Not the year to die: Families denied final goodbyes may suffer prolonged grief

'We couldn't touch her. We couldn't hug her. We couldn't do nothing,' says daughter of woman who died

"Mom, we're all out here. Your children are out here."

When Patricia Joncas spoke those words to her dying mother, Katherine Davis, last month, Davis was peering through a window.

Davis suffered a stroke Jan. 18 at the Shannex Parkland nursing home in Saint John.

Because of a COVID outbreak there, visitors were banned.

That left Joncas and eight of her sisters out in the cold.

For two days, they kept vigil outside their mother's first-floor bedroom.

A 10th sister, in Halifax, was sometimes able to join them by conference call.

"We could see every bit of mom," said Joncas. "They set up a phone inside her room so that she could hear us. We hope she could hear us."

"It was heart-wrenching, to look through that glass and just watch her breathe."

"That's all we could do. We couldn't touch her. We couldn't hug her. We couldn't do nothing, except tell her how much we loved her. That was it."

Late in the afternoon of Jan. 19, the family was told Davis could have a single visitor.

Whoever got the spot would have to be supervised by a nurse at all times. The visitor would be fully dressed in a mask, shield and gown, and willing to accept the visit could only last 30 minutes.

The sisters decided Patricia would go, and that presented another kind of agony.

After losing precious time on two changes of PPE on her way in, Joncas tried to say goodbye on behalf of everyone who couldn't come in.

"I gave her 10 kisses, one for each of us girls," said Joncas.

"I was so thankful to sit there for that 20 minutes and just touch her and kiss her. It's something I'll never forget."

Davis, who worked for 21 years at St. Vincent's Convent in Saint John, died the next afternoon.

The family loved coming together for weddings, birthdays and baptisms. Joncas said that's how they celebrated life.

That's why the funeral's on hold.

They can't bear the idea of leaving out anyone who can't enter the province — or can't attend without breaking the 25-person limit on funeral gatherings.

"There are 22 grandchildren and 24 great-grandchildren," Said Joncas. "And we're a close family."

This means there's been no chance for the family to gather and reminisce about Davis's fondness for bingo or shopping.

Condolences, but no

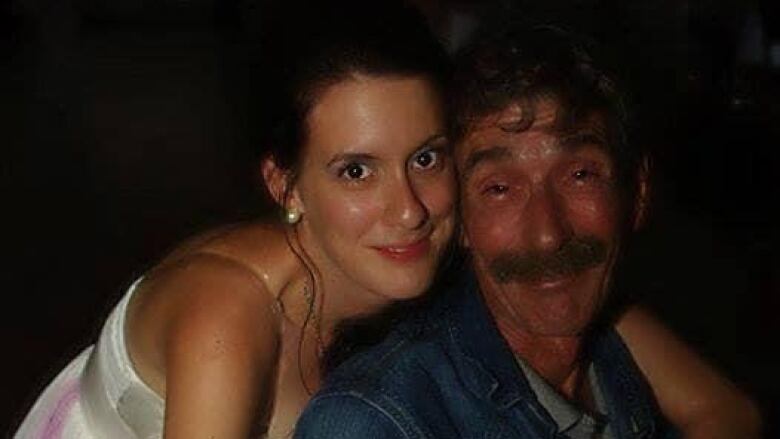

Kristen Brewer got a hard no last week when she asked for permission to enter the province for her father's funeral.

Brewer lives in Halifax but grew up in Saint John. At 33, she's already suffered profound loss.

Cancer took her 36-year-old sister in 2016 and her mother a few years later.

Ten days ago, her father died.

Steven Brewer's death was unexpected, she said, and still feels surreal because she's far away.

Brewer had a plan to self-isolate at her father's home and was happy to take a COVID test.

The email she got back from the government expressed condolences, but flatly rejected her request.

She was told there are no exemptions for end-of-life visits now or entry into the province to attend to the deceased or attend a funeral.

Brewer said she's caught in a loop of anxiety and anguish, and her brain won't turn off at night.

"A lot of it right now is how can I get there? What can I do to get there," she said.

"Aside from that, the rest of it is just impossible. I have to overcome one hurdle in order to move to the next."

Brewer said she can't even begin to mourn.

"And that's very, very difficult, especially when I've already lost so many people," she said.

Palliative care expert predicts 'epidemic of complicated grief'

Three decades before he became the Canadian Research Chair in Palliative Care at McMaster University in Hamilton, Hsien Seow lost his mother to cancer.

He was 10 when he stood at her hospital bed and said his final goodbye.

"I'm telling you, no matter what, there are things you can only say when the time is right," said Seow.

He's convinced people denied the time to be with their loved one in person are going to feel regret, and may have more difficulty coming to peace and acceptance.

"I think we are going to see an epidemic of people with complicated grief," he said.

"And the scars of that will manifest in many different ways: depression and anxiety, but also, just sadness."

Prolonged bereavement disorder

Prolonged grief, or persistent complex bereavement disorder, is recognized as a syndrome by the American Psychiatric Association.

Core symptoms include intense feelings of yearning and a preoccupation with the deceased that doesn't fade over time.

"Maybe six to seven per cent of those who are bereaved, they don't seem to be able to instinctively find their way," said Natalia Skritskaya, research scientist at the Center for Complicated Grief at the Columbia School of Social Work in New York.

Skritskaya said different organizations have set different benchmarks for how long it should take to be well on the road to recovery, from about six months to a year.

"But if it's longer than a year and the person is still struggling with intense grief, those are the people that we would label now as having prolonged grief disorder and those are the people we are trying to help," she said.

'Isolation is the worst'

After losing a teenage son in 2012, Pamela Pastirik turned her attention to helping New Brunswick families cope with loss.

Pastirik is a nurse educator at the University of New Brunswick and a driving force behind the non-profit NB Copes, which aims to connect and engage bereaved people through art, music, mindfulness and peer support.

She, too, is worried about how much and how long the pandemic has disrupted rituals and traditions associated with grieving and healing.

For families who can't move ahead with large gatherings, her advice is to try something smaller if it can be done safely.

She also encourages people to connect with others who have lived through similar experiences.

"We feel isolation is the worst thing ... for somebody that's grieving," she said.