Anxiety pills that promise so much leave behind a hidden 'epidemic'

Addiction experts say misuse of benzodiazepines leaves older people hooked, teens high

Two weeks after her mother died, Rhonda Assoun-Gritten was looking around the 63-year-old woman's Dartmouth, N.S., apartment, opened the drawer of the night table and discovered receipts for three recent prescriptions. Assoun-Gritten didn't recognize the names of the medications, but stuffed the papers in her back pocket.

The death of Sharon Assoun on Feb. 24, 2016, had been shocking not only in its suddenness, but in its unusual nature. While babysitting that night at her son's home, she had gone down to the fridge, her daughter says, and drank a bottle of his illicitly purchased methadone.

When the toxicology report came back six months later, it pointed to the obvious. The amount of methadone, which is used to treat opioid addiction, had been within the lethal range. But the medical examiner's report also listed two sedatives in the cause of death. A third was found during toxicology tests.

It turned out that Sharon Assoun had for years been prescribed a class of drugs called benzodiazepines for insomnia and anxiety. On a hunch, her daughter showed the prescription receipts she had retrieved from her mother's home to her own family doctor.

"She put her hands on her head and put her head on the desk," says Assoun-Gritten. "'Rhonda,' she said, 'Your mother was so overmedicated she wouldn't have known, awake or asleep, if she was drinking the methadone."

Benzodiazepines have been used for nearly six decades to treat seizures, anxiety and insomnia. In 2017, more than 26 million prescriptions for benzodiazepines and related drugs were written in Canada. They include diazepam, lorazepam, alprazolam and clonazepam, and go under brand names including Valium, Ativan and Xanax.

But addiction experts have long worried about what they view as the widespread misuse and overprescribing of benzodiazepines. There is a growing push to come to grips with a problem that crosses generations, from seniors hooked for decades to the alarming emergence of Xanax abuse among teens in places like Nova Scotia.

Some are now even drawing parallels to the opioid addiction problem.

"As we start to treat the opioid epidemic and peel back that layer, the extent of the benzodiazepine epidemic that is gripping North America is going to be shown," says Dr. Selene Etches, manager of the concurrent disorder program at the IWK Health Centre, the Atlantic region's largest children's hospital.

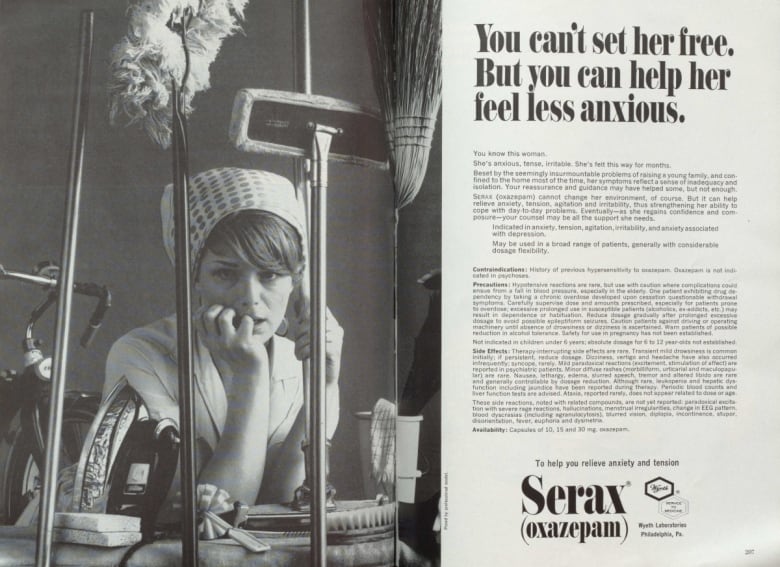

Benzodiazepines were created in 1955 by chemist Leo Sternbach. Hoffmann-La Roche marketed its first version of the drug in 1960 and launched Valium three years later.

The drugs have a number of advantages. They're effective. They also appeared to be safer than barbiturates, a predecessor used to treat anxiety and insomnia with higher risks for overdose.

But they could still be addictive.

