Extent of contamination from former Regina refinery site still unknown 45 years after shutdown

Critics question Sask. government's voluntary approach to regulatory oversight

Saskatchewan's Ministry of Environment admits it still doesn't know how much contamination was left behind by an Imperial Oil refinery in Regina that was shut down 45 years ago, or what effects it may be having on human health and the environment.

According to documents obtained by CBC, the ministry has known for decades that at least some of the site, which sits over two aquifers, was contaminated with petroleum hydrocarbons (PHC) and other toxic chemicals. Documents also reveal that construction companies building on the site were warned about the potential for explosions or workers collapsing because of the fumes.

Critics say the government is still in the dark about the state of this site today because it allowed Imperial to determine what environmental assessment needs to be done and let the company set its own timeline.

"It sounds very much like the whole file was just completely dropped at some point," said Chris Severson-Baker, the Alberta director of the Pembina Institute, an environmental think tank.

"No follow through, no willingness to enforce their own rules."

The refinery began operation in 1916. According to a Regina Leader-Post article from 1971, the facility was a rush job, built in just three and a half months to support the war effort.

Located just southwest of Ring Road in northeast Regina, it operated until 1975, when it was shut down and decommissioned. At its peak, the facility was capable of refining 22,500 barrels of oil per day.

Over the decades, there has been a range of studies and assessments on various parts of the approximately 80 acre parcel. Some have indicated PHC contamination to a depth of up to 10 meters. Others have uncovered elevated levels of benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, xylene, arsenic, thallium and lead in the soil.

These chemicals, some of which are cancer causing, can be harmful to human health if they're inhaled, ingested or touched.

Work in the area has also unearthed contaminated pipes and tanks that were left in the ground after decommissioning.

All of this raised alarms for Ministry of Environment officials over the years because the site sits on top of two aquifers, including the Regina aquifer, which serve as a backup water source for the city.

The fact that the ministry still doesn't know how extensive the contamination is has fuelled concern about potential impacts on a range of issues, from human health to the environment to property values.

Environmental condition is still unknown

The province acknowledges that historical contamination exists on the site.

Wes Kotyk, the current assistant deputy minister responsible for environmental protection, said in a 2009 letter obtained by CBC that the contamination happened decades ago, "when environmental legislation or standards did not exist or were much more liberal."

The province said in a recent email that when the site was decommissioned in the late 1970s, much of the above-ground infrastructure was removed by Imperial, but it's unclear what remediation of the soil was completed.

The ministry said that's because its files don't contain detailed records. The official noted that the province's environmental management act didn't come into force until 1984.

The ministry also said it doesn't appear the entire site has been assessed yet.

"We believe there are some gaps because ... we haven't been provided information to show that everything has been delineated yet," said Kotyk.

In a follow-up email, CBC asked what areas had not yet been studied.

"The south end of the property, north and north west off-site, westerly off-site, and east off-site may require additional site assessment activities in order to understand the contaminants of concerns, the extent of the contaminants and the potential risk to human health and the environment," the ministry responded.

Though 45 years have passed since the refinery was decommissioned, the ministry said it's still trying to work co-operatively with Imperial and the City of Regina, which owns a portion of the property.

"There have been no orders issued to Imperial Oil or the City of Regina," a ministry official wrote. "The ministry prefers voluntary action at impacted sites. This allows responsible persons to assess and apply corrective actions in a fashion that best suits their needs, yet still achieves the desired result of a reclaimed impacted site."

