Election polling station 'errors' raise troubling questions

For Borys Wrzesnewskyj, the 2011 election story is not about robo-calls. The former Liberal MP for Etobicoke Centre suspects he was robbed, but not by Pierre Poutine and his disposable cellphone.

Rather, he thinks he may have been doomed by a lax application of the rules governing who may vote and where. Citing 181 dubious votes, Wrzesnewskyj is suing for another chance to win the riding he lost, by just 26 votes, to Conservative Ted Opitz.

That there were mistakes is not in doubt. But, for Elections Canada, "clerical errors" should not mean that voters are disenfranchised or an election overturned. For the court, the question is whether such errors affected the result.

To date, the Etobicoke case has revealed a tangled tale of sloppy paperwork, some of which is ascribed to a natural instinct on the part of Elections Canada officials to facilitate voting, rather than to obstruct it with red tape.

But, still: a whole range of problems has turned up which seem to push the boundaries of what's normal.

Did some voters vote twice? It seems possible. Did some vote in the wrong riding? Again, it's possible. Were there some who do live in the riding but voted in the wrong polling station? That's possible, too. Did they also vote in the right one? Not impossible.

And what about voters whose proof of eligibility can't be found? If they forgot to bring their ID, did someone else vouch for them — and, if so, who? Where are the records? If there are no records, how do we know that nobody vouched for more than one person — which they're not allowed to do? And, even if they just vouched once, how do we know they're eligible?

To date, nobody's proved — or even alleged — anything but innocent mistakes. But, at some point, Wrzesnewskyj believes, mistakes may be too numerous for the election to be credible. And Part 20 of the Canada Elections Act allows challenges in cases of "irregularities, fraud, corrupt or illegal practices that affected the results."

"This isn't a Liberal or a Conservative issue. This is an issue that touches everyone," argued Wrzesnewskyj's lawyer, Gavin Tighe. "If people have no confidence in the process, it's pretty doubtful they’re going to participate."

David Di Paolo, a lawyer for the chief electoral officer, Marc Mayrand, responded that "administrative and clerical errors in elections will be common and, indeed, inevitable and it is essential that only those consequential to the result be used to overturn an election."

Are 'special ballots' really special?

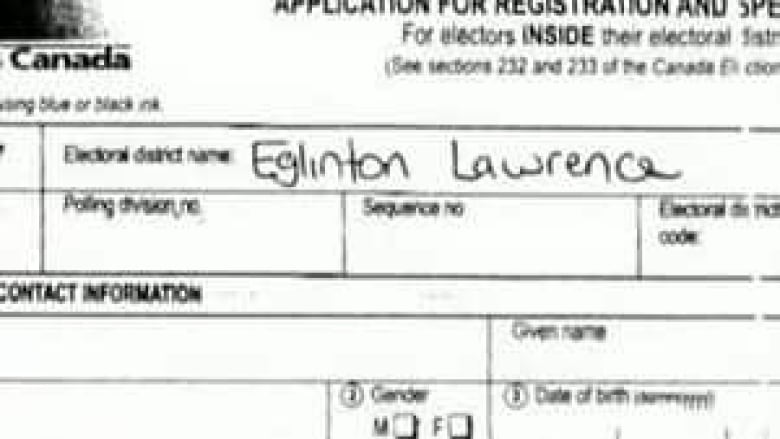

Then there's the thorny subject of "special ballots." Such ballots are available to people who can't get to the polls, either on election day or at the advance polls. They can apply for one if they prove they're on the voters' list or, if they're not on the list, they can prove they're eligible. In each case, they have to fill out a form correctly.

But what if they don't — and get to vote anyway?

In the nearby riding of Eglinton Lawrence, these issues contribute to a continuing unease about the 2011 election. This time, the Liberal who lost, Joe Volpe, has not taken the case to court — and it wasn't really close, in any case. Conservative Joe Oliver won handily, by more than 4,000 votes.

Even so, Eglinton Lawrence presents its own set of questions.

For one thing, Eglinton Lawrence was plagued with bogus phone calls. During the campaign, the Volpe team complained to Elections Canada about repeated calls, purporting to be from the Liberals, pestering Jewish voters on the Sabbath. This, Volpe said at the time, was "a classic vote suppression technique," designed to antagonise Liberal supporters. Elections Canada responded that it had no jurisdiction to investigate where there was no evidence of "false pretence." The Liberals insist there was.

In addition, on election day, Elections Canada workers reported dozens of complaints from voters who had been told, wrongly, that their polling place had been changed. That sounds very much like the "misdirection" calls that were reported from all over the country — targeting voters who had revealed they did not plan to vote Conservative.

