Look out N95. A group from the U of S is engineering a new mask

It's estimated the prototype is a month away from Health Canada approval and rollout in Sask. hospitals

Erik Olson has a stack of faulty pseudo-N95 respirator masks stacked in a corner in his parents' home in Saskatoon.

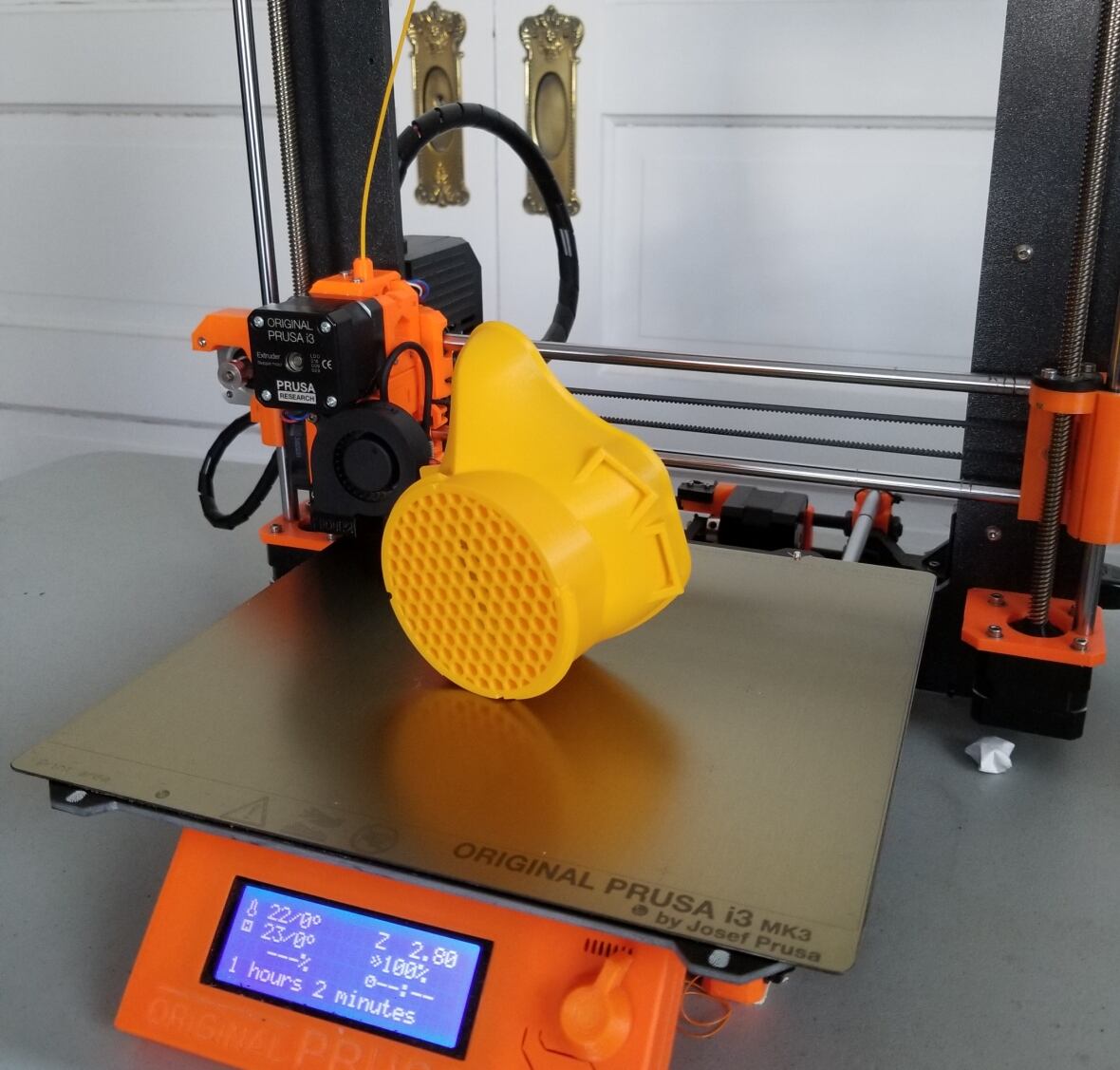

The stack is evidence of a man's quest to create a 3D printed face mask that meets all the qualifications of the N95, a designation that specifically refers to the masks' ability to filter out 95 per cent of particulate matter.

