Use of facial recognition technology by police growing in Canada, as privacy laws lag

'They're intrusive technologies that need to be regulated,' Halifax lawyer says

Canadian privacy advocates are calling on all levels of government to create specific regulations around police use of facial recognition technology.

Canada doesn't have a policy on the collection of biometrics, which are physical and behavioural characteristics that can be used to identify people digitally. Because of that, there are no minimum standards for privacy, mitigation of risk or public transparency, according to the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada's website.

In that vacuum, some police departments in Canada have begun to use facial recognition technology.

Calgary police regularly use it, and Toronto police have tested out their own system. Edmonton and Saskatoon are considering it. Montreal police would not confirm whether they use facial recognition systems. Halifax, Winnipeg and Vancouver say they do not. Other police forces contacted did not respond to inquiries.

The RCMP say they are not using facial recognition technology. "However we continue to monitor new and evolving technology," the force said in an email.

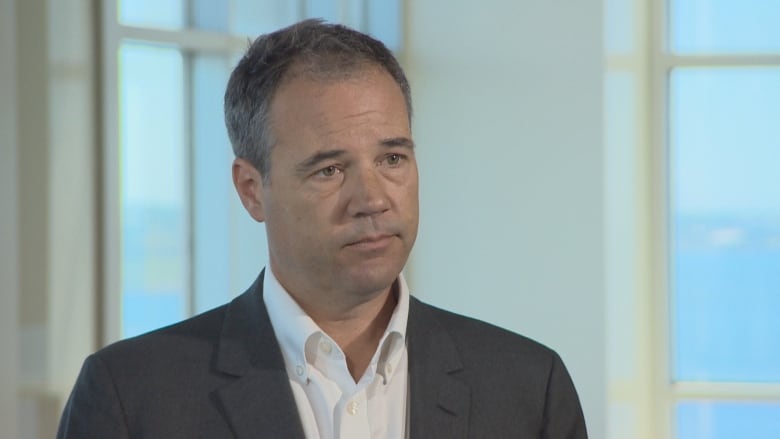

"I think legislators and policy-makers need to turn their minds to this," said David Fraser, a privacy lawyer with McInnes Cooper in Halifax.

"We need to have this discussion, and the police need to be dragged into that discussion, out of the shadows where they're making decisions about currently deploying this sort of technology."

Biometrics enable a device to recognize an individual. Facial recognition is a type of biometric system.

Those systems work by scanning an image of a person's face to identify unique measurable characteristics, like the distance between someone's eyes or the width of their nose.

A computer creates a representation of the face and then compares it to the images in a database in an attempt to find a match.

Fraser and others worry widespread use of this technology without proper oversight could erode individual privacy.

"Broadly speaking, our office has identified facial recognition as having the potential to be the most highly invasive of the current popular biometric identifying technologies," Vito Pilieci, a spokesperson for the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada, said in an email.

Last fall, privacy advocates and commissioners from across Canada urged federal, provincial and territorial governments to modernize privacy laws to better keep pace with technological change.

But Nova Scotia's Office of the Information and Privacy Commissioner said it isn't aware of any province with legislation to specifically address facial recognition technology.

Still, some provincial privacy laws may be broad enough to help protect people against the collection and use of their biometric data, according to Janet Burt-Gerrans, the acting director and chief privacy officer with the Nova Scotia office.

The federal Department of Justice said the country's Privacy Act regulates to what extent federal entities can collect, use, disclose and retain personal information.

But that legislation does not apply to provincial or municipal police forces.

The RCMP are subject to the act, the Department of Justice said, meaning the force "can only collect personal information that relates directly to its mandate as Canada's national police force."

The department would not say if there are any plans for more robust regulations to manage the use of facial recognition technology.

Fraser said all police forces need to be more accountable for how their investigative techniques affect people's privacy.

"We've consistently seen from the police that their understanding of reasonable expectation of privacy is completely disconnected from what most of us think a reasonable expectation of privacy is, so we can't have police making those decisions."

Calgary police say facial recognition technology has worked well for them, cutting down on the time it takes to identify suspects.

Staff Sgt. Gordon MacDonald, of Calgary's criminal identification unit, said having an officer manually scroll through mug shots on a computer looking for a potential match to a suspect "would be a considerable amount of hours, if not days, trying to find a suitable match."

The system returns results within two minutes.

MacDonald said there are strict rules about how the system is run and officers only use it to compare images with mug shots.

"It's such a valuable technology we wouldn't want to do anything that would jeopardize our permission to have it," he said.

There are about 350,000 mug shots of people who have been charged with various offences in Calgary, but MacDonald said a national database would have to be created to make the system truly effective

"We just have a database that's just purely for Calgary," said MacDonald.

"Canada has such a transient population. People go from province to province and subjects of interest may appear in Calgary and they may be a resident of Edmonton. And of course our system would never find a possible match."

A national database would change that. It would allow officers in any part of the country to match images with mug shots from anywhere in Canada.

Fraser said before there is a national database, law enforcement, privacy regulators and members of the public need to develop regulations on how that system would be used. He said there's a risk of informal national systems being set up as police departments look at sharing more information.

"These sorts of initiatives are probably happening outside of view and so we need to put in place regulations before we end up with a de facto national database," he said.

Michael Arntfield, a Western University criminologist and former police officer, agrees. He said clear regulations would reassure people that police are using facial recognition responsibly.

He said without rules the door is open to private companies to offer their services to police.

"I think that would alleviate the concerns that I think people have about using a private-sector third party to compare to wedding photos that were scraped from social media accounts," said Arntfield.

Fraser said police have access to many technologies that allow them to monitor people and society needs to decide when law enforcement should be allowed to use those tools.

"They don't get to use every tool at their disposal," he said. "They get to use appropriate tools. There are intrusive technologies that need to be regulated, because they could be horrifically abused, or they could be mildly abused in a widespread sort of way that leads to a significant diminution in our privacy rights."