The staggering number of children reported missing from Nova Scotia group homes

Father whose daughter ran away from group home says she was turned into 'hardened street child'

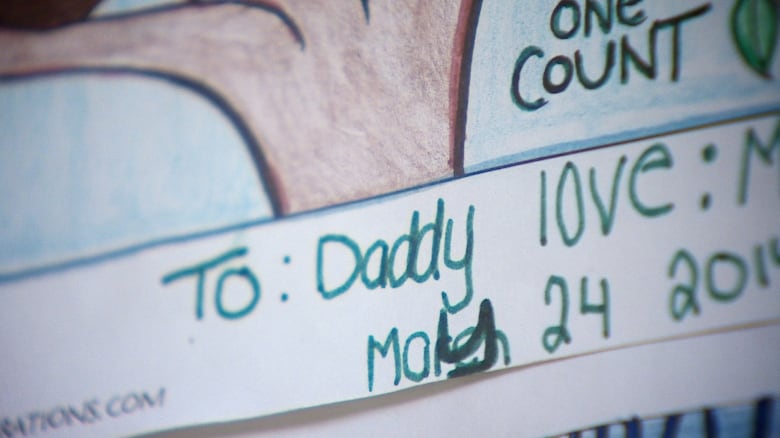

The moment Greg regained custody of his 16-year-old daughter last summer, he immediately asked a social worker: "Where is she?"

That's when he learned she was missing — again — from the Nova Scotia group home where she'd been living. No one had seen her for weeks.

"My heart just dropped," says Greg, whose real name is not being published to protect his daughter's identity. "It's like winning a million bucks and you put it in your hand and the wind just blew it away."

After voluntarily signing his daughter into provincial care in 2013, convinced it would lead to better treatment for her severe mental-health problems, Greg had finally won the legal battle to get her back.

But it would be months before the teen finally slipped out of the shadows where she had been hiding in Halifax. She had become addicted to crack and run into the arms of a pimp who sold her for sex. Tired and hungry, she eventually reached out to her family.

Her struggle is disturbingly common among youth in provincial care.

Data provided to CBC News under freedom of information laws shows between January 2011 and December 2016 there were 2,655 reports of children missing from Nova Scotia's 15 group homes, which are residential facilities for youth up to 18 years of age in provincial care whose emotional or behavioural problems are too severe for foster homes.

That's an average of about one a day, and even then the data for one year doesn't appear complete.

Protocol requires staff at provincial group homes to ring police 15 minutes after curfew is broken, and in every case police and social workers were called. But while many youth return to their care facility within hours, others stay away for days or even weeks.

The numbers alarm Paul Sheppard, a youth criminal lawyer with Nova Scotia Legal Aid whose work mostly involves children from group homes. He said the number of missing youth is staggering.

"It's a very high number and I think it should cause a lot of people concern," he said. "I certainly can't say that I've had a young person express to me that they particularly enjoy residing in these homes, so I think the short answer is that there's probably a lot of different explanations for that number."

He said in many cases, especially with girls, pimps have coerced or forced them into prostitution. Many of the girls who come through his legal aid office have either been approached or taken advantage of, he said, or know someone close to them who has.

"That may explain some of the cases of these young people that are going missing for periods of time," he said.

The data provided to CBC News does not reveal gender, length of time or repeat incidents. In several cases, multiple missing children are documented as a single report.

The numbers for 2015 appear to be incomplete for all group homes, with months during which no incidents are reported. The Department of Community Services admits there may be cases where incidents were not properly logged and there's work to be done to improve that.

Wendy Bungay, director of placement services for the department, said children who run away for longer than a few days are "really exceptional cases."

"If [staff] have any belief at all that there may be any kind of risk, they're going to make that report. But we do know that a lot of time the duration of the absence is very, very small," she said.

Social workers make every effort to stay in contact with missing youth through social media or text messages, Bungay said, and there's a good relationship with police.

"If we have children we know are higher risk, it's being able to make sure there's a community response looking for them, reaching out to them, letting them know that people care," she said.

Greg, the father of the teen who spent three years in provincial care, believes living in different group homes turned his daughter into a "hardened street child."

"Like people that come out of jail — hardened. Feelings lost, street savvy, knows how to slick away to the cracks and hide from people and police," he said.

He said he was encouraged by health professionals to give up his parental rights so his daughter could be treated at Wood Street Centre, a secure facility in Truro, N.S., for children in provincial care. She had been cutting herself and running away from home by the time she was 12.

"It started at IWK [Health Centre], who gave me information of how to do it and then it was me making the phone call to the agency, and then going in the next day bawling my head off, not wanting to sign a piece of paper," Greg said.

"But it was the only way I could get my daughter help, where they could stabilize her."

He said he was led to believe it would only be for six months. Before that period ended, the province sought a protection order to put her into temporary care.

Greg now says signing that piece of paper was a "grave mistake." He admits his daughter was a severe case, but argues the province made things worse by bouncing her between group homes and institutions.

She went to Wood Street several times. The girl also stayed in three other Nova Scotia group homes, and spent one year at a youth residential treatment centre in Saskatchewan.