New Brunswick should be 'nervous' about future outmigration

UNB demographer Michael Haan says more need to be done to understand why young people are leaving

Young people move — all the time. What’s different now, however, is that there’s a glut of young people entering its high mobility years in New Brunswick and as a demographer I think we should be very nervous.

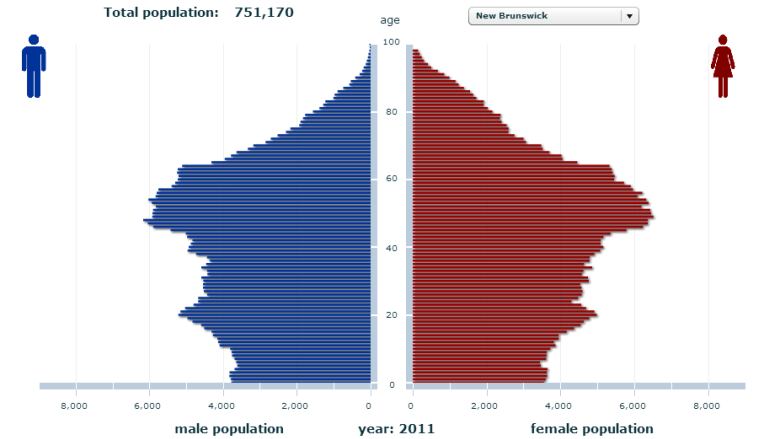

Take a look at the age pyramid from the 2011 Census, which shows how the Canadian population is spread out across age groups.

Notice that the pyramid has three bumps on either side. The first, and largest, is the baby boom (those born between 1946-1965), with a peak age of around 50 in 2011.

The second largest is the baby echo (1972-1992), or mostly the children of boomers. Finally, the small bump at the bottom of the pyramid is what I like to call the "echo of the echo."

That little bump at the bottom is the reason daycare and kindergarten enrolments are up these days.

Each of these groups is interesting in its own right, but I want to focus on New Brunswick’s baby echo or that middle bulge. Check out the following figure from Statistics Canada, which plots the propensity of Canadians to move, both inter-provincially (the blue lines) and overall (shown in red) by age.

Look at the spike in migratory activity that occurs when people hit their mid 20s to early 30s. What this suggests is that if someone is going to move, this is when they will likely do it.

It certainly happened this way in the past, and to profound effect. As baby boomers moved through their migratory years in the late 1970s to early 1990s, the populations of Calgary, Halifax, Saskatoon, Toronto and many other urban centres more than doubled.

Sure, immigration helped, but the main driver of growth in each instance was the result of the trend that you see in Figure 2 above. For New Brunswick, roughly 150,000 baby boomers left the province as they passed through these high mobility years and only a fraction ever came back.

Now, it’s New Brunswick’s echo’s turn to move.

And it’s not just our echo that moves. Since 2008, every province east of Saskatchewan has seen a fairly steady outflow of people age 15 to 24.

Although there are some minor discrepancies, as you head east the loss becomes greater. About 25 people age 20 to 24 left Newfoundland and Labrador this week.

Thankfully, we’re not Canada’s easternmost province; we only lost about 15 young people last week.

Their parents received tax breaks, because we felt it was important to ensure that children could be well taken care of.

We embraced the notion that it takes a community to raise children, and we invested accordingly.

Now, as the time comes for them to pay us back, they leave. They’re heading to both usual (Alberta and Ontario) and not-so-usual (Saskatchewan and the Yukon) destinations.

I want be clear: I’m not blaming the baby echo for leaving, but I do want to understand them.

I’m also not blaming government for outmigration, because there are quite a few smart people in charge.

They face tremendous pressure from the electorate to develop polices with a retention angle to them. Tuition credits, job fairs, skills development, the One Job Pledge, are all underwritten by a pressure to do something, anything, about our dismal youth retention rates.

Although some outmigration is inevitable, I believe the rates could be improved by learning more about how young people think.

How do people choose where to go?

Again, the knee-jerk response is that they go where the jobs are, but my hunch is that the full answer appears to be a bit fuzzier — at least it is to us, which I’ll return to momentarily.

Will the baby echo really move because of jobs?

What I consistently find is that young people make decisions that I, as a middle-aged man, see as (often disturbingly) vaguely informed.

The one thing that nearly all young people, at least here in New Brunswick, are resolute about, however, is that, whatever they do, they won’t do it here. When I ask young New Brunswickers about how many of them plan to be here in five years, it is not atypical to only see about a quarter of all young people raise their hands.

Not every exit plan reaches fruition, but many do, and that is what 15 people per week translates to.

Clearly, we need to have a serious discussion about what our young people want and need, because something is turning them off of this place.

This is something that government can’t do alone; it’s something we all need to be talking a lot more about. It’s true that retention decisions are made at job fairs, but they’re also probably made at the kitchen table.

Given how little we seem to know about how our young people think and make decisions about where they’ll live, maybe it’s time we collectively start a conversation with them?

Why wouldn’t we formalize programs in elementary and secondary schools that talk to young people about how they make decisions?

What weight does a 23-year-old person give to housing affordability, traffic jams, spousal employment and the price of natural gas? What are the time horizons for which young people seek employment stability?

Does the phrase, "New Brunswick is a great place to raise a family," mean to the baby echo at this point in their lives? I’m guessing it isn’t the same as it does to a 40-year old.

So, now that we know what probably doesn’t motivate the baby echo, we could try to learn more about what they hold dear at this moment because this is when they’re making the (often final) decision of whether or not to stay in New Brunswick.