Richard Oland homicide scene could have been better guarded: officer

Murder retrial of Dennis Oland in his father's 2011 bludgeoning death set to resume Tuesday in Saint John

The Saint John police officer who guarded the Richard Oland homicide scene after the discovery of the multimillionaire's body says in hindsight, he "probably would have done things differently."

Const. Duane Squires, who had been with the force for about five years on July 7, 2011, acknowledged under cross-examination Friday at Dennis Oland's murder retrial that about 19 officers — all senior to him — went in and out of the blood-spattered office.

He said it was his first time guarding a homicide scene and he wasn't given any instructions by any superior officers. He had not received any specific training on the topic and was unaware of any protocols on the issue, he said.

- On mobile? Follow the live blog here

"You were essentially left all on your own to figure out what to do, is that fair?" asked defence lawyer Alan Gold.

"I guess I could agree with that statement," said Squires.

Oland, 50, is being retried for second-degree murder in the bludgeoning death of his 69-year-old father.

A jury found him guilty in December 2015, but the New Brunswick Court of Appeal overturned the conviction in October 2016 and ordered a new trial, citing an error in the trial judge's instructions to the jury.

A mistrial was declared in his jury retrial and the case is now proceeding by judge alone.

In pre-trial documents, the defence advised Court of Queen's Bench Justice Terrence Morrison they intend to argue "that the [Saint John Police Force's] investigation into the homicide of Richard Oland was inadequate and will also seek to impugn the conduct and credibility of various SJPF officers involved in the investigation."

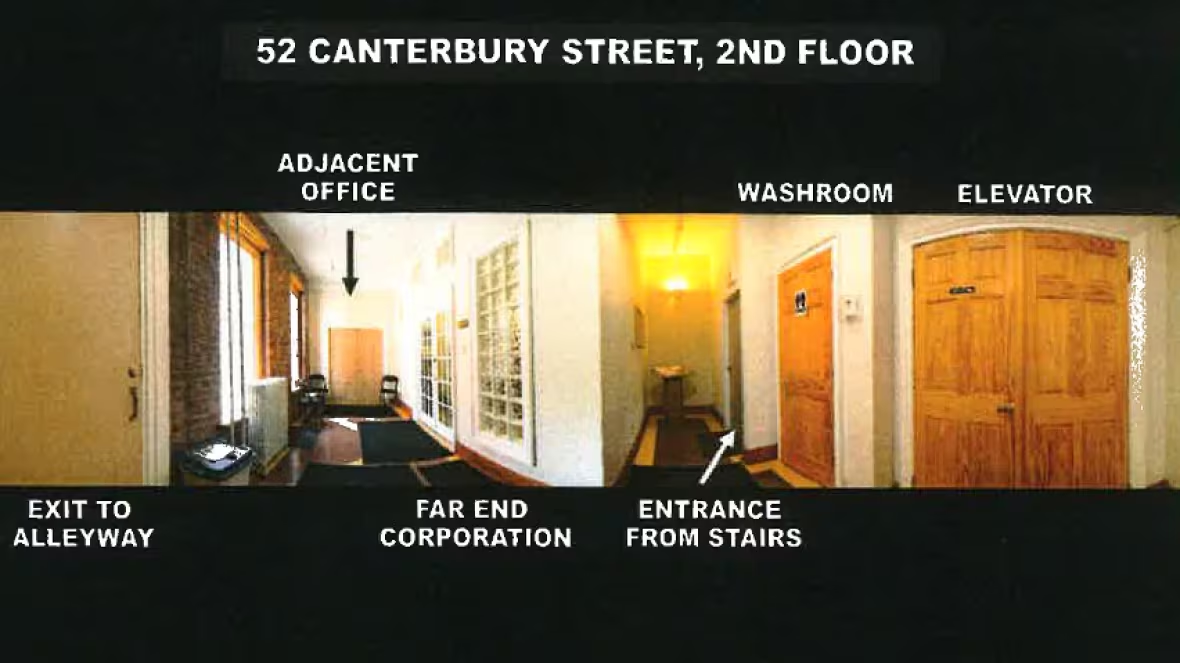

Squires was one of the first officers to arrive at the scene that day. He was a few blocks from 52 Canterbury St., when the 911 call came in around 9 a.m. for a "male, not conscious, not breathing."

