'That's not going to change anything': Why Sask. coroner's inquests leave people wanting more

Costs for death inquests are rising, effectiveness is being questioned

Saskatchewan coroner's inquests are leaving participants dissatisfied and sparking questions about whether the process brings about any change.

Meanwhile, the cost of inquests is rising. In 2013-14, the average cost of an inquest held by the Saskatchewan Coroners Service (SCS) was $16,800. In 2017-18 the average was $29,300.

"Inquests are becoming more complex and time consuming," wrote former Saskatoon police chief Clive Weighill in a review of the service, just months before he took over as the province's new chief coroner.

Weighill cited several reasons for the increase, including "longer questioning and cross examination of witnesses" and lawyers treating inquests like criminal trials.

Despite the increased cost and effort, inquests are leaving some participants feeling shortchanged.

"I was torn up. I wasn't happy at all walking out of there," said Charmaine Dreaver of her recent inquest experience.

Dreaver's son, 22-year-old Jordan Lafond, was involved in a police chase in Saskatoon. The stolen truck Lafond was in crashed into a fence, ejecting him from the vehicle. He later died.

A forensic pathologist testified that the impact of the crash was a major factor in Lafond's death. The six-person inquest jury also heard a police officer admit he repeatedly kneed Lafond in the head after the crash because he thought Lafond was resisting arrest.

Exactly what killed Lafond remained unclear, but neither of the jury's two recommendations this past summer focused on police conduct. Instead, the jury stressed the need to educate people about the safe storage of guns. Police had testified they were concerned about a high-powered gun inside the truck.

"That's not going to change anything with what happened to my son," said Dreaver of the recommendations from the week-long inquest.

Chris Murphy, the lawyer who represented Lafond's family, said they "didn't want to find out fault, but at the same time, we wanted to get to the bottom of what happened."

That was made difficult by the narrow scope of what inquest juries are allowed to rule on, said Murphy.

