New booze labels in Yukon warn of cancer risk from drinking

Labels introduced as part of ongoing Health Canada study on attitudes and behaviours toward drinking

Yukon is a testing ground for some new types of labels on alcohol bottles, that warn of cancer risks associated with drinking, and encourage better habits.

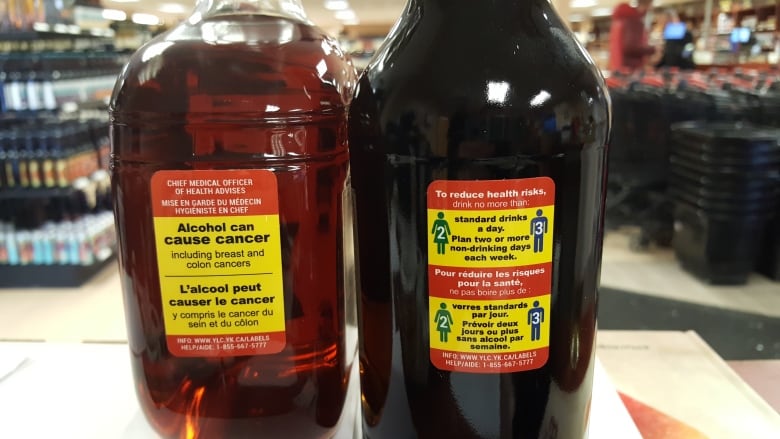

Two new labels were unveiled at the Whitehorse Liquor Store on Wednesday. They'll be affixed to all bottles and cans sold in the territory over the next eight months, as part of an ongoing Health Canada research project.

"Yukon has a chance to be a leader in Canada, as well as internationally, to demonstrate the potential benefits of labelling alcohol containers," said Brendan Hanley, the territory's chief medical officer of health.

"By seeing these labels repeatedly, and in their variety, we hope that there will be increasing familiarity with Canada's low-risk drinking guidelines."

Hanley notes Yukon tends to have higher rates of drinking, including by youth, than most of Canada, and also has relatively high rates of alcohol-related violence.

Warning labels have been used on alcohol for years, most commonly to warn against the risks of drinking while pregnant. The Yukon labels are unique in pointing to cancer as another risk.

"Alcohol can cause cancer including breast and colon cancers," reads one of the labels.

Another label focuses on healthier habits, by advising against drinking more than two or three standard drinks per day and encouraging people to "plan two or more non-drinking days each week."

The labels are being introduced as part of a Health Canada research project, focused on alcohol use in Yukon and the N.W.T. The new labels are only being used in Yukon right now.

'People want more information'

"The labels are relatively larger in size to make them easily noticed and read. They're full colour with a bright yellow background and red border so that they stand out on the container, and they have messages that provide new information," said Erin Hobin, the project's lead researcher.

She says when liquor store customers were surveyed last spring in Yukon and the N.W.T., as part of the project, they were asked if they wanted more warning labels.

"We had a resounding 'yes.' They would like more information. And that's consistent with research across Canada — people want more information about alcohol, on containers," Hobin said.

The new labels, she says, "reflect what consumers said they wanted to know."

Researchers will try to assess whether the labels have an impact on consumer attitudes and behaviours in Yukon. Next spring, they'll again survey liquor store customers and compare new findings to survey data from last spring.

"We'll also be looking at sales data to see if sales of alcohol overall, as well as different types of alcohol, shift before and after the labels," she said.

The researchers can also compare survey and sales data from Yukon with similar data from the N.W.T., where the labels are not being used.

Influencing behaviour

Hobin says the researchers don't expect warning labels to stop people from drinking. The goal, she says, is to influence consumers' attitudes and behaviours in the "broader sense," and make labels part of a larger public health strategy.

"Do labels increase awareness and knowledge of the health risks of drinking alcohol? Do they strengthen people's intentions to perhaps re-think their drinking, or reduce their drinking?

"So I think that idea of, 'do labels work?', we have to think a bit more broadly."

Hobin applauded Yukon for having the "courage" to try out the new labels, and said the territory can be "a real leader" in Canada.

Hanley agrees.

"If we can demonstrate an effect, there is potential for some important policy changes not just locally, but nationally and internationally, to address responsible alcohol consumption," he said.

"Are we able to shift that curve, shift the attitudes and habits of our population?"

With files from Mike Rudyk