As he approached the elder Oland's second-storey investment firm office, Far End Corporation, he was struck by the "distinct smell of death, or blood," he testified.

"It's a distinct pungent odour. It's not a good smell, doesn't give you a good feeling when you smell that."

He knew CPR wouldn't be required, he said.

The victim, who was face down on the floor, had a "severe gash" on the back of his head, said Squires.

A graphic photo of Oland's body in a pool of coagulated blood was displayed on a large screen in the courtroom. Crown prosecutor Jill Knee later apologized for not warning Oland family members and citizens in the public gallery before projecting the image.

Squires said he initially thought it might have been a suicide, given the extent of the damage to Oland's head.

Still, he and fellow Const. Don Shannon quickly checked the office for other victims or a possible suspect before exiting to the foyer, being careful not to touch anything, he said.

Squires told the court he believed the crime scene was only where the body and blood were located.

"When you're in the foyer, is it in your mind that you know, a fingerprint here, a little speck of thread over here could explain what took place here? Was that kind of thought in your mind?" asked Gold.

"I would say now, not as much as it should have been," replied Squires.

He documented the names of officers who came and went and the times. Some of them were there for several hours, but did not note where they went, what they did or what they said, he said.

"If this was to happen now, would I probably have done things different after being asked questions by the defence for the third time now? I probably would have done things different than the day of."

The trial is scheduled to resume on Tuesday at 9:30 a.m. It's expected to last four months.

Scalp condition, 'touchy-feely' ways

The defence team started to lay the groundwork for its case Thursday, asking the victim's secretary a series of seemingly inconsequential questions.

Maureen Adamson confirmed her 69-year-old boss had a scalp condition, wore hearing aids, and was a touchy-feely close-talker.

Toronto-based lawyer Michael Lacy didn't dwell on any of the issues and hasn't pieced them together for the court yet, but they're all related to a key piece of the Crown's evidence against Oland — a blood-stained brown sports jacket.

Adamson testified Oland was wearing a brown jacket when he visited his father at his office on the night he was killed, July 6, 2011.

She left the two alone together and the next morning, she discovered her boss' body lying face down on the floor in a pool of blood. He had suffered more than 40 wounds to his head, neck and hands.

The brown jacket, which was later seized from Oland's closet, had four areas of blood on it and the DNA found in each of those areas matched his father's profile, Crown prosecutor Jill Knee told the court during opening statements earlier this week.

The defence contends the "miniscule" bloodstains were the result of "innocent transfer."

Lacy asked Adamson about the elder Oland's scalp condition. She said she occasionally noticed little cuts on his head that would sometimes bleed.

Oland was hard of hearing and would sometimes lean in when he spoke to people, she agreed.

He tended to put his hands on people when he spoke to them, she said.

During Dennis Oland's first trial in 2015, the defence suggested the blood from his scalp could have gotten onto his hands and transferred onto someone's clothing.

His lawyer also asked Adamson Thursday about some police photographs of the crime scene, including a close-up of a black TV remote control on the floor in the blood-spattered office. In the photo, the remote is face-up. Another photo shows a remote on the floor, face-down.

Adamson said she couldn't confirm they were the same remote control. She noted the office air conditioner also had a remote.

Lacy pointed out both photos had a yellow extension cord in them, implying they were of the same remote.

He asked whether she was careful not to touch or disturb anything in the crime scene after she made the grisly discovery that morning, rushed out for help and re-entered with a man from the printing shop downstairs. She said they were both careful.

The remote for the air conditioner was grey and was usually kept either on or near Oland's desk because he sat right in front of the AC, said Adamson.

Lacy showed her another photograph, taken on July 11, four days after Oland's body was discovered. It depicts what appears to be a remote near the coffee machine. In a July 7 photo of the same area, no remote is present.

During the 2015 trial, the court heard issues about the police investigation, including officers entering the crime scene without wearing protective gear to avoid contamination and using the washroom outside the office for two days before it was forensically tested.