Feeling 'sliced up inside': Birth control implant Essure led to pain, serious problems for some women

Any side-effects reported about sterilization device weren’t made public by Health Canada

After having two sons, 39-year-old Trisha Travis and her husband decided that their family was complete. They were ready for permanent birth control.

Travis, of Weyburn, Sask., always thought there was only one method of sterilization. As her own mother had done, she would have surgery to have her tubes tied.

But when her doctor told Travis about Essure, a birth control device that would be implanted for life, the busy mother was sold.

In October 2014, Travis had Essure inserted. But days later, her health started to decline, launching her into two years of physical and emotional pain, with problems including heavy bleeding and backaches.

Essure was pitched to Travis and about 10,000 other Canadian women who opted for it as a non-surgical, non-invasive sterilization procedure. It would be done in the doctor's office within 15 minutes.

"That was what sounded good to me," said Travis. "I just expected that it would be quick and I wouldn't have to take a lot of time off work and I'd be home with my kids."

Doctors and the company that manufactured Essure claimed it was a safe and easy option compared to tubal ligation.

- Watch "Unreported: The Essure Story" on The Fifth Estate on CBC-TV Sunday at 9 p.m.

But for Travis and hundreds of other Canadian women, the experience with the device has been anything but easy.

A CBC News/Fifth Estate investigation found that a lack of detailed information about Essure and the adverse reactions women were having to it put some women's health in jeopardy.

The investigation also found that Health Canada, which is responsible for the regulation of medical devices, hasn't been transparent about Essure's licencing or reporting of problems with the implant.

'Sweating and shaking'

Essure was made and marketed by a small American company called Conceptus Inc., and then sold to Bayer in 2013. It was designed to work by inserting a two-centimetre coil into each fallopian tube. Scar tissue would form around the coil, closing off the tubes and preventing sperm from meeting an egg.

Immediately after her procedure in 2014, Travis had relentless backaches, cramping, rashes and constant bleeding.

"I would just be sweating and shaking because the pain was so bad."

Travis said she constantly had blood clots. One day during her shift at the nursing home where she worked, a clot the size of a baseball fell onto the dining room floor.

"Or you would just be pushed on to someone else who didn't ever find out what was wrong."

The constant bleeding continued. A procedure to try to stop it didn't work either.

When doctors realized the bleeding wasn't menstrual, Travis was told in 2015 that she needed an emergency hysterectomy.

I was sad but it's like I just needed it to be over.- Trisha Travis,

As it turns out, her uterus had been punctured during the Essure implant, causing the bleeding. She says her doctor never told her about the puncture.

Her ordeal spanned two years and although she didn't expect to have a hysterectomy, she was relieved that it would eliminate the pain.

"I was sad but it's like I just needed it to be over."

Lack of reporting

Travis wasn't alone in her struggles with Essure, but she had no way of knowing.

Health Canada, which approved Essure in 2001, maintains an online registry where patients and doctors can report complications. However, only manufacturers and importers are mandated to report what they refer to as "adverse events."

And no one would have found anything online from Health Canada about problems because adverse events aren't made public.

The data related to Essure revealed that in the first 12 years of being licensed, Health Canada received one report.

Since 2013, 84 complications have been flagged to Health Canada. Of that total, 68 reports were provided by the manufacturer and the rest were from doctors and patients.

But those numbers don't reflect the hundreds of women in Canada who have complained about issues with Essure by joining lawsuits or banding together on social media. As of October 2018 in the U.S., about 18,000 women have filed lawsuits against Bayer.

John Thiel, the provincial head of the department of obstetrics, gynecology and reproductive sciences in the college of medicine at the University of Saskatchewan, was one of the first doctors to bring Essure to Canada.

He's performed about 2,000 implants and has trained other physicians on how to insert the coils. He also sits on a medical advisory board for Bayer and is listed as a consultant for the manufacturer on two of his nine published academic articles about the device.

"It's safer, it's more reliable. There are fewer failures associated with it," Thiel told CBC News in 2007.

We never submitted anything to Health Canada on any adverse event.- John Thiel

But when a patient returned to Thiel with concerns after getting Essure, Thiel said his office didn't immediately assume that Essure was the cause.

"That's much like saying: 'I got a flu shot, I got sick a week later and it was my flu shot that caused it.' Probably not," Thiel told The Fifth Estate in November.

Since Essure came on the market in 2002, Thiel said he hasn't reported any complications.

As for reporting to the manufacturer, he said that it "would be such a gross violation of a patient's confidentiality to discuss an adverse event with a company."

He would only report adverse events to the manufacturer if the women were involved in a study he was working on where he was obliged to report.

In a Nov. 23 statement to CBC News, Bayer Canada says the company "encourages all patients and health-care professionals to report any adverse events with any of our products."

"We also want to make sure that institutions will have to report to Health Canada if there's any side-effects or any issues related to medical devices," Petipas Taylor told CBC News Friday.

"We want to expand that and we want to make sure that hospitals will have to report that information to Health Canada. And also I want to create a process that patients will also be able to make that report to Health Canada."

The statements come on the heels of a global media collaboration involving Radio-Canada, the Toronto Star and the Washington-based International Consortium of Investigative Journalists that examined tens of thousands of medical devices and how they're made, approved and monitored by regulators worldwide.

Making it to market

Health Canada won't disclose the clinical evidence it based its approval of Essure on, but the agency says it's working towards being more open.