The mask shells — which range in appearance from looking like a gas mask to a duck bill — are all produced by Olson.

The first of the bunch he describes as a "crude, trapezoid-shaped monstrosity" made out of plastic that dug heavily into some parts of the face and didn't make contact at all with other parts.

From there, the stack shows how the trapezoid shape morphed into something more nuanced, a more detailed nosepiece and a shape that better fits the natural contours of the face.

"My personal experience with this, comparing to N95-like masks I've either had to wear working on the farm or working in animal care at the university is that it is as or more comfortable, in my opinion," Olson said.

Olson is on a team of College of Engineering grad students and staff at the University of Saskatchewan that is trying to create a new reusable medical mask in an effort to reduce the global shortage of N95 respirators.

The team is collaborating with the Saskatchewan Health Authority.

The team isn't there yet — the mask design it's come up with is being tested under what the university called a "rigorous process" to meet Health Canada's approval, and it's estimated it will be a month before the approval goes through.

The prototype Olson and his colleagues have come up with, which they are calling the USask Mask has already been tested at the University Hospital along with another 3D printable mask that has gained popularity, called the Montana Mask.

Initial results didn't cut the mustard, but Olson said testing processes are designed for the traditional N95s and don't seem to work accurately with the new type of respiratory mask.

In his view, it does seal well and is effective but they need to refine testing methods to prove that.

Olson is the main test subject for now.

"The main challenge now will be trying to tweak the design so that it doesn't just work well for just a couple of people who have such-and-such a nose geometry or what have you but works well for just about anyone," he said.

Addressing worldwide shortages in their own backyard

Traditional N95s have been hard to come by, and at times healthcare workers in the province have found themselves limited to how many they can use in a day, according to the Sask. Union of Nurses.

Those shortages are why, back in late March when staff and students at the University of Saskatchewan were dealing with the campus being locked down and classes cancelled, engineering professor James Johnston sent out emails seeking a crew to come up with a prototype.

The prototype would be an alternative to the N95 respirator as it currently exists.

And so Olson, who already had a 3D printer handy, and his colleagues — who wore masks and gloves to retrieve the university's 3D printers and take them home — got started.

Olson said they had three key priorities for the respirator: 1.) it sits well on the face and is comfortable, 2.) it has a large area for the filter so that a person can breathe easily while wearing it, 3.) it's easy to make using a 3D printer and easy to assemble.

The aim is to be able to manufacture 60 masks a day using USask 3D printers.

The design includes some unexpected materials: weather stripping, the kind you can buy at a local hardware shop, provides some give and a foamy texture so the mask can fit differently shaped faces, and vacuum bags cut into a circle filter the incoming particles.

The team started off by 3D printing existing designs on the internet. Those didn't fit the team's criteria so they started designing their own.

Olson says there's a beauty to how far 3D printing technology has come — that he can walk over to his family's living room with a memory card of the design and have a mask within hours.

"There's a certain level of of fun in being able to conjure something up from the ether and within so many hours just have it sitting in front of you on a table," he said.

To liven things up, he has taken to printing the masks off in different colours.

While there are lulls when the masks are printing, he said working with such a purpose-driven team has reminded him why he went into engineering in the first place: "engineers, we're kind of problem-solving junkies."

For Olson, the trial and error process included the realization that the variation of people's nose shapes is the biggest challenge with mask making.

He took inspiration from his mother's CPAP mask, which is used to help people with sleep apnea get oxygen at night.

The prototype as it stands today will be tweaked a bit over the coming weeks — all by people who are doing their work from home — and is adaptable to new materials.

The final design will be posted online once completed so others can produce the masks and potentially improve it.

The open source nature of the project means that people elsewhere can combine forces to address the fear health-care workers in the United States have of mask supplies running out, engineering professor Johnston said in a university news release.

"It's not really important whose design it is in the end, just that it works," Johnston said.

In the release, he said cloth masks may not be effective against the tiny size of the virus. Even before approval goes through, Olson said it's possible that the group will distribute masks to the general public.

How does Olson feel about the idea that the project will help humankind?

"That would be delightful, almost unimaginably so. The idea of not just getting to solve a problem but getting to solve a problem that's so near and dear to helping and protecting a lot of people is a real privilege," he said.

As for what Olson is doing with the masks he's accumulated, he's hanging onto them for now.

With files from CBC Saskatoon Morning and Morning Edition