Flea market find inspires new First Nations art exhibition in Yukon

Stories Embodied showcases the work of the late carver Kitty Smith, 'a revolutionary woman of her time'

Krista Reid, culture and heritage co-ordinator at the Kwanlin Dün Cultural Centre (KDCC) in Whitehorse, got the call last summer. Her friend had been to a flea market in Edmonton, where an antique dealer was selling something very special.

"She said, 'there's a Kitty Smith carving there.' I said, 'what!?'" Reid recalled. "And so we had to have it."

Reid secured permission from the KDCC to purchase the $1,200 poplar carving, then had someone pick it up while they happened to be in Edmonton, and bring it to Yukon.

The undated carving, called The Wolf Man, prompted Reid to curate a new exhibition of Smith's pioneering work. The exhibition opened at the KDCC on Friday.

"I was just so inspired by her," Reid said. "I just wanted to be able to bring life to her story, somewhat."

Smith was born in about 1890 to a Tlingit father and Tagish mother. She began carving in the 1930s, sometimes in collaboration with her husband, Chief Billy Smith.

"This was a Yukon commodity — people came from all over the world, and Kitty sold these," Reid said.

"At that time, women weren't carving. But she was providing for her family this way, she was sharing the culture with strangers, she was educating people on Northern First Nations communities — and in the 30s!"

"She's a revolutionary woman of her time, and still is someone to aspire to today," Reid said.

'These stories are true'

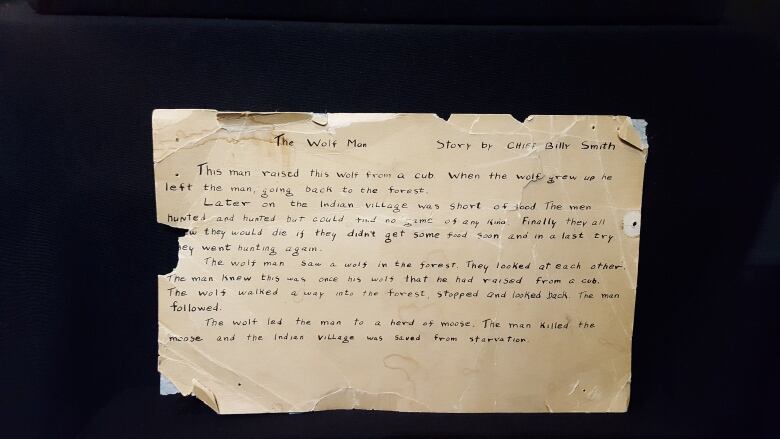

Reid says when The Wolf Man was first delivered to the KDCC, she was so entranced by it that she didn't pick it up for a while. When she finally did, she found a hand-printed label affixed to the back, with thumbtacks.

It tells the story of a man who raises a wolf cub then sets it free. Later, when the man's village is starving, he spots the wolf in the forest and the animal leads him to a herd of moose, "and the Indian village was saved from starvation."

"Story by Chief Billy Smith," the label says.

"This just says, each carving had a life, had a story, had a meaning for her and Billy. And they shared these with everyone," Reid says.

"They brought to life the histories, the traditional stories, how things came to be."

Reid says she gets irritated when people refer to First Nations creation stories as "myths" or "legends".

"Because it really has that feeling that it's not true. And these stories are true, and Kitty will tell you — it's a true story, it happened!"

Looking for more

There are eight other carvings included in the new exhibition, entitled "Stories Embodied". There's also a doll, hand-sewn by Kitty Smith.

Three of the carvings are on loan from the Champagne Aishihik First Nation, and five are part of the Yukon government's permanent art collection.

Reid hopes the exhibition will lead to other discoveries, if people have their own Kitty Smith carvings stashed away at home. She says Smith sold a lot of work in the 1930s and 40s.

"If anyone has any of these carvings, I would love to include them," Reid said.

Reid is also hoping some of the Smiths' relatives and descendants come see the work, and share any memories they have. She's already spoken to some who remember "the smell of poplar in the house" when Smith was carving.

"I can't wait to learn more and more as people come in," Reid said.

The exhibit Stories Embodied will be on display at the KDCC until Sep. 29.

With files from Sandi Coleman