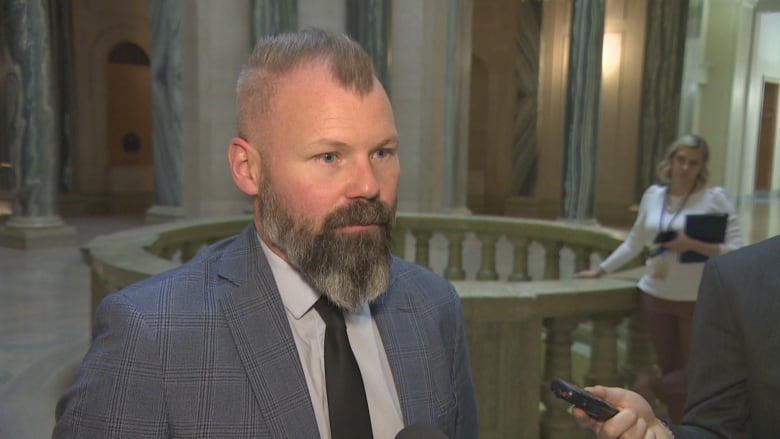

Saskatchewan's environmental protection legislation gives the Minister of Environment, Dustin Duncan, the power to order a land owner to conduct an environmental assessment and remediate the property if necessary.

Duncan told CBC he's satisfied with the ministry's oversight and he believes the assessment work has "been done to the level that the ministry feels is appropriate at this time, knowing that the file is certainly not concluded."

Experts question province's 'voluntary' approach

Severson-Baker said its "shocking" that the ministry still doesn't know the the extent of the contamination and the associated risk.

"I can't think of any examples, even some of the more egregious ones, where a company was allowed to decide whether or not to do that kind of work on its own," said Severson-Baker, noting he's been working in the field of environmental cleanup for 24 years.

He said in comparable situations in Alberta, the government has taken a much tougher line and required relatively quick assessment of environmental damage.

"Companies aren't going to voluntarily do anything that they don't have to do," he said. "So there has to be the risk that the government will impose something on them that they may really dislike."

Assistant deputy minister Kotyk said this is a complicated situation.

"With a site this complex, you can't do it all like in just one site assessment," he said. "Our seasons are limited to the amount of work that can be done."

He added that industry has limited resources and the ministry can't "impose horrendous costs for something that may not provide additional information."

Kotyk said that doesn't mean Imperial is off the hook. It just means the province takes a "risk-based approach," focusing on areas which pose the greatest potential threat.

Shaun Fluker, who teaches environmental law at the University of Calgary, said that without a comprehensive assessment a truly risk-based approach is not possible.

"You can't even be doing that if you haven't taken steps to identify and clarify exactly what the extent of the contamination is," said Fluker.

He said Saskatchewan's voluntary approach was common among Canadian provinces back in the 1970s and 1980s, but that this approach has now all but disappeared.

Fluker said governments are now "far more willing to go down the enforcement route and/or compliance with a heavy stick if needed to clean or get these sorts of areas cleaned up."

According to the ministry, Imperial and the city committed in 2009 to fully assessing the former refinery lands, but the ministry still doesn't have evidence that has happened.

The ministry told CBC it would be reaching out to both organizations to ask about the timeline and what they intend to do next.

Fluker said this passive style of oversight is baffling

"It seems like the department officials are well aware of this problem but are just sitting on it," he said. "It certainly raises questions as to what exactly the cause of the inaction or delay is here. That's a real puzzle to me."

Imperial Oil and the City of Regina have both declined comment on this story because the matter is before the courts.

Land owners launch class-action lawsuit

In 2010, a group of property owners led by Clint Kimery filed a class-action lawsuit against Imperial and the city.

The suit alleges both parties were aware of contamination on the site, but failed to notify the land owners "and actively worked to conceal information about the presence of contaminants in the class area in order to preserve their financial, political and economic interests."

None of the claims in the lawsuit have been tested in court. Neither the city or Imperial Oil has filed a statement of defence. The plaintiffs say the lawsuit has been inactive for years because they've run into roadblocks and run out of money.

Kimery's company, Gunner Mudjacking, is located on the southern portion of the former refinery site, which the province admits has not yet been assessed.

Kimery, the lead plantiff, said he filed the lawsuit because the uncertainty about contamination was affecting his business's property value and no one was willing to pay for the assessment.

He said that when he bought the land in 1988 he had no idea it was on the site of a former refinery with potential contamination problems.

