Life on streets 'a killer': New hospice offers end-of-life care to the homeless

Toronto's Journey Home Hospice offers palliative care, support to people with nobody to turn to

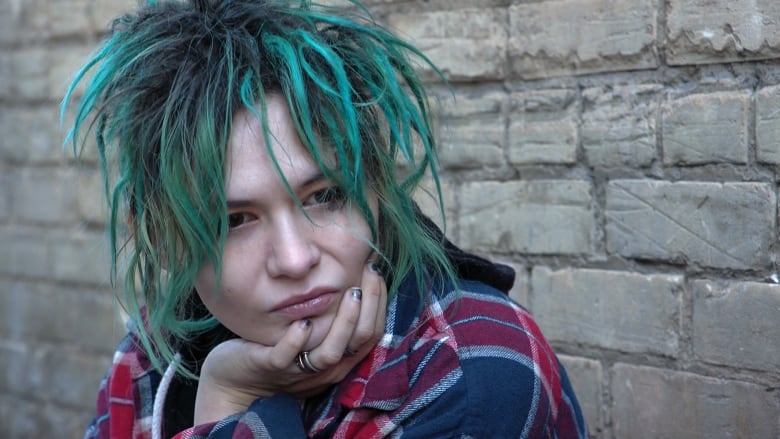

Pandora was raped at 15 and, ashamed to face her father, never went home again. Living on the streets, she struggled with mental health and addiction issues — and a medical condition that has been slowly killing her.

Pandora was dying, homeless and alone.

Then Dr. Naheed Dosani and a team setting up the new Journey Home Hospice stepped in.

"It means a lot. It means a lot," Pandora said of her move to the palliative care facility, the first of its kind in Canada for the homeless. "It means quality of life is real and that I can experience it."

Dosani is part of Palliative Education and Care for the Homeless (PEACH), a mobile medical team in Toronto. His job is to treat the community of people living on the streets, wherever they may be in the city.

-

WATCH: The National's feature on Dr. Dosani and Journey Home Hospice on Monday evening on CBC Television and streamed online

On any given night, he said 5,200 people are sleeping on the streets in Toronto. For every one of those, 23 other people are in temporary housing — anything from couch surfing and staying with friends to living in shelters.

It's a reality he said most people aren't even aware of.

"I think about how a city like this can look, like everyone's really well supported, and really, it appears that way," Dosani said. "But there are so many people falling through the in-betweens, falling through the cracks. And it's this invisible sense of vulnerability, it's hidden to the naked eye, which is dangerous."

Healing on the streets

Dosani's day typically starts with a call from a social worker or a shelter telling him of a homeless person who needs medical attention.

Often he meets his patients in public parks, alleys or under the bridges where they live. No two days are ever the same and there's no guarantee that the people he sees will come back for followup care.

Just by virtue of being homeless, Dosani said the health of his patients is significantly compromised. Compared to the general population, homeless people are:

- Four times more likely to have cancer.

- Five times more likely to have heart disease.

- Twenty-eight times more likely to have Hepatitis C.

The average life expectancy of a person living on the streets in Canada is 47.

"When we're going out, we try to recognize the trauma these people have experienced," Dosani explained.

"By and large, if you approach people in a very humane way, while recognizing the privilege we have as health-care providers when we step into that space, we build that rapport. We can build that trust."

Dosani, who often lectures around the city on the need to medically support Toronto's homeless population, recently caught the attention of Nancy Lefebre from Saint Elizabeth's Health Care.

Lefebre approached him with the idea to open a palliative care hospice for Toronto's homeless — a place where the very ill could spend their final days in comfort.

Lefebre, Dosani and their organizations teamed up with Toronto Hospice and Inner City Health Associates (the group behind PEACH) — and this spring, the Journey Home Hospice opened with four beds at 90 Shuter St. They were inspired by The Ottawa Mission, a hospice in the nation's capital that began as a mission and expanded to also provide palliative care to the homeless.

The government funds 50 per cent of the Journey Home Hospice's budget, but the group still needs to raise millions to cover the rest of the annual operating costs.

"We have a whole army of people working behind the scenes to make this happen," said Lefebre, who started out her career as a street nurse in Vancouver.

"I hope that this will be a warm, supportive, safe environment for people who do not have a home, where they can come and live their life until they die with dignity."

A place for Pandora

Pandora, 23, had a rocky relationship with her father as a teen. After she was date-raped, she said she couldn't face going home.

Life on the streets was tough enough, and Pandora found herself living on park benches and under bridges. Then she developed a serious heart condition, which made her situation even more dire.

"It wasn't necessarily being homeless that was terrifying; it was what could happen when I was homeless that was the scariest," she said.

Dosani met Pandora in the spring through her caseworker and started visiting her at a temporary shelter.

"She's in a very difficult scenario, because she's dealing with a very significant heart issue, a vegetation called Infective Endocarditis [caused by a bacterial or fungal infection]," Dosani told CBC News in an interview in May.

"And unfortunately, the treatment that she would need, a particular type of surgery, she's not deemed a candidate for."

Living on the streets and in shelters, it was hard for Pandora to get regular care. She often went without the oxygen she needed to treat her condition because shelters could not accommodate the necessary equipment.

Dosani said Pandora's medical situation reached a critical point recently, and there was little that could be done for her on the streets.

But he did have a way to help provide some comfort. She was one of the first patients to be offered a room at Journey Home Hospice in May after it opened.

At the new hospice, Pandora would have a private room and washroom, 24-hour medical care and three meals a day, as well as counselling and a place for her family or friends to visit her — all in an environment that looks much more like a home than a hospital.

When she was told she had a room at the hospice, Pandora was immediately hopeful that the move could lead to a reunion with her parents.

"It's giving them a place to send a card to — you know, an address," she said. "That makes a huge difference. It's them being able to know that I'm not dead, that I exist. That I'm not dead because I'm somewhere, that I still take up space."

Tragically, her time at Journey Home Hospice was short ��— Pandora died just two days after moving into her room.

Dosani described Pandora's joy at having a place of her own, but also the shock he and the home's team felt at her sudden passing.

"When she moved in, her eyes lit up, she was bright, she was home, and she even said that to us," he said.

"One has to wonder what could have been possible had there been a place like Journey Home Hospice she could have called home earlier," he added.

"These are the kinds of questions that keep me up at night thinking about Pandora or other clients."

It's those kinds of questions that Dosani says motivates him to continue working on the streets, trying to find people who need care and referring those at the end of life to Journey Home Hospice.

Unfortunately, there's no shortage of homeless people in need of palliative care.

"Homelessness is worse than any kind of chronic disease," Lefebre said. "It's a killer … it certainly cuts a lifespan in half. So, yes, we will have a long wait list, which is sad to say."

The demand is so great that Journey Home Hospice is already aiming to expand. By 2019, it plans to more than double its space to 10 beds.

"If we really can't get what a human life is worth at the end of life for people who are most vulnerable and most marginalized, I don't know what we are doing," Dosani said.

"But it's possible. There is community, there's compassion, people do care. And the opening of Journey Home Hospice is a testament to that."

-

WATCH: The National's feature on Dr. Dosani and Journey Home Hospice on Monday evening on CBC Television and streamed online