How social media apps modelled after Tinder are revolutionizing sperm donation

Doctor, legal expert say people should be careful if they forego more expensive regulated clinics

Swipe right if you like him, swipe left if you don't.

It's a phrase that's no longer just for dating apps like Tinder. It's how a growing number of families are now seeking out sperm donors — and how sperm donors are getting a chance to choose who gets their DNA.

CBC and Radio-Canada spent a month reaching out to men and women using apps similar to Tinder to help with the match-making.

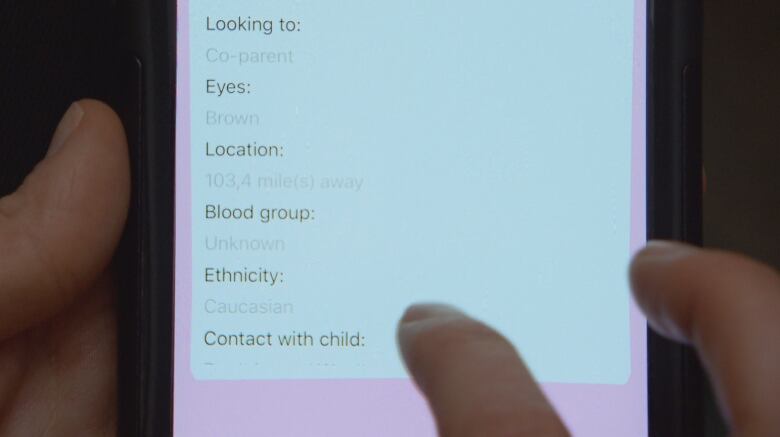

For a month, we created an account and used one of these mobile applications, Co-ParentMatch.

Using photos, we could sort through potential donors and they could also select us.

None of the men asked for compensation for their donation, but they wanted to make sure their DNA ended up in good hands.

Sperm banks? Not for them

Most of the men who agreed to speak with us said they had decided against using a more formal sperm bank, finding the experience cold and too clinical.

Moreover, they wanted the right to have a say in who would be the mother of their offspring.

Michael Meyer, a 33-year-old man from New York and one of the few donors who agreed to let us use his name, said he did not see himself in a traditional family.

But he still wants to leave a mark after his death.

"I try to find people who if we had met under different circumstances … maybe we would have hit it off," explained Meyer.

A 29-year-old donor from San Diego who preferred not to reveal his identity said he became a donor because he fears his health will deteriorate before he has time to begin his own family.

He's been diagnosed with a degenerative disease that can be transmitted to his children only if both parents carry a specific gene.

He too said he values the ability to have a say over who carries his DNA, an option sperm banks don't offer.

"I realized that in the clinics, they don't tell you where your donation went," he explained.

"It's a really cold and disconnected process. And for me, giving my sperm is a very personal thing."

A 40-year-old man who calls Ottawa and Toronto home said he's too busy with his healthcare career to be a dad.

Still, he said he wanted to be a donor because he felt it would be a shame if his DNA would not be passed on to the next generation.

Families want more choice

While donors are looking for a chance to be involved in the matching process, families said they're able to take advantage of the low cost and greater selection available using these apps.

Julie Déziel and her same-sex partner used the same sperm donor from the internet for all three of their children, including their most recent infant, Laurence.

One of the big incentives, according to Déziel, was the ability to meet the donor and do the process right in their own home.

"When you do it, it becomes a kind of bond," explained Déziel.

She said she now jokes that because she was the one to inseminate her partner at home, she can say she impregnated her partner.

Cost was another incentive, since each sperm donation purchased at the clinic can cost $1,000 — with no guarantee that it will end in a pregnancy.

"I didn't have the means," said Déziel. "I think a lot of people are choosing home insemination for this very reason."

The risks of home insemination

While social media is having a disruptive impact on traditional sperm banks, fertility doctors who use them say there are benefits — but those searching for donors online should understand the risks.

Dr. Arthur Leader with the Ottawa Fertility Clinic pointed out that there are a number of procedures undertaken with sperm donors aimed at protecting both mother and child.

He warned there could be some danger in finding donors through social media.

"There's no information on the genetic or the infectious status of the donor, and there's no consideration for the health and safety of the woman who's using the sperm, or for the health and safety for the children born," he said.

At the clinic, donor sperm is frozen for a period of six months to detect infections or diseases such as HIV or hepatitis B, Leader said.

In addition, an analysis of the DNA profile of the mother and sperm donor is done to detect any abnormality or incompatibility.

But not all spermatozoa resist the cold. Only 10 out of 1,000 sperm donations contain sperm strong enough to survive freezing, Leader said.

"This means that most are rejected for psychological, medical, genetic or infections problems," he said.

Nor is there any guarantee, said Leader, that the children will ever get access to information about the donor.

Legal obligations and rights of donors

Traditional sperm banks include applications and contracts that waive the normal parental rights and obligations of a donor to the children.

Some donors obtained through social media sites have also started signing contracts waiving their parental rights. However, parental law expert Doreen Brown warned that these contracts have not yet been tested in court.

She suggests sperm donated by actually having sex could make things more complicated for those involved, but even without sex, families have faced legal challenges.

"I've had a case in the past where it was two women and the sperm donor was a friend," said Brown.

"They hadn't signed a contract. They hadn't had any sexual relationship. [But] in the end he sued the two women and the court agreed with his application, and his name today is on the birth certificate. "

Changes to federal law

On Sept. 30, 2016, the federal government announced that Health Canada intended to update the Assisted Human Reproduction Act. The review would allow Canadians to have better access to "donor reproductive tissues," while reducing the risk to users of assisted reproductive technologies.

One of the changes would make it less expensive for families to use donors of their choice rather than anonymous sperm bank donors, allowing them access to the rigourous testing available at the clinics.

Céline Brown of the Association of Infertile Couples of Quebec applauds this move.

"We say that we should really put in place some rules so that the opening is there for families to have more control over donor semen," she said.

"Certainly by finding someone on the internet we do not know if he has a medical history, if there are DNA problems, or serious genetic problems."