Before Maud Lewis was famous, this artist saw something special in her work

Willard Ferguson's silkscreen prints are resurfacing 60 years later

A Nova Scotia art collector has discovered hundreds of forgotten Maud Lewis silkscreen prints and is sharing the little known story of the man behind them.

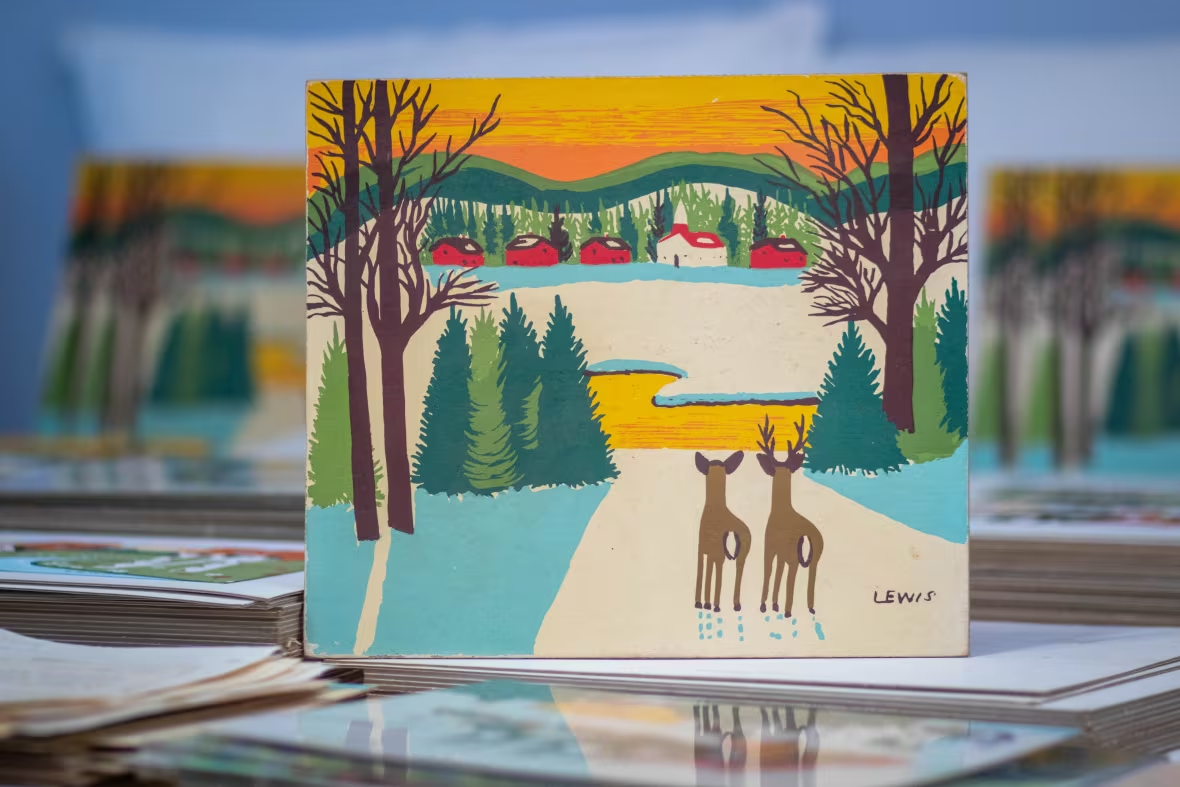

The vintage prints, some of which were made by hand when Lewis was still alive, aren't original paintings, but rather depict the beloved artist's now iconic images — from the oxen in front of rows of tulips to the three black cats.

Willard Ferguson, an artist and gallery owner, worked out an agreement with Lewis to reproduce nine of her images beginning in the early 1960s. He died more than a decade ago, and his contribution to promoting Lewis's work before she was famous has become a mere footnote.

Chad Brown wants to change that.

"When it comes to silkscreens, it's as close to an original as you're going to get and I think that that's what he wanted," said the entrepreneur from the Halifax area.

Brown, who bought his first silkscreen print on eBay a few years ago, discovered more than 200 prints at a Ferguson family estate in October. He bought everything that he could fit in his car.

Long before a single Lewis painting could earn $45,000 at auction, Ferguson was among a small group of Nova Scotia artists and art lovers who saw genius in her simple lines and bold colours.

Ferguson co-owned the Ten Mile House gallery in Bedford with Claire Stenning, where they also sold Lewis's original framed paintings. The duo was interviewed in a 1965 documentary that aired on CBC about Maud and Everett, singing the artist's praises and wondering why more people weren't.

