N.W.T. resident spots 'awe-inspiring' landslide that created a new lake

Northwest Territories can expect and anticipate more events as permafrost thaws, says scientist

A power technician from Inuvik, N.W.T., says a massive landslide that pulled up chunks of debris "the size of houses" is blocking a waterway west of the Mackenzie River, creating a lake.

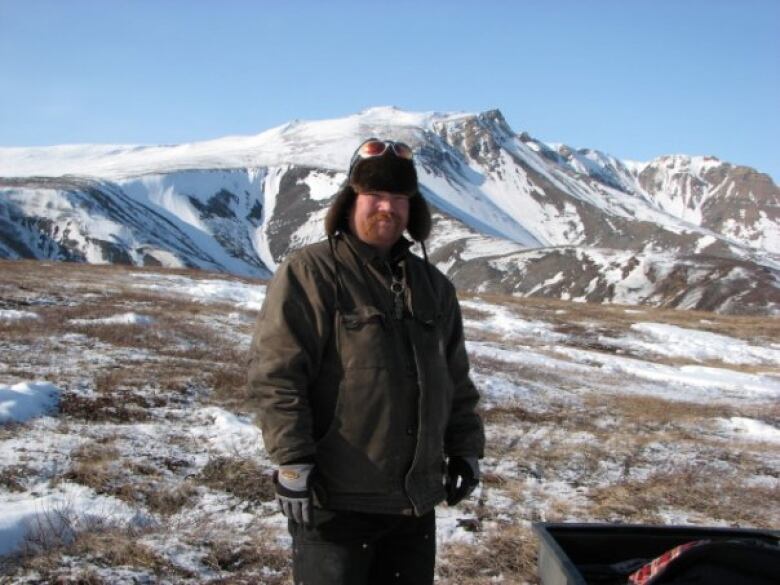

Eric McLeod said he spotted the scene last week in the Johnson River, which is located between the communities of Wrigley and Tulita, N.W.T., and connects to the Mackenzie River.

He estimates the landslide is about five kilometres from where the two rivers meet.

"I've seen quite a few of these slides in the past and normally it's mostly mud and debris," McLeod said, "But in this case there were actually boulders … and there were still trees on them."

"The amount of earth that moved was just awe-inspiring."

McLeod has spent 15 years travelling to remote locations for his job. He credits a pilot with Great Slave Helicopters for pointing the scene out to him while they were flying over the area on March 1.

Landslides increasingly becoming common

Dennis Rusch, the helicopter company's base manager for the Sahtu region, said he discovered the landslide in late August or early September 2017, before any snow had fallen.

He estimated the blockage in the Johnson River stretches 250 to 300 metres wide and is at least 300 to 400 metres long.

While it's the widest landslide Rusch has ever seen, it's not the first.

"We're seeing these slides quite a bit now, all over the mountains in the Sahtu area," he said, adding they're creating lakes of all different sizes.

Steve Kokelj, a permafrost scientist with the Northwest Territories Geological Survey, hasn't been to the Johnson River landslide himself, but said these kinds of events are common in the Northwest Territories.

That's because much of the Mackenzie Valley contains permafrost.

"As the permafrost warms, a lot of slopes can lose stability and you can have landslides," he said, adding they can come in different forms.

The upper and lower Mackenzie Valley, including the Johnson River, are prone to shallow landslides, he said.

Kokelj said data shows the level of activity and size of these "disturbances" are increasing in many parts of the lower Mackenzie Valley and throughout the N.W.T.

"As the climate warms and permafrost temperatures rise and permafrost thaws, these types of phenomena will become more common," he said. "We need to expect that and anticipate that."

Changes noticed by area residents

Wrigley resident Charlie Talley, 62, isn't surprised by the increasing number of landslides in the territory.

He spends a lot of time on the land and has seen these events happening in the region for some time.

But over the last five years, he's noticed a "big change."

"I think it's impacting the rivers. It's dropping every summer. The water's getting lower and lower," Talley said. "There's all kinds of sandbars that you've never seen before. Even from here, there must be about 30 little sandbar islands."

While Talley said there's little he can do about them, landslides are taking a toll on communities.

"It is impacting our culture, like hunting and fishing," he said. "The riverbed is changing every year."

Chris Burn, a geography professor at Carleton University in Ottawa, researches permafrost and ground ice in the Yukon and Western Arctic.

"That's a big problem for the communities of the Western Arctic because they rely on groceries coming, they rely on shipment of materials, they rely on propane, they rely on that road being open," Burn explained.

He said the number of landslides in the areas he's examined — in the Mackenzie Valley, the Beaufort Delta and the Peel Plateau — has increased since the 1990s.

In September 2009, 25 landslides were recorded in the Caribou Hills, north of Reindeer Station, in the Northwest Territories, he said.

In September 2017, approximately 80 landslides occurred in the same spot.

Both years had multiple weeks of rainfall, followed by a few days of heavy downpour.

"But before that, there hadn't been very many landslides reported for many, many years," said Burn.

He attributes the change to "climate wetting" — something he says people haven't been thinking about as much as warming and thawing permafrost.

"The way that climate warming works, it's associated also with more moist, warm air from the south coming up to the North," Burn said. "When that warm moist air comes up more commonly, then it brings more rainfall."

'Potential for that dam to breach'

When warm weather arrives in the N.W.T. again this spring, it could cause the debris from the Johnson River landslide to move.

Kokelj said residents should be cautious of travelling in that area or similar environments prone to landslides.

"There is of course the potential for that dam to breach and then a flush of water to go downslope," he said. "The amount of material is so great that likely … it would take some time for the stream to cut a channel. But certainly that is a risk that I think people need to be aware of."

Kokelj said more investment is needed in permafrost research in order to understand the risks that events like landslides can pose for communities and infrastructure in the North.

"It's a discipline that I think has really grown in relevance," said Kokelj. "The capacity to be able to engage and develop knowledge in this field is important."