Mothers send pictures of fentanyl victims to Justin Trudeau

Awareness campaign Moms Stop The Harm aims to show human side of Canada's opioid crisis

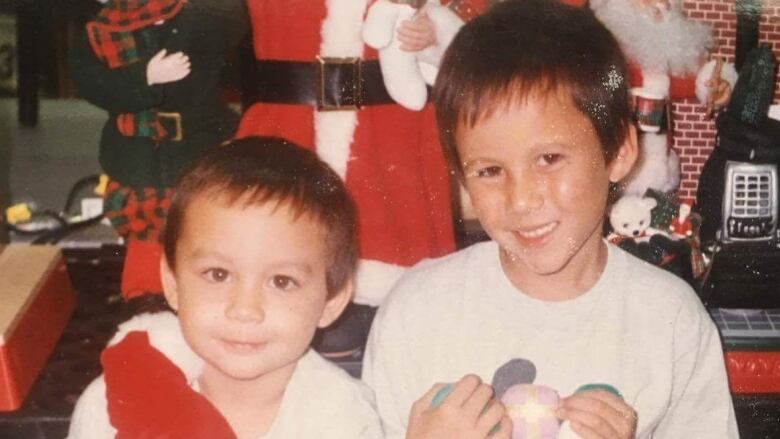

When Irene Paterson's son Roger Wong didn't show up for a baseball game the two had planned to attend in June, she became worried.

She eventually went to the police station with a friend of Wong's to report him missing.

A policeman "took us into a room and said, 'I can tell you that your son is dead,' Paterson recalled.

Wong died from a fentanyl overdose in a downtown parking lot.

"That was the moment my life ended," the Toronto mom said.

Now, his 61-year-old mother is joining a campaign called Moms Stop The Harm to raise awareness about Canada's opioid crisis because "my son is not a statistic," she wrote in an email.

The group sends pictures of the loved ones they've lost to the prime minister in an attempt to show the human side of the opioid crisis.

- Why this grieving father wants politicians to know that fentanyl killed his son

- Fighting the fentanyl crisis with new technology

"Every day you see the statistics and all of that, but I just thought people should see what's left behind: the devastation, friends, loved ones, people that loved him," she said.

About 500 moms so far have sent in portraits asking the government to increase resources to fight fentanyl addiction.

'Compassion instead of judgement'

Tara Gomes, a drug policy research scientist at St. Michael's Hospital, says this initiative by the mothers is an "important and brave" step in fighting overdoses.

The biggest hurdle to battling the crisis, she says, is stigma.

"A lot of people are not appreciating that everyone who dies from or are affected by overdoses are friends, family members. They have parents, they have children. It doesn't just impact their lives, it affects all of our society," Gomes told CBC Toronto.

"Governments are starting to understand that this is a mental issue and not some shortfall in a few people lives," she said. "We need to make sure enough resources are going towards it to make sure we treat people with opioid addiction with compassion and respect instead of with judgement."

She wants resources to be directed towards supervised injection sites and controlled substance use to first curb the number of Canadians dying from opioid overdoses. Then, she says, the government and the health community can address the issue with a long-term lens.

For Paterson, it's too late for her son but maybe not for someone else's child.

"Roger's gone. There is nothing I can do to bring him back, but I can help someone else. Together, we can help somebody else's someone. Even just one," she said.

With files from Lisa Xing