The 1966 Rolling Stones song Mother's Little Helper described "running for the shelter" of a "little yellow pill." By the 1970s, some doctors were raising the alarm. Deep concerns about benzodiazepine-prescribing practices remain today.

"I'm as concerned about this as I am about the prescribing of opioids for chronic pain," says Dr. Samuel Hickcox, the physician lead for addictions at the Nova Scotia Health Authority. "I think we're really contributing to a problem, to be frank."

One of the patients he has treated for addiction, he says, has been on benzodiazepines for 58 years, and was prescribed the first one to ever hit the market: Librium.

In Nova Scotia, the prescribing of benzodiazepine and related drugs remains stubbornly above the Canadian average, despite some modest decreases since 2012, according to data from the Canadian Institute for Health Information. Other Atlantic provinces fare even worse. Newfoundland and Labrador is double the national average. New Brunswick's numbers are even higher.

From 2011 to October 2018, benzodiazepines contributed to 313 "acute toxicity deaths" in Nova Scotia. Nearly 80 per cent involved a deadly mix with opioids.

Doctors say benzodiazepines do have a useful role. They can prevent seizures and are an effective treatment for severe alcohol withdrawal. They offer rapid relief for acute anxiety, and can calm a person before surgery or help someone terrified of flying.

But doctors say in most cases, they should only be prescribed for short periods. Long-term use can lead to dependency and addiction. While some patients function just fine for years, for others, the side-effects include cognitive decline, dizziness and drowsiness.

"We know that in the elderly, the chance of falling or having an injury from a fall goes way up when they're on benzodiazepines," says Dr. Connie Leblanc, an emergency doctor in Halifax who is part of a campaign called Choosing Wisely, which aims to curb unnecessary tests and prescribing.

Too often, Hickcox says, benzodiazepines are so effective early on that patients lose the incentive to build resilience against their anxiety. He calls the drugs "alcohol in pill form" because they work on some of the same parts of the nervous system as booze. It's almost akin, he says, to prescribing a beer.

As tolerance to benzodiazepines grows, anxiety can return. One pharmacist told CBC News she has made "grown men cry" by refusing early refills.

Worse yet, getting off them after long-term use is hard. Cold turkey is never recommended and potentially fatal due to seizures. It is more dangerous than opioid withdrawal, experts say.

"It gets me really nervous, as a physician who works in addictions," says Hickcox.

For Steve Sepulchre, that moment of reckoning came as he writhed on the floor of his psychiatrist's office, begging for diazepam. He had lost his prescription and no one would give him more pills. Afterwards, his wife, Heather Holm, gave him an ultimatum: If he went back on benzodiazepines, their marriage would be over.

"It wasn't even a threat to leave. It was a statement of reality," she says in an interview at the couple's home in Martins Point, N.S. "Because there was no marriage with those drugs. The intimacy of marriage was not complete with those drugs."

Sepulchre's decade-long slide had started in 2001 when he visited his doctor for insomnia. At the time, he was holding down two jobs, as an aviation regulations consultant for Transport Canada, and teaching French at Acadia University in Wolfville, N.S. He was also being gnawed at by unresolved trauma from childhood.

Different drugs were tried. Later, a psychiatrist prescribed lorazepam, and eventually diazepam.

"The immediate feeling is relief," says Sepulchre, who is now 65. "That's the immediate feeling is welcome relief. It's like, now I can sleep. Huh. Now my problems don't seem so big anymore. Huh. Now I'm getting along easier with the world, the constraints of the world."

But as time wore on, the symptoms of anxiety would return. The dosage would rise. The pattern would repeat. His lock on reality was changing. Technical aspects of his contracts became too hard. It was like the people around him were at the bottom of a swimming pool, their voices distorted by the water.

He was becoming apathetic and withdrawn. His spark was gone. Friends noticed. He would write crazy things to relatives. When it all became too much, he would "freak out," sometimes breaking electronics.

After his psychiatrist died, his file was sent to a family doctor in nearby Bridgewater who issued him a blunt assessment. His dosage of benzodiazepines would eventually kill him. A new psychiatrist put him on a tapering program, one of the primary ways to get someone off benzodiazepines.