According to Kimery, he learned about the issues during a tax assessment battle with the city in the early 2000s. At that time, he said, the city was attempting to triple his property taxes by deeming the land to be in a commercial area.

The more he learned, the more he wondered, "why would the city be assessing our property so high when we had that kind of history?"

He attempted to get a valuation of his land, but an appraiser told him in a letter, "there is enough evidence to suggest that further environmental investigation is required," and that until that happens, "we wish to advise that we cannot complete an appraisal."

Kimery said that puts him and the other property owners in limbo.

A documented history of contamination

He has provided CBC with a wide range of documents he obtained through access to information requests during his research.

Those documents show the City of Regina has been aware that parts of the site were contaminated since at least 1980 and the ministry has been aware since at least 1986.

Over the years, the city has approved the construction of a dairy creamery and a transit centre on the site, and also approved a wide range of businesses on the property, from a daycare to a food bank to an adult education centre.

WATCH: An aerial view of what the site looks like today

Kimery said it's infuriating that the city will approve all sorts of business activities on what it knows to be contaminated land and yet won't ensure the entire area has been properly assessed.

In 2008, after demands from Kimery and other property owners, the province asked Imperial and the City of Regina to conduct a Phase I assessment of the land, which would provide a high-level evaluation of the history of the site and the potential of contamination.

Based on the results, the province asked in late 2008 for a Phase II assessment, which is a detailed investigation involving drilling, soil and water testing and analysis.

By late 2012, the ministry had not yet received that report and was losing patience. This prompted an official to impose a deadline and threaten to take action if the report wasn't forthcoming.

The report, which was delivered in February 2013, said that most of the soil samples didn't exceed the existing guidelines for contaminants.

However it did find elevated levels of benzene, arsenic, thallium, lead and PHC at some sample locations.

CBC asked the ministry if it ordered or recommended any work be done as a result of this study. The ministry said it made no orders, noting that it prefers a voluntary approach.

An incomplete report

Kimery voiced several concerns with this assessment.

First, he pointed out, the test holes were just one foot deep.

He said that was an odd decision, given that as early as 1980 studies in the area had found "considerable contamination from hydrocarbons" to a depth of seven to 10 meters in "all test holes drilled on the site."

He said to make matters worse, the study likely was examining fill that the city had trucked in to level the property and not the original contaminated soil.

"There's probably three or four feet of fill over that entire area," he said.

When asked, the province said Imperial and the city have the right to decide how deep to test, noting "the person responsible for each impacted site has the option to use the endpoint that they consider most appropriate for the site, as long as compliance with the regulatory requirements is maintained."

Kimery is also concerned that this assessment only examined land owned by the city and not privately owned land. That meant large swaths of the site were not assessed.

Government emails show that the ministry wanted the entire site, including Kimery's property, to be assessed.

The ministry told CBC that in 2009, Imperial and the City of Regina agreed with the ministry's request to study the entire site.

But 11 years later the ministry is still waiting for that study and doesn't know when it will happen. In an email, the ministry said it "has not yet received a timeline on completion of future investigations."

Kimery said he believes the delay may be related to his ongoing fight with the city about taxes.

"The city, I think, did not want to give us any evidence of contamination. So that's why they stopped short of this particular area," he said.

When pressed on the 11-year delay, assistant deputy minister Kotyk told CBC, "we will be asking [Imperial and the city] to look at other areas."

Former Calgary refinery also faced contamination controversy

This isn't the only Imperial Oil refinery site that has been the subject of lingering questions about contamination.

In 1975, when Imperial shut down the refinery in Regina, it also shut one down in Calgary.

In 2001, it came to light that the site — which had been turned into a residential neighbourhood called Lynnview Ridge — was contaminated with high levels of hydrocarbons and lead.

After pressure from residents, the provincial government ordered Imperial to clean up the site. The company bought up and demolished 140 homes and several apartment blocks.

By 2018, the site had been cleaned up and reopened as a park.

The situation in Regina is quite different, given that there are no homes on the property and no evidence the contamination is as severe. But Kimery said it's surprising the government hasn't taken the assessment work more seriously, given the similarities.

