Opioid stats coming into focus, but impact on Indigenous communities largely unknown

Lack of 'fair and even access' to treatment on First Nations a problem, says new Indigenous services minister

The parking lot at the gas station on this New Brunswick reserve is empty except for a lone man sitting on a bench, sipping a can of iced tea and finishing his cigarette.

We're calling him Stephen, which is not his real name. And we're not saying the name of the reserve where we've agreed to meet on an unexpectedly hot September day.

That's because what he's telling us about is the illicit opioids he sells to residents here.

"These people are going to keep coming back, keep coming back and no matter what," he said. "It's also impossible to get off [opioids] without medical help. Like, you can't just do it cold-turkey — the withdrawals are so intense."

Stephen says the deadly opioid fentanyl has made its way to New Brunswick, primarily Moncton.

He claims he hasn't cut fentanyl into the drugs he sells, even if it would increase profits.

He says the drug is at its most dangerous when it first arrives in a community.

"All depends on who is cutting it and how good they are at cutting it," he says. "And apparently fentanyl is hard to cut — it comes in like a gel from a patch. The danger and the threat of a bad batch coming out would be higher."

Few opioid stats on Indigenous communities

The extent of the opioid crisis sweeping Canada has been hard for researchers to quantify.

It's been especially hard to get any data on Indigenous communities, which experts say are among the hardest-hit.

The delivery of health care for status Indians is largely the responsibility of the federal government, but neither Health Canada nor the Indigenous Affairs Department track opioid overdoses on reserves.

A new report from the Canadian Institute for Health Information released this week was able to break down opioid-poisoning hospitalizations at a municipal level, but it didn't have data for Indigenous communities.

But an August report from British Columbia's First Nations Health Authority and the provincial government showed First Nations people in B.C. are five times more likely to experience an overdose and three times more likely to die from one than non-Indigenous people.

- 'Such courage': How one First Nation is fighting opioid addiction

- Opioids land 16 Canadians in hospital each day, 53% jump over 10 years

Ontario regional Chief Isadore Day said that's likely the trend in other provinces and territories as well.

"The issue of opioids in our First Nation communities is a tragic emergency that has been there for quite some time," he said. "I would even call it a crisis that has been long-standing for the last, say, 15 years."

Emerging numbers 'highly disturbing'

Day, who is also national chair of the Assembly of First Nations chiefs' committee on health, said services are already subpar on reserves without mixing in contaminated illicit drugs.

Opioids are even a problem in the so-called dry communities, where alcohol is prohibited, because they're "more concealable" and "more accessible" as prescription drugs, Day said.

"Our communities are experiencing a major impact from the multigenerational issues of trauma and addictions," he said.

Former federal health minister Jane Philpott, who is adjusting to her new job as Indigenous Services Minister, has seen the B.C. numbers.

"The fact that some Canadians are much more vulnerable than others is highly disturbing, and it's something we are absolutely determined to work with our partners on," she said in an interview.

"First Nation Canadians are disproportionately affected," Philpott said, because there isn't "fair and even access" to addiction treatment.

Philpott said the government is making progress with the opioid epidemic every week, but the issue in Indigenous communities comes with other considerations.

"We need to address this both in terms of making sure people have access to the kind of treatment facilities that are necessary but also getting at those real root causes and addressing trauma, identifying it, getting people opportunities for healing in a way that's culturally sensitive."

Concerns about consultations

Despite the disturbing trends, Day said Indigenous people were left out of the federal government's joint statement addressing the crisis with provinces and other stakeholders last year.

"We didn't support Canada's opioids strategy about a year or so ago, because clearly we were not consulted," he said. "The AFN simply said, 'Listen, we can't support this at this time because you don't even know what our issues are.'"

Those issues include funding to adequately pay frontline workers on First Nations, who, Day said, are "having to deal with the treachery of the opioid addiction in our communities."

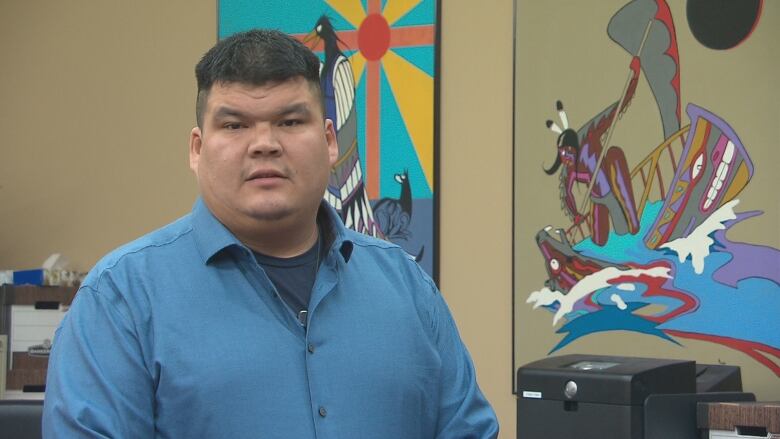

Elsipogtog First Nations Chief Arren Sock is trying to keep that treachery at bay.

At the band council office on the eastern New Brunswick reserve there's a sign taped in the window warning of the "high probability" fentanyl has made its way into the community and threatening to expel or ban traffickers.

A woman from Esgenoôpetitj First Nation, about 100 kilometres north of Elsipogtog, died from a suspected fentanyl overdose this past spring.

"We're working closely with the RCMP, our local detachment, and basically just trying to do everything we can to avoid this crisis," said Sock from the council chambers, which doubles as a courthouse on Wednesdays. "We've started to gather our own resources in terms of what we have: mental health, enforcement, involving the school principal, our health department, our pharmacist."

The dark fentanyl cloud is just the latest threat stressing his already thin resources.

"It's been an ongoing problem for at least 150 years. The federal government [is lacking] in terms of supporting First Nations," said Sock. "From one prime minister to the next, it's always the same rhetoric."

CBC Radio's The House will have a special show Saturday, Sept. 16, about the opioid crisis in Canada.

Tune in at 9:00 a.m., 9:30 a.m. in Newfoundland, or find the episode here.