truth

WARNING: This story contains distressing details.

For 58 years, Norman Yakeula kept part of his residential school experience hidden, sharing only pieces at a time to protect himself from feeling the pain of the open wounds that remained.

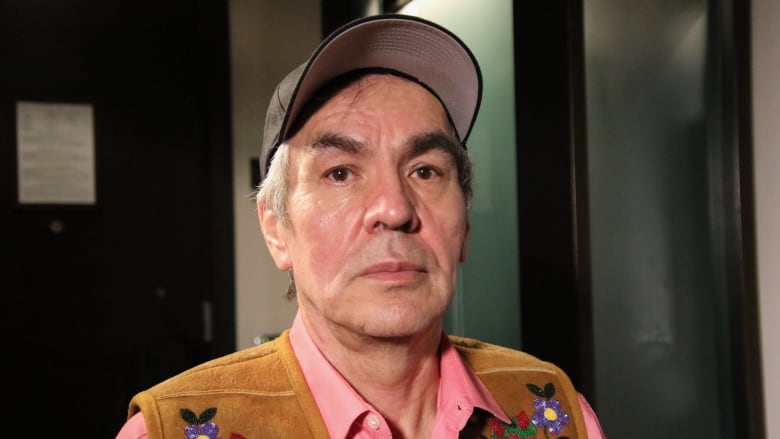

But after travelling to Rome to hear from Pope Francis, Yakeula, 63, asked to sit down with CBC News to share a long-hidden part of his story.

"I got this at five years old," said Yakeula, as he lifted up the pink dress shirt he wore to Friday's final audience with the Pope, First Nations, Inuit and Métis delegates at the Vatican.

Yakeula reveals a long scar with 17 faded imprints of stitches across the right side of his abdomen.

"This is what I live with every day," said Yakeula, who is from Tulita, N.W.T, but now lives in Yellowknife.

"I'm reminded of what happened to me. That's how deep the hurt goes."

Yakeula, a former Dene national chief and Assembly of First Nations regional chief for the Northwest Territories, wrote his last name as "Yakeleya" for most of his life — the spelling given to him while attending Grollier Hall, the Roman Catholic-run residential school in Inuvik, N.W.T.

He recently changed it to its original form of Yakeula, which means "singing in the heavens" in the Dene language.

"That's the name that I have to recognize and respect," he said.

For decades, Yakeula said he was ashamed of his scar. As a child, he always swam with a shirt on to hide it. Now, Yakeula said he's ready to publicly reveal what happened to him to show the truth about those who ran the Catholic residential school.

"While I was here in Rome, I always protected that," Yakeula said.

"Today, I want to share because I'm getting closer to not feeling the same about it."

Residential school didn't seek mom's consent for operation

During his first year at Grollier Hall, Yakeula said he was sent to the hospital by school supervisors and doctors decided to operate on him.

At the time, he said he was told the doctor needed to remove a birthmark.

To this day, he wonders what really happened to him. What is clear — the operation left a lasting mark on him that caused him both physical and emotional pain for decades.

"After the operation … I couldn't move," Yakeula said. "I was sore, I was crying for my mom. It was sore. I don't know why they cut me."

Yakeula can still vividly recall having to relearn how to walk at the age of five with a chair.

His mother Laura Lennie only found out about the surgery when Yakeula returned from residential school for the summer in June.

"Mom was giving us a bath in the bathtub and took my shirt off, and she looked at me and said, 'What happened to you?' I said, 'Mom they cut me,'" he said.

"My mom started crying. She said, 'When?' I said, 'When I was in Grollier Hall.'"

Bishop says Pope wanted to establish personal relationship with survivors

Yakeula felt flashbacks when he heard Pope Francis apologize last Friday for the conduct of some Roman Catholic Church members at residential schools.

"I was thinking, since I was five years old until today, why did it take so long for four words: I am very sorry? Why did you put me and many others through this painful process?" Yakeula said.

"He could have said it when my mom was still alive, my cousins still alive, my sisters … The Bible says the truth will set you free. That's the truth. That's all we wanted."

The Pope's initial residential school apology comes too late for Yakeula's mom and many other survivors — six years after the Truth and Reconciliation Commission called for a papal apology.

"Yes, maybe it has taken this time," said Calgary Bishop William McGrattan.

"But in time we continue to walk this path of reconciliation, and hopefully we can build upon what he himself has expressed, what the Canadian bishops have expressed, and hopefully we can continue to work toward and make concrete signs of that reconciliation and that apology."

McGrattan said Pope Francis needed to establish a personal connection with survivors before delivering a personal apology.

"It's very important for the Holy Father to listen and then to express with a genuineness that this experience truly moved him," said the Calgary bishop during Friday's news conference after the Pope's speech.

"As a result of that, he expressed that apology, I believe, from the sincerity of his heart after listening to many of the stories this week."

Breaking the shell of residential school cocoon

Yakeula said he got angry after the apology, took some time to rest, and woke up with a sense of relief.

But he said the Pope still needs to offer a full apology on Canadian soil. Pope Francis told the First Nations, Inuit and Métis delegates that he hoped to visit Canada this summer.

When he comes, Yakeula said he wants the Pope to visit his mom's grave.

"He's got to come to our land," Yakeula said. "This is not done yet."

Yakeula said meeting with the Pope allowed him to face his own experience in a way he couldn't before.

"We are like the cocoon where we are breaking the shell of the residential school and that transformation to become who we were meant to be before the residential school, and that's a painful process," Yakeula said.

"We had the past in front of us and that was our future: hurt, shame, pain. Today, we want to put that pain in the past where it belongs so our people, and especially our young children, do not have to carry it for us."

Church taking the shame back

Yakeula said the Roman Catholic Church put shame upon shame on residential school survivors.

With the Pope asking for God's forgiveness, Yakeula said the church has taken that shame back.

"That's not our shame," Yakeula said. "Today is good. They accepted that responsibility."

Yakeula, who calls himself a residential school freedom fighter, said the apology is a first step toward healing.

Now, he said action is needed and he would like to reignite a national survivors group, work with the church and youth moving forward.

"We've come this far. Now it's our turn, as survivors, to just do it," he said.

"Make things happen for our young people … Lead them to the path of reconciliation."

Support is available for anyone affected by their experience at residential schools or by the latest reports. A national Indian Residential School Crisis Line has been set up to provide support for former students and those affected. People can access emotional and crisis referral services by calling the 24-hour national crisis line: 1-866-925-4419.