Help wanted: Women in Windsor face additional challenges in COVID-19 'she-cession'

'Women have been front lined and sidelined by this pandemic'

Derric'Ka Talbot finally thought her career was moving in the right direction, when all of a sudden it felt like her life had been "put on pause."

The 26-year-old was working as an apprentice millwright through an earn-while-you-learn program at St. Clair College, hoping to move away from her primary job as a personal support worker (PSW).

Then the pandemic hit and everything fell apart. She went from working two jobs to none.

Her apprenticeship ended prematurely and she was forced to quit being a PSW to care for her 4-year-old son, who was suddenly without daycare.

Living with her 75-year-old grandmother also made Talbot worry that she might bring the virus home.

Talbot is one of 1.5 million Canadian women who became a casualty of what's been dubbed COVID-19's "she-cession." A lack of childcare and pandemic shut-downs hitting female-dominated sectors combined to force women out of the workforce. And in Windsor, where the economy depends on a typically male-dominated manufacturing sector and historically female-led tourism, retail and food sectors, Talbot wasn't the only local woman to find herself unemployed.

"It's tough … it's a sticky situation for women out there. I feel like you're just damned if you do and damned if you don't. And it's just difficult to make any decision right now at all, no one knows what's going on, no one knows what's happening," Talbot said.

"You're trying to do what's best for your children, yet keep a roof over your head."

She-cession disproportionately impacts working women

The recession sparked by the pandemic put thousands out of work, but it disproportionately affected women.

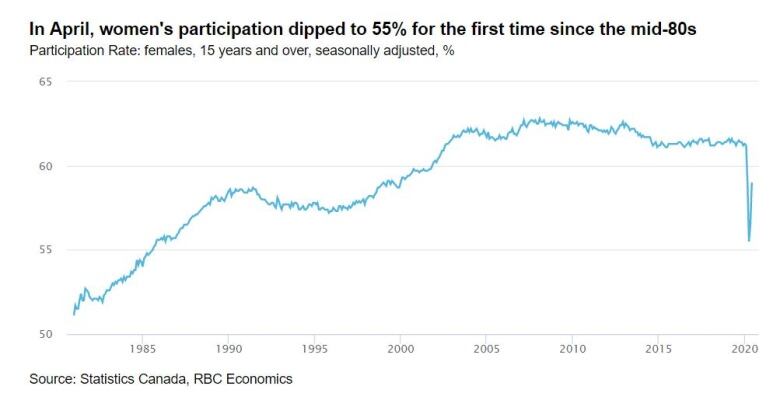

A July report from RBC Economics called the hit on women's employment "unprecedented," noting that in April, women's participation in the Canadian workforce fell to 55 per cent — a level last seen in 1986.

In Windsor, that economic hit was especially felt by women, who already have the odds stacked against them.

Windsor 6th lowest on best Canadian cities for women

In 2019's Best and Worst Cities to be a Woman in Canada report, Windsor placed 20 out of 26 cities.

The report looks at the gender gap in areas such as education, poverty and income.

Author of the report, Katherine Scott, a senior researcher with the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives in Ottawa, said on average, women in Windsor earn less, have lower levels of employment and have experienced rates of poverty higher than the national average.

"It's shaping up to be a huge economic challenge for women. It'll be really hard in a community like Windsor where women already had relatively lower incomes to start with," she said.

Scott also mentioned data from Statistics Canada that shows in 2018, Windsor had the fourth highest rate of female poverty in the country.

This alone, she said, paints a "picture of considerable challenge" for women locally.

Data from the 2016 census shows that the Windsor areas has more than 14,000 single moms. And according to a United Way cost of poverty report from 2014, some 42 per cent live in poverty.

'Front lined and sidelined' by pandemic

In the past few years, Scott said, Windsor-Essex was actually seeing a narrowing of its gender employment gap, but that's now increasing across the region and the rest of Canada.

But Scott says it's "especially troubling" for Windsor, where women's employment is typically lower than other Canadian cities.

"We know that women have been front-lined and sidelined by this pandemic and by that I mean certainly large numbers of women of course are essential workers working on the frontlines, whether it's in our hospitals, community services or whether it's in retail and the like," she said.

One of those pushed to the sidelines was Maryam Malih, who had just landed her dream placement at a spa in Windsor.

She said she was promised full-time work at the company, until COVID-19 arrived.

"During my placement, everything was going fine. But at the very end of my placement, that's when COVID hit and because of that, I was laid off," Malih said. "She lost a lot of business, the owner, she couldn't take me back."

"I was going to practice there and maybe get more experience so I could go to the school maybe there or open my own business. But now that I don't have the training because I got laid off, I can't really do any of that now."

Unable to find a job elsewhere, Malih said she plans on going back to school.

As economy reopens, region far from being in the clear

As more businesses reopen in Stage 3, the unemployment rate among women is slowly improving.

But, manager of projects and research for Workforce WindsorEssex, Tashlyn Teskey said it's still a far-cry from where it was last year.

In 2020, women's unemployment in Windsor peaked in May at 14.7 per cent. As of September, it dropped to 12.1 per cent, but it's still about five per cent higher than the same time last year, Teskey said.

"So we're not quite at pre-COVID levels, but we're working in the right direction," she said, adding that she's still concerned things might get worse again before they get better.

"With many working in the tourism or restaurant industry, as we move into winter, a lot of those restaurants are going to be pulling back their capacity with patios closing and delivery possibly being limited by weather ... we might see kind of a return to lower capacity and potentially more layoffs as they move out of their peak season again," she said.

Affordable and accessible childcare needed

Moving forward, Scott said a key factor in getting women back in the workforce is affordable and accessible childcare.

"We have to focus on those who are disproportionately impacted and in doing that, we raise the bar for everyone," Scott said.

As for Talbot, when she exhausted the Canadian Emergency Response Benefit, she knew she had to get back in to the workforce.

So, she compromised — she's a part-time PSW so she can still care for her son.