"The Regina refinery is a third larger than the Calgary one and 10 years older," Kimery said. "So proportionally, you would think that the Regina refinery would be that much more contaminated than the one in Calgary."

Construction on contamination

In 1979, after the refinery was shut down, the City of Regina purchased a large portion of the property and then flipped some of that land to Dairy Producers Cooperative Ltd.

The city authorized the company to build a multi-million dollar creamery on the site, where for 20 years it manufactured food-grade dairy products.

Kimery's lawsuit alleges that during construction of the creamery, "there were reports of explosions due to flammable liquids and gases emanating from the refinery property."

Correspondence obtained by CBC shows Dairy Producers management was concerned about the site.

In a 1995 letter to the province, an official with Dairy Producers wrote, "we believe that there exists the possibility that the site is contaminated. The official said the company was worried this information could jeopardize a proposed merger.

The company asked the province for a definitive statement absolving Dairy Producers and its merging partner "of liability, if any, which may be associated with the contaminated site."

The ministry wrote back that while it couldn't provide such a statement, it could offer a "letter of comfort." The official noted the site was not listed on the province's "Action on Contaminated Sites" list, which identified locations that were under action, require future action or further study.

The province also assured Dairy Producers that the thrust of the provincial legislation is that the polluter pays for any clean-up. The province noted a clean-up order would only be issued as a "last resort."

The merger went ahead.

Dairy Producers shut down its creamery in the early 2000s.

Creamery gifted to Regina Food Bank

In December 2004, the company that owned the Dairy Producers property gifted it to the Regina Food Bank for the nominal fee of $200.

Kimery's lawsuit alleges that over the years, the City of Regina permitted and licensed the food bank "to set up food storage and distribution operations along with a technical institute, adult training school, computer centre and a child daycare and outdoor playground."

"This was all approved despite the fact that the environmental condition of the lands on which these operations would be located was unknown," the lawsuit says.

In a 2012 letter to the city about the food bank, the province confirmed that there was significant reason for concern.

"The Ministry of Environment has reviewed its files and recommends that no further development take place on the site," says the letter dated July 18, 2012. "The ministry recommends that the city of Regina deny future applications for further development on the site pending the completion of environmental and assessment activities as deemed acceptable by the ministry."

When the city sold the refinery land to the creamery, it also gave the company the right to sell property it didn't use for its facility. Dairy Producers developed Adams Street and sold lots to private businesses.

Kimery's business is on Adams Street.

After Dairy Producers shut down its facility, it sold four remaining lots totalling more than three acres to a car dealership, for $5,000. In a letter, the owner of the dealership said "the value of the lots were decreased due to environmental concern in respect of the property."

Kimery said that sale and the Dairy Producers transfer of land to the food bank prove the contamination is dramatically affecting property value. He said it's crucial that the province order a comprehensive study.

"We're kind of in a sea of contamination here," he said.

City built transit centre on contaminated land

In 1986, just as the City of Regina was preparing to build a facility for its transit fleet on the former Imperial lands, it received studies warning about contamination in the soil and groundwater.

One study noted that while above-ground structures had been removed, there were underground storage tanks and an extensive system of industrial piping that remained at least partially intact. The report also said there was evidence of "considerable contamination" from hydrocarbons as deep as 10 meters underground and that the "hydrocarbon contamination is considered potentially severe."

It warned of possible consequences for construction workers if the city decided to build its transit centre on this site.

"There is potential for explosions should gas collect in confined areas," the report warned, adding that the strong hydrocarbon odour raises the "possibility of workmen collapsing due to the fumes."

A second study warned that because the property sits on top of the Regina aquifer, "there is a potential of hydrocarbon contamination migrating deeper into the 'A' Zone of the Regina aquifer." It said part of the Regina aquifer "shows evidence of contamination."

The study found that "at the Imperial Oil site there are possibly three separate leachate plumes evident." A leachate plume is a migrating solution of harmful chemicals.