"He wasn't recognized much for his part in it," said Ferguson's son, Bill Ferguson. "Other people have claimed more fame than my father and Claire Stenning and Cora Greenaway, who were the ones that were really pushing her."

He said his dad was always drawn to Lewis's work.

"It's very primitive, but the colour, the life from this lady who suffered a lot, and she just brightened up so much when you look at those," he said.

He remembers driving with his dad to Lewis's highway-side house in Marshalltown when he was about 12 years old.

"It was a tiny, tiny thing, cluttered, just full of stuff, and Maud was just a tiny person and crippled up quite badly," he said. "And my dad had seen her art and just was taken by it and he felt she could really do something for Nova Scotia."

Bill Ferguson said his dad signed two copyright agreements with Lewis, but he only ever saw the one that granted his dad permission to reproduce her art on postcards.

He said the other agreement, which he remembers being written by a lawyer in Truro, gave his dad the copyright to use Lewis's images on the silkscreens.

Part of that agreement stipulated that Ferguson and Ten Mile House couldn't sell their silkscreens in Lewis's county of Digby, Bill Ferguson said.

But there was a problem with this business venture.

Lewis was still selling her original paintings for around $5 in the early 1960s. It cost more than that to have the prints made by a local silkscreen artist and each one of them was priced around $15-$25.

"He wanted to promote her, help her, but also I'm sure he was in business for himself to also make money, and this is where he needed her to raise the price for her real paintings," Bill Ferguson said. "It's hard to sell prints that cost you quite a bit of money when the pictures, the real pictures that she made herself were selling very, very cheap."

Even after Lewis died at the age of 67 in 1970, her original paintings were selling for a remarkably low price. Brown said the silkscreens never made much money for Ferguson — or for Lewis, who doesn't appear to have received any royalties from the prints.

"I think he was just doing it to get by," said Brown. "I honestly don't think he had the extra money to provide her, and if he did, I think he would have."

It's unclear how many of the vintage prints exist today. They were handmade using a tedious process that required the artist to stencil one colour, wait for it to dry and then do the next colour, said Brown. The later ones were made by machine.

Maud Lewis expert, Alan Deacon, who bought his first Lewis painting from the artist herself for $10, has never figured out why it took so long for her appeal to catch on.

He gives talks about the life of Lewis and said Ferguson and Stenning's silkscreen project may have been modelled after Lewis herself who did serial images, meaning she painted the same picture over and over again.

"They were doing sort of a similar thing that she was able to do and maybe they could do them a little bit quicker … and this would be a bit of a legacy as well on her life," Deacon said. "They must have known that, you know, she's pretty frail. She doesn't look that well."

Now, 60 years later, Ferguson's prints are resurfacing and some of the older ones are being sold for more than a thousand dollars.

The Winding River Gallery in Stewiacke received about 20 silkscreens a few years ago and is selling them for $1,200 to $1,300.

Brown is selling his prints for between $350 and $2,000, depending on when they were made, and said he's had a lot of interest. He plans to sell some of them but keep the majority of the collection for himself, he added.

"It was the intention that everybody owned and was able to afford a Maud Lewis so these are as close as a second best as you're going to get," he said.

Still, there are mixed views about where exactly the prints fit in the story of Maud Lewis, who has taken on cult status not only in her home province but around the world.

Deacon said he's known of people using the silkscreen prints as fakes, adding paint onto the image to make it look like Lewis's brushstrokes.

A spokesperson for the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia declined to comment on Brown's collection, saying the gallery is not interested in reproductions, only originals.

The gallery now has the copyright to reproduce Lewis's work. Its copyright holding was set to expire in 2021, 50 years after her death, but a proposed change to NAFTA that would bring Canada's copyright laws in line with the U.S. could extend that.

Bill Ferguson is glad people like Brown are taking an interest in what his father did, and that the rest of the province, and the country, has finally caught up with his love of Lewis.

"He would think it's fantastic because he was trying to push it and get it out there, but certain people just didn't appreciate it, and that movie really gave it a second resurgence there and it really took off," he said.

Ferguson, an artist in his own right, was born in England and moved to Montreal with his family as a young boy. But it was his adopted home of Nova Scotia that always fascinated him, said his son.

Bill Ferguson remembers driving around with his dad on Sundays to visit artists in every corner of the province. Sometimes the pair would stop at a river so the younger Ferguson could fish while the older one painted what was around him.

Willard Ferguson, like Lewis, saw beauty in the rugged coastlines and farms that dot Nova Scotia.

"Some people look at a painting [and say] that's made by so-and-so, that's worth so many million dollars. But do you really like it? Do you enjoy it? What do you see in it? That to me is what's more important."