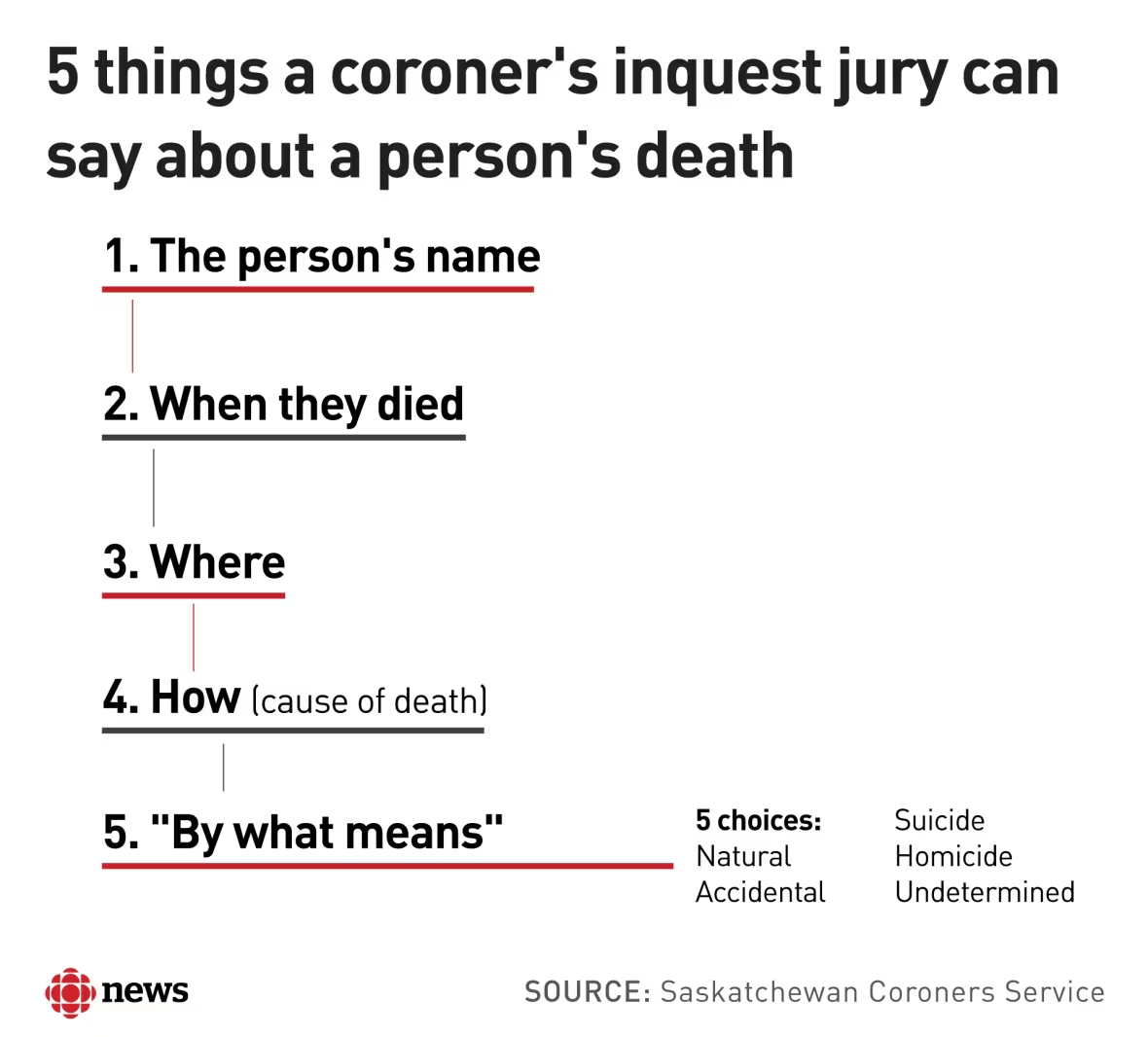

Coroner's inquests limit juries to ruling on "how, when, where and by what means" a person died, while their recommendations are strictly meant to prevent similar deaths.

Weighing in on Saskatoon police officers' conduct just wasn't on the table, Murphy said.

"From the perspective of the family, you go through this and you don't really get the answers that you want," he said.

'Role of an inquest is often confused'

Coroner's inquests are not meant to assign legal responsibility for a death. No one is on trial.

Many people still think otherwise, said Brian Pfefferle, a Saskatoon defence attorney.

"It's still remarkable the number of people that will review whatever's online about these things but say 'Why can't this person be charged criminally?' " he said.

Weighill agreed that people sometimes don't understand the process.

"The role of an inquest is often confused by the family and the public who are looking for answers surrounding the death and are seeking to find a person or persons at fault," he wrote.

An upcoming inquest into the death of Brydon Whitstone faces similar expectations.

Beginning December 3, a six-person jury will hear details about how the 22-year-old man was shot and killed by an RCMP officer in North Battleford last year.

-

'I want answers': Mother of man fatally shot 1 year ago by Sask. RCMP feasts and waits for inquest

-

Prominent Cree lawyer Don Worme's firm representing Brydon Whitstone family in RCMP shooting inquest

Up to now, authorities have offered few details about the altercation, though Saskatchewan prosecutors recently decided the officer's actions did not call for criminal charges.

Asked about the inquest, Whitstone's mother Dorothy Laboucane said, "I just hope everything will work out, that we'll get justice."

'Gathering dust in a filing cabinet'

Weighill's report on the SCS didn't make any specific suggestion for how to combat the perception that inquests are criminal processes. He did recommend hiring a family advocate to answer families' questions about the inquest process.

Another change he proposed went into effect even before he started his new job last September. Inquest juries' recommendations and how groups respond to them are now posted online, something most other coroners services do.

-

Incoming Sask. coroner Clive Weighill flags potential changes to death inquests

-

New Sask. chief coroner Clive Weighill says dealing with toxicology delays a top priority

Ron Piche, the lawyer who originally represented Whitstone's family, said inquest participants have been candid with him about where they think jury recommendations end up.

"Gathering dust in a filing cabinet somewhere," he said. "If I were to wager a guess, I'd suggest that very few of them get implemented."

Delayed response tragic: lawyer

CBC News has reviewed all the recommendations made by Saskatchewan coroner's inquest juries from 2014 to November 2018, plus the responses filed by the agencies to whom the recommendations were made.

One high-profile case still hasn't received a response from a key party.

Nadine Machiskinic, 29, was an Indigenous mother of four who died in 2015 after she fell 10 storeys down a laundry chute at Regina's Delta Hotel.

The inquest jury's sole but sweeping recommendation, directed to "all hotels," was that "any service chutes should be locked and only accessible by staff."

A combined four hotels in Saskatoon and Regina responded, some just to say that their buildings don't have chutes.

More than 18 months later, the Ministry of Justice says the SCS has not received a response from the Regina Delta where Machiskinic was injured.