In a Nov. 27 statement to The Fifth Estate, Health Canada says it "strongly believes in transparency and that increasing Canadians' access to clinical data can have widespread benefits throughout the health-care system."

In the next few months, the agency says new regulations are expected to come into effect to allow public access to this data.

During a day-long panel in 2002, the company that made Essure presented findings from its clinical trials. It assured panel members that the coils worked in preventing women from becoming pregnant and did not seem to cause complications.

The majority of panelists concluded the benefits of Essure would likely outweigh the risks and Essure got its approval.

- The Implant Files: Read all our coverage on medical devices

The company provided the FDA with an overview of the four clinical trials that followed fewer than 1,000 women — and only 25 per cent were followed for more than a year.

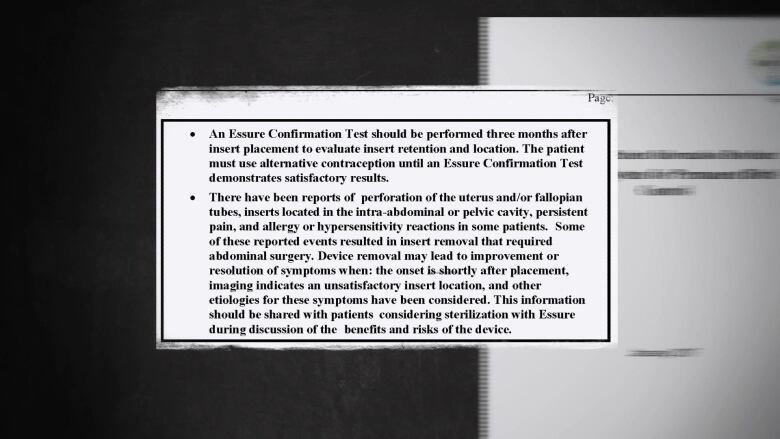

Complaints against Essure mounted in the U.S. and in 2015 the same FDA panel that originally approved the device reconvened and took another look. That resulted in a new "black box" warning label and a lengthy checklist doctors are required to go over with patients before implanting the device.

Canada followed suit.

In May 2016, Health Canada released a public safety alert, saying that complications with the device include changes in menstrual bleeding, unintended pregnancy, chronic pain, perforation and migration of the device, allergy and sensitivity or immune-type reactions.

"Some complications may be considered serious," said the agency. "These complications have led to the surgical removal of Essure, which may include hysterectomy."

In January 2017, Bayer issued a communication, verified by Health Canada, to provide updated labelling, including revised instructions for use, and introduced a patient information brochure that included a patient-doctor discussion checklist.

It makes me wonder if we could have had a little bit longer followup or a larger number of women.- Dr. Sanket Dhruva

After hearing of the FDA panel reassembling, Dr. Sanket Dhruva, a cardiologist and assistant professor at the University of California, decided to re-examine the company's trial data that it originally presented to the FDA in 2002. His findings were published in a 2015 New England Journal of Medicine paper.

"In general we found that the approval of the device was based on evidence that may have been incomplete and lacked complete followup of women who had been implanted with the device," Dhruva told CBC News.

"It makes me wonder if we could have had a little bit longer followup or a larger number of women."

Bayer stands by its product, saying women with Essure in place can continue to use the device.

"The benefit-risk profile of Essure remains unchanged," Bayer Canada said in a statement to The Fifth Estate last month.

It got to the point where I was stuck either on the couch or in fetal position on my bed.- Keri Ponace

As of October, about 500 Canadian women claiming issues with Essure have registered with a class-action lawsuit that's waiting certification expected next year.

Growing support

About one million women worldwide have had Essure implanted, according to data from the ICIJ.

Women having issues with Essure eventually found each other online and in Facebook groups.

They talked about their symptoms of severe bloating, fatigue, hair loss, itchy skin, extreme bleeding, clots and debilitating pain, among many others. Being allergic to nickel, which the coils contain, also seemed to be an issue.

Keri Ponace, 40, of Regina found comfort and some crucial advice in one of those online groups.

In 2012, she wasn't sure if she wanted to try again one day to have another baby, but she was looking for birth control. She took her doctor's advice and had Essure implanted.

"It got to the point where I was stuck either on the couch or in fetal position on my bed."

She went back to her doctor, but didn't receive any help.

"He said it's all in my head, that I'm thinking that there's pain there when there shouldn't be because the coils were in place," said Ponace.

Advice from others

Learning of other women's stories on social media convinced Ponace she wanted Essure out of her body. In 2016, she convinced her doctor to remove her tubes containing the coils, but that didn't relieve the pain.

"It's like I have two screwdrivers drilling me in the sides of my hips … or somebody just took a knife and pushed it and twisted it."

As it turns out, Ponace has a one-millimetre metal particle left from Essure that is lodged in her uterus.

"I feel like I'm getting literally sliced up inside when I get up and I sit down and when I'm moving around."

But removing those fragments can be difficult and can require a hysterectomy, says an Illinois doctor.

"Patients have gotten to a point where they're so frustrated [with] all the pain and problems they've had and seeing doctors that won't listen to them that they're actually happy when they have their hysterectomies because they feel better," said Cassidy.

Ponace faces the same outcome because she said her doctor wouldn't be able to go in and take the fragment alone as a result of where it's lodged in her uterus.

"I feel like my womanhood has literally been ripped away," said Ponace. "This stuff shouldn't have to happen all because I wanted birth control."