The pressing need to learn from Indigenous elders

CBC Saskatchewan, Manitoba and the North examined how the role of elders is evolving in today's society

This series was originally released on Nov. 11, 2019.

Elders are storytellers, teachers, protectors, healers and pivotal members of Indigenous communities in Canada.

Many grew up speaking an Indigenous language, learning ceremony and living off the land. Several are also survivors of residential school or the Sixties Scoop.

As the current generation of elders ages — some particularly respected elders have died in recent years — some people worry about the knowledge lost and the voids left in their communities.

While the essentials of elders' roles haven't changed, the world they're living in today presents a new set of challenges.

Much of the younger Indigenous population across the country is growing up separate from their culture and language, often in urban settings. This disconnect, exacerbated by the intergenerational effects of colonization, has ignited an urgent movement to maintain Indigenous culture.

CBC Saskatchewan, CBC Manitoba and CBC North embarked on a months-long project to speak with elders, elders-in-training and youth from across their vast territories to learn how these knowledge keepers view their role today — and why they're more critical than ever before.

Margaret Leishman is an elder living in Kakisa, N.W.T. She describes in her own words what being an elder means to her.

In high demand

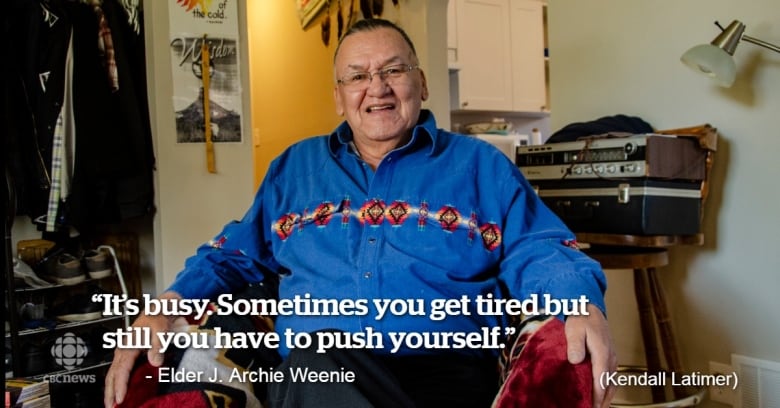

The role of the elder has expanded beyond Indigenous communities and what some would consider traditional. This emotional and physical work can be taxing. With that comes the risk of burnout.

Elder J. Archie Weenie, who lives in Regina, is approached for help daily. He doesn't say no.

Youth is the priority

A common thread across the conversations with elders was the importance of connecting with youth and how it is proving increasingly difficult.

One grandfather lamented how time with elders is being replaced by screen time.

You must have that drive within yourself — to replace screens with trees, headphones with drums.- Joachim Bonnetrouge, elder from Fort Providence, N.W.T.

For instance, a legacy of colonialism has left many young Inuit struggling to retain their culture. In Cambridge Bay, Nunavut, a group of grandmothers is fighting to change that at Annana's Camp.

In Cambridge Bay, as with everywhere, fewer and fewer kids are growing up learning Indigenous languages.

That's why a group of Cree elders on Nisichawayasihk Cree Nation in Manitoba is attempting to create a syllabic dictionary.

"They need to be educated in their language and their culture," said Elvis Thomas, from Nisichawayasihk. "Unfortunately for us, it's been dominated by the British and French versions, but we're beginning to make inroads, and the language and culture program is part of that."

In Pinehouse, Sask., two elders have used a lifetime of experience to positively influence youth in the northern community.

The pitfalls Elder Yvonne Maurice has encountered throughout her life, especially being bullied as a child, have motivated her to make sure any teen she meets won't fall down in the same ways she did.

Maurice has worked with children at a local school for more than two decades. More recently, she has run sharing circles at the high school, baring her own wounds, including the 2018 suicide of her youngest son.

Elder Annie Natomagan believes modern kids need the same thing to survive as she did — Through residential school in the 1950s, the births of her 13 children, the miscarriage of one and the death of two, as well as nearly 60 years of marriage, she turned to the old ways: speaking Cree and living off the land.

Thanks to the ripple effect of her survival knowledge, two young men in Pinehouse are dreaming of taking down a bull moose, rather than hitting the bottle.

Adults yearn for time with elders, too

An Ojibwe grandmother from Manitoba recalls ancestral teachings that were lost in residential school, which she then reclaimed thanks to time spent with her father and elders.

Next generation

Tala Tootoosis says she was told that she is "an elder-in-training."

She's 36.

The mother of four from both the Poundmaker Cree Nation and the Sturgeon Lake Cree Nation in Saskatchewan refers to herself on social media as a "kokum-in-training." (Kokum is the Cree word for grandmother.)

No matter how many mistakes I make, I still feel like I'm obligated to learn, because if I don't, I feel like nobody else will.- Andre Bear, 24

She's one of several younger people considered the next generation of elders. They are taking on the responsibility of learning traditions and ceremony, and taking on leadership roles in their communities as elders die or find themselves overloaded. This younger generation is also bringing their own take on what it means to be an elder.

With files from Kendall Latimer, Madeline Kotzer, Kate Kyle, Mark Hadlari, Donna Carreiro, Marilyn Robak, Ntawnis Piapot.