After the election, though, the question of special ballots took on a life of its own in Eglinton Lawrence. It emerged that an unusually high number of special ballots — as many as 2,700 — had been applied for and granted. That could reflect a strong get-out-the-vote effort by all parties in a heated contest — but the effort by supporters of Joe Oliver stood out.

'Harper stands for us'

In particular, the Liberals point to an "open letter to the community" by a Jewish group called "Gesher," meaning bridge. The letter urged readers to vote for Oliver and to make sure their families and friends did the same.

"Harper stands for us, we must stand for him," the flyer says. "Every vote counts."

The Gesher letter notes that many families would be visiting for Passover at the time of the election and adds, "Canadian citizens who live in other countries can vote in this election. Please ensure that family members visiting for Yom Tov (Passover) go to vote."

The flyer was correct up to a point: non-resident citizens can vote if they have been away from Canada for less than five years and intend to return. And many residents, too, could vote by special ballot if they planned to be away when the voting began.

In the end, many hundreds of Jewish voters — and hundreds of others — did obtain special ballots in Eglinton Lawrence. We don't know how they voted. But we do know that the paperwork was not exactly meticulous.

CBC News has examined more than a thousand of the forms filled in to register and to obtain special ballots in Eglinton Lawrence during the 2011 election. Of those, only a few seem to be filled out completely and correctly, according to the rules laid out by Elections Canada in its "Special Ballot Coordinator's Manual."

These specify, for example that a residential address, not merely a mailing address, is essential. The application form must be "fully and accurately completed," the manual says, and ID must be checked in every case.

Even so, hundreds of the special ballot forms are incomplete. Some show no residential address, or no address at all. Many also say the voter is not on the voters list. In at least 150 cases, there is no residential address on forms which also fail to show whether the voters are on the list — or say they're not. Others give no date of birth — which is not optional, under the rules — or give an address which turns out to be problematic. One gives the address of a UPS store on Eglinton Avenue. Nobody lives there.

In a couple of cases, there is no address of any kind — mailing, residential or previous. On each of those, the applicant also says they're not on the voters list. But all of them were approved, as shown by the "signature of authorized officer" on the bottom line.

What to make of these? Basically, we just have to hope that the ballot officer checked every voter's ID and didn't bother about whether the form was properly completed. Perhaps there was a line-up and the officer wanted to move things along. But how did they check the ID to see if it matched an address which ... was not provided?

What's clear is that Elections Canada staff were definitely not obstructing the vote with red tape.

How can Elections Canada investigate if nobody hands over the evidence?

None of this proves that the Liberals were robbed, either in Eglinton Lawrence or Etobicoke Centre. Even if they were, the problem is bureaucratic sloppiness, not chicanery by their rivals. However, not surprisingly, Elections Canada officials seem much keener to investigate issues like robocalls — where no-one's blaming Elections Canada — than their own mistakes.

Appearing before a parliamentary committee, Chief Electoral Officer Marc Mayrand, objected to "sweeping and vague allegations of irregularities being made public many months after the election and not supported by specific facts."

Mayrand added that, "In some cases, the complaints are made to the media without any information being forwarded to Elections Canada. Such allegations cannot be verified." He was referring in part, he said, to the case of Eglinton Lawrence, noting that "no specific actionable information has been provided to us, making any kind of review challenging, to say the least."

What is striking about these comments is that, in truth, getting the evidence was not challenging at all. That's because the special ballot forms were all provided to Elections Canada, by its own officials, immediately after the election. The same is true in every riding. By definition, all those forms belong to Elections Canada, and have been in its possession ever since.

Equally striking is that, in the next breath, Mayrand testified that he had, in fact, reviewed the very forms which, supposedly, had not been provided by the irresponsible authors of the unverifiable allegations.

"To be diligent," he went on, "we examined all 1,275 of these forms, and, with the exception of three voters who were listed at a commercial address, could not find any evidence of irregularities as claimed."

Presumably, this means that missing addresses or dates of birth, on applications by people who say they are not on the voters list, don't qualify as "irregularities." In which case, errors are not only "common" and "inevitable," but uncounted.

Of course, Mayrand also noted that the robocall scandal is far more serious. "Outrageous," he called it — and who could argue? By comparison, even hundreds of incomplete special ballot forms don't stack up.

Then again, they do stack up a little too high for comfort. In a country where you don't even have to prove citizenship to be handed a ballot, it couldn't hurt to make sure that voters at least provide an address.