The study said the plumes appeared to be moving underground and "extend an undetermined distance beyond the boundaries of the aquifers investigated." It noted that the Regina aquifer discharges into the Wascana and Boggy Creeks.

The study recommended additional investigation.

No evidence of aquifer contamination: industry study

The city provided these studies to the Ministry of Environment in June 1986, just as construction on the transit facility was set to begin. That raised concern for the ministry, which asked for additional study.

A follow-up study was conducted by Esso, a division of Imperial, and the ministry said that document cast doubt on the earlier study.

In a 1989 letter to the city of Regina, an Esso official summarized the findings.

"The study determined that the refinery 'has had little or no effect on either aquifers'" the official wrote. "There are no refinery induced plumes ... from the site as initially indicated [ by the earlier study]."

The ministry said ground water is regularly monitored and it's satisfied that all the appropriate controls are in place to protect human health and the environment.

Despite the pipes and contamination in the ground and the concerns raised by the studies, documents show the transit centre construction project moved forward rapidly.

According to meeting minutes in the summer of 1986, "the construction plan is to build over what is on the site as much as possible," and "serious contaminated soil was to be spread at the north end of the site." While some contamination was removed, a city memo said "total removal of contaminated soil... is not considered practical."

Controversy between city and ministry

Documents show that the city and the ministry were arguing around this time about who should be taking the lead in assessing and remediating the property.

In a July 1986 letter to the ministry, a Regina official said the city believed that further investigation was required and that work "must consider the entire former refinery and associated areas," because despite all the unknowns, "there appears potential to find a considerable problem."

The official wrote that the city is just one of many property owners on the site and for that reason the province needs to play an active role.

"The city is of the opinion that the senior government and the city should be spearheading future investigations and mitigation action at the Imperial Oil site," he wrote.

An internal City of Regina memo from around that time reported that the province believed this was the city's problem.

"Saskatchewan environment disagrees and expect the city to develop an appropriate program of further investigation on our own property and if we think an expanded program is necessary, to pursue this also on our own," the memo says.

The Ministry of Environment's position doesn't appear to have changed in the 35 years since.

In a recent email, CBC asked the ministry why it was pushing this responsibility on to the city.

The ministry replied that it expected the city and Imperial "to continue to jointly manage and co-operate on future activities at the site."

The ministry appears to have regularly taken this position over the years.

Province says city is responsible

In 2003, an assessment of property that had been owned by Dairy Producers found the land was contaminated in excess of Canadian standards for commercial/industrial land use. Despite that, the report says, "no potentially impacted soil was removed from the site."

The next year, that land was transferred to the Regina food bank.

CBC asked the ministry whether anything was ever done about this contamination and why a food bank and a daycare were allowed operate on this site.

The ministry replied that when contamination exceeds existing standards then additional investigation "is warranted." However, the ministry said it doesn't know if any additional assessment or remediation work was done. A ministry email said it's the city's responsibility to approve land use and development in its jurisdiction.

More recently, in 2016, the city commissioned studies of the area around its transit centre, as it was considering expanding the facility.

One study found elevated levels of benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, xylene and PHC in the ground, and benzene and toluene in the water.

Another study concluded "the extent of PHCs under the transit building was uncertain and as a result vapour barrier and PPE were recommended for construction workers and workers were told not to dig too deep."

The ministry once again told CBC that when standards are exceeded, "additional investigation is warranted." However the province has no idea if that work was ever done.

"There has been no additional site assessment work submitted to the ministry since the 2016 report," the ministry said, once again stating that the city is responsible for all development decisions on its land.

Kimery said he's been at this fight for more than a dozen years and feels he's run out of options.

His lawsuit has stalled. Officials and politicians at the city have become inaccessible.

"I keep getting intercepted by the city solicitor's office telling me that any communications that I do with [politicians or bureaucrats], has to go through their [legal] office," Kimery said.

He hopes that the political pressure that can come from publicity might push politicians to do the right thing and ordering a comprehensive review, even if it comes 45 years too late.