Here's why men are bearing the unemployment brunt of the economic slowdown

Men drawn to volatile industries like construction, while women dominate health, education, service

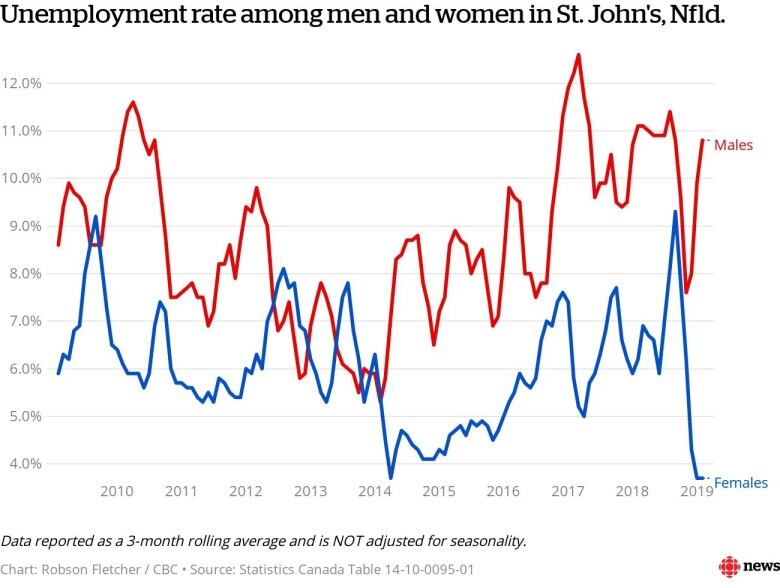

The unemployment rate in Newfoundland and Labrador is trending downward, but one pattern that persists — and stands out from a national perspective — is the gap in the jobless rate between men and women.

According to February numbers from Statistics Canada, the seasonally adjusted unemployment rate for males ages 15 to 64 was 13.9 per cent, versus 9.1 per cent for females. That's a difference of just under five percentage points, and there are signs the gap is widening once again after nearly merging for a brief period last year.

"The difference here is quite startling," said Memorial University economist Lynn Gambin, who keeps a close watch on the labour market.

And the picture is even more eye-opening in St. John's, where the unadjusted numbers for February show the unemployment rate for women is less than four per cent, while the rate for men is just under 11 per cent.

Volatility in construction sector

It's in stark contrast to the Canadian numbers, where there is only a slight difference — less than one per cent — in the male-female unemployment rate.

"Our gender gap is much higher than what we see in Canada as a whole," Gambin stated.

So why is there such a variance?

Consider that 90 per cent of those working in the construction industry are male, and major project construction —along with oil and gas — has fuelled the province's economy for the past decade or so.

In 2013, for example, major project spending topped $9 billion, the most by far of any province in Atlantic Canada, and Newfoundland and Labrador was often the envy of the country when it came to capital investment.

This coincided with a housing boom, driving a construction bonanza that again employed mostly men.

So there was a brief period where the unemployment gender gap nearly disappeared.

Megaproject completions

But that all changed after the collapse in oil prices in late 2014, and a multitude of other factors came together to shake up the labour market.

The Hebron platform, which employed more than 5,000 workers at peak construction, is now producing oil in the offshore. Vale's massive nickel processing plant in Long Harbour, Placentia Bay, is also complete, while construction on the Muskrat Falls hydroelectric project is more than 96 per cent complete, according to the latest update from Nalcor Energy.

So the heyday of simultaneous megaprojects in the province is long past, and the data shows the unemployment gender gap widened substantially between mid-2016 and mid-2018, with male unemployment nearly 10 percentage points higher at times.

And the housing boom has also collapsed, with just over 1,000 housing starts last year, down from a historic high of nearly 4,000 in 2012.

The disappearance of good-paying rotational jobs in Alberta's oil industry has also eliminated a large segment of the labour market dominated by men.

So with mostly men working in volatile industries like construction, it's no surprise there is a notable gender gap in the unemployment rate, said Gambin.

"When there's a downturn it tends to be in construction and skilled trades and those areas that we see job losses happen most drastically. And those are areas where we have predominantly male employment," she said.

Ongoing projects

But the construction sector is not completely silent.

There are currently nearly 800 people working on the West White Rose concrete gravity structure oil platform in Argentia, according to Husky Energy, and Grieg NL is ramping up construction of a large aquaculture project based in Marystown.

And as of December, more than 1,900 people were working on the Muskrat Falls project, 85 per cent of which were male. That's down from roughly 5,300 in early 2016.

And with oil companies pledging to spend some $4 billion in exploration in the coming years, it's possible that more major projects may be on the horizon as offshore production is poised to grow.

Meanwhile, women represent a large majority of those who work in public service jobs such as health (80 per cent) and educational services (71 per cent), where there is, generally, job stability.

"You've got long-term contracts, collective bargaining. So making job cuts at a moment's notice is more difficult," said Gambin.

And with the oil and mining sectors, both of which are big job creators in the province, moving more and more towards automation, it's unlikely the gender gap will disappear anytime soon.

The unemployment rate is compiled by determining the number of people of working age who are actively seeking work, and measuring it against the size of the labour force.

What is doesn't measure is those who have given up looking for work, or have moved to another province in search of better opportunities.

"If there were more men who have left the province to look for work elsewhere or have just given up and are not seeking work anymore, then that kind of is hidden behind that figure and it could be worse," said Gambin.

According to Statistics Canada estimates, Newfoundland and Labrador had a net loss of 3,000 people to Ontario, Alberta and Nova Scotia in 2017-18.

Four years ago, the province recorded a small net gain from those provinces.