Pan Am comedown: Why some athletes have trouble leaving the sports world

Life coach says the key is understanding that you are more than just an elite athlete

The flame will soon be extinguished, the stands emptied and the roar of the crowd silenced.

Toronto's 2015 Pan Am Games are drawing to a close.

For most Canadian athletes, there's little time to become nostalgic about the thrill of competing in front of a hometown crowd. We're coming up on an Olympic year, after all, and that means jumping right back into more training, more qualifying events and more travel.

- Damian Warner breaks Canadian, Pan Am decathlon records

- What's On: Pam Am Games Closing Ceremony and more

- Petition against Pan Am Games gig passes 30 K backers

It's a disciplined, structured and sometimes insular life — until it's not.

For those athletes who are moving on from elite competition, the transition to a life without strict schedules and regular accolades can be a rough ride.

"I was always introduced as, 'This is my buddy who went to the Olympics,' not like, 'This is Gavin, my friend.'

"But when it stops happening, you think, 'But wait a minute, I used to be somebody, right?"

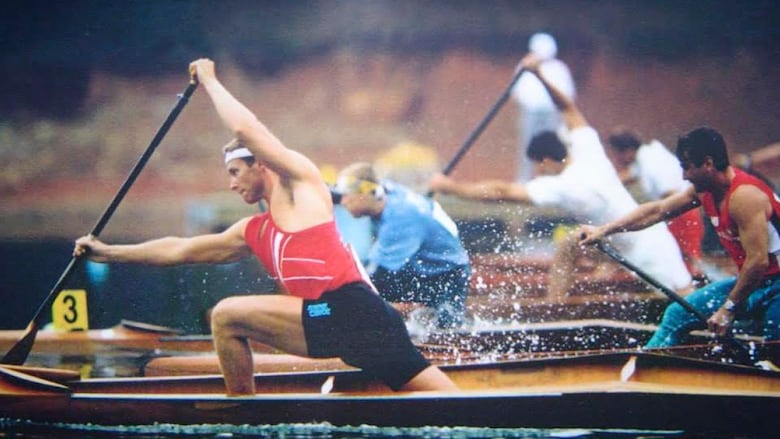

Now a chiropractor in Mississauga, Ont., Gavin Maxwell was a member of Canada's national paddling team for 12 years. He competed in the 1996 Olympic summer games in Atlanta, seven world championships and the 1991 Pan Am Games in Cuba, where he won two bronze medals.

When he stepped away from competition in 1999, it was a much bigger blow than he'd ever anticipated.

"I've always visualized Wile E. Coyote and the Road Runner, where he'd be racing after the guy and then there's the cliff. And that was how I felt — that my life was paved up to this point, and when I finished sport there was no pavement."

Identity crisis

Competitive athletes often take up their chosen sport from a young age, and depending on the discipline, some of them can continue competing into adulthood.

So it's not uncommon for an athlete to feel a bit lost, untethered or even depressed when they come to the end of their sports career, says University of Toronto sports psychologist Gretchen Kerr.

"They've identified themselves as athletes for so long, and they've had to focus almost entirely on that identity. So when they don't have that, it's, 'Who am I, what am I all about and where am I going next?'"

It's been nearly 16 years since Gavin Maxwell retired, but he says he still misses competitive sport every day.

"It was a passion of mine, I never once woke up and thought,' Oh damn I've got to go paddling,' so once it was over it was really tough. It was just this massive loss."

Maxwell thinks there should be more of a support network out there for competitive athletes who don't have time to think of the future.

Executive life coach Lindsay Sukornyk says that one of the aims of her business, North Star Coaching and Yoga, is to help elite performers, such as athletes, make healthy transitions from their competitive careers to the next phase of their lives.

She says that in order to achieve that, however, the individual needs to see that being an elite athlete is only a fraction of who they are as a human being.

"The 'athletic champion' lens may be quite large and very shiny, so they may have to work a little harder to shift their view to see all the other roles that they can play," says Sukornyk.

Still in the game

Canadian Pan Am competitor Samuel Schachter is nowhere near retirement, but he's thought about his post-athletic future.

The 25-year-old and his beach volleyball partner, Josh Binstock, finished out of medal contention at this year's Pan Am games, but they've quickly dusted off the sand. They don't have a choice.

In their push to qualify for the Olympic team, the Richmond Hill, Ont. duo have two more grand slams and other important events to compete in starting in less than a month.

While he says his post-volleyball life is a little scary to think about, Schachter admits he has a "little bit of a plan."

But he stresses that when you're a competitive athlete, you've got to "burn the boats," to quote one of the team's technical directors.

"You can't look at other things as your backup plan," says Schachter. "Once you commit to [a sport], you've got to fully commit."

Forever the competitor, Gavin Maxwell agrees that athletes can't get distracted from their training. But he urges them to have a bit of road map.

"I had to reinvent myself, like, 'How am I going to make a living and how am I going to find contentment and fulfillment in my life?' And it's taken me a long time to do that. I'm still searching for it."