"The SCS has posted all responses received to date," said a spokesperson, adding that the coroners service reminds groups that don't respond within six months.

Beyond that, "If the SCS does not receive a response, the responsibility remains with the affected agency to explain why the recommendations have not been responded to," the spokesperson said.

Just as inquest jury recommendations are not legally binding, groups aren't legally required to respond them.

"There's nothing saying there has to be a response," said lawyer Ammy Murray, adding, "Maybe there should be some kind of ongoing follow-through."

CBC News has reached out to Marriott Canada, the owner of the Delta. Machiskinic's family has filed a civil suit against the hotel company.

Post-inquiry gaps

The vast majority of recommendations from coroner's inquests get a response. Many are quite detailed. Several point out that agencies are already doing what's being asked of them or something similar.

Some have brought immediate results, such as more workshops on Indigenous social history for staff at Saskatoon's Regional Psychiatric Centre (RPC). Others have sparked promises, such as a pledge from Correctional Service Canada, which runs RPC, to aim for 20 per cent Indigenous employment by 2022.

Some garner no response for months or years. Others get responses that do not satisfy people who went through the inquest process.

In 2015, Shauna Wolf, 27, was found unresponsive in a single-bunk cell at Pine Grove Correctional Centre in Prince Albert.

In May 2017, an inquest jury heard Wolf was transferred from a medical cell to a segregation cell before her death because she smuggled in heroin. A nurse testified she believed Wolf died from opioid withdrawal.

The jury made more than a dozen recommendations to Saskatchewan's Ministry of Corrections.

"There were some very basic recommendations that came out of it, like 'Check on people who are sick,'" said Murray, who represented Wolf's family.

The ministry's response — received on Oct. 23 of this year, more than 16 months after the inquest — was not available from the coroners service website as of earlier this week. It was posted after CBC News asked about it.

Wolf was ultimately underwhelmed with its four brief paragraphs and their promise of a working group to "attend to the recommendations." She called the response tragic.

"There's no level of detail whatsoever about who's on this working group, which recommendations they are looking at, what's going to be implemented," said Murray. "You'd think in a year and a half some progress could be made."

"The families come in having lost somebody they love very much and want to see that people have learned from their tragedy, that things are going to change," she said.

A 2014 report that responded to a jury's call for more medical professionals at Prince Albert Youth Residence wasn't posted on the coroners service website until this week.

Another recommendation, stemming from an inquest into the death of Vincent Sewap, is still missing any response. The jury in that case called on Saskatoon's Royal University Hospital to install low-impact flooring to reduce the risk of head injuries from falls.

A spokesperson for the Saskatchewan Health Authority told CBC News this week that "officials have shared this concept with the design team and Infection Prevention and Control team to see what options are available."

Sewap died in August 2013.

Checking in on changes

Even when groups commit to carrying out juries' suggestions, the outcomes can remain unclear.

Adele Jennifer Morin was found unresponsive in her holding cell at the Sandy Bay, Sask., RCMP detachment in 2014. The inquest jury suggested in September 2016 that the RCMP replace the plexiglass windows on the detachment's cell doors to ensure members could see clearly through them.

The RCMP agreed two months later, saying it would replace the windows as soon as possible. But while the RCMP monitors its inquest responses internally, no further update was on file with the coroners service.

An RCMP spokesperson told CBC that the windows were replaced in June 2018.

Inquest as legal triage

Despite their shortcomings, coroner's inquests can be useful in paving the way for a potential civil lawsuit, Piche said.

"You have the same witnesses [at inquests] that likely would be present at the civil trial," he said. "They're subject to cross-examination. The disclosure that's provided by the coroner's office is often much the same as what would be at play in a civil trial."

Inquests can also have the opposite effect, said Murray.

"It can very clearly set out to a family, 'Hey look, there's no civil liability here on anybody. This was completely unpreventable.' That ends up saving the families money."

'Hope for the best'

Jordan Lafond's mother was disappointed with the jury's recommendations. Charmaine Dreaver said she wanted to see more, such as a recommendation that officers be barred from reviewing their dash-cam footage after an incident, as one officer admitted to doing during the Lafond inquest.

Despite her own experience, Dreaver is hopeful Dorothy Laboucane, Brydon Whitstone's mother, will get more out of the inquest process in Battleford next week.

"I'll be sending prayers and strength and everything," said Dreaver. "We've got to stand together and hope for the best."

A record of Saskatchewan coroner's inquest jury recommendations and responses can be found at this link.