Two years in, he lost his prescription. It was as if a decade of building tension was uncorked. Images flitted through his mind like banners trailing an airplane: details of meaningless work meetings long forgotten, obsessions from childhood. His heart rate shot up.

Today, he is off all the drugs, including an antidepressant he had also been prescribed. He only takes a small dose of marijuana oil at night to help him sleep. He credits meditation and the support of his wife with saving him. Slowly, incrementally, at times imperceptibly, he says, he's found enough tranquillity to bring himself back in touch with reality.

Concerns about benzodiazepines may date back at least to the Rolling Stones' early days, but the pop culture references hardly end there. The Guardian newspaper in the U.K. called Xanax, also known as alprazolam, "perhaps the most fashionable drug in 2017's rap scene."

This came after American rapper Lil Peep, who had rapped about using Xanax and posted a video saying he had popped six pills, died of an overdose.

Grammy-nominated singer-songwriter and rapper Post Malone spelled out his drug problems in the lyrics of Better Now, released last year: "I did not believe that it would end, no. Everything came second to the benzo." The California rapper Diego Leanos is even known by the stage name Lil Xan.

It was also in 2017 that Etches, the IWK addictions doctor, stepped back and realized something startling. The number of youth she was seeing who were abusing opioids was dropping. Xanax had now become her chief concern.

Many of the young people she treats are snorting and injecting the benzodiazepine in amounts far beyond what would be prescribed. They are self-medicating for anxiety and depression, to relax, sleep, escape trauma in their lives. Others want to get high, but then continue to use to deal with the withdrawal.

Tutorials on the internet outline how to lie to a doctor to get a prescription. Many young people, Etches says, are simply raiding the medicine cabinets at the homes of families and friends. What is even more worrisome, she says, is counterfeit Xanax is being sold over the internet.

Youth who come to the IWK for addictions treatment have their urine tested. The results reveal fakes are being laced with ecstasy, amphetamines, and deadly opioids like fentanyl and carfentanil.

"We tested one youth's urine and the only benzodiazepine that wasn't present was the one that he thought he was using," she says. Some teens have even obtained take-home kits to test their drugs.

One of things that makes Etches the most nervous is the withdrawal. So significant is the danger of seizures and delirium that she hospitalizes youth going through the process.

"The cravings can last years, especially in adolescence, because the brain is developing so much."

In October, benzodiazepines were added to Nova Scotia's prescription monitoring program, which can help flag worrisome prescribing patterns or identify patients doctor shopping for drugs.

A hotline staffed by specialists to give advice to doctors and nurse practitioners worried about patients with "problematic relationships to their medications," such as opioids and benzodiazepines, could be up and running by April.

An addictions education mentorship for health-care professionals now has 300 members in Atlantic Canada. And a program launched by two Dalhousie University experts aims to help insomniacs sleep without taking pills.

At her family doctor's urging, Rhonda Assoun-Gritten launched a complaint with the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Nova Scotia against the physician who had been prescribing benzodiazepines to her mother.

An investigation showed Sharon Assoun had long been on oxazepam for anxiety and temazepam to help her sleep. But in the months leading up to her death, she had switched from oxazepam to a similar sedative, clonazepam, and then back again as she dealt with "distress" related to family issues.

Her doctor would later tell the college he instructed Assoun not to take the clonazepam once she returned to her old medication. He said he had counselled her and suggested mental-health treatment to help her deal with her issues. She declined. He reported she was coherent, clear and alert, and didn't appear overmedicated.

But not long before her death, Assoun managed to fill prescriptions for all three benzodiazepines. She told the pharmacist she needed that much. He never called her doctor to clarify.

The college of physicians concluded Assoun's family doctor had not been overprescribing. The Nova Scotia College of Pharmacists, which reprimanded two pharmacists involved, saw it somewhat differently. It noted that even using two benzodiazepines at the same time is "not a preferred treatment plan, however, it is not an uncommon prescribing practice."

"I feel really let down by the whole system," says Assoun-Gritten. "It's really sad that one phone call, just one phone call, and my mom would still be here."

If you have a story about benzodiazepines you want to share, contact richard.cuthbertson@cbc.ca