A startling reality: Hacking democracy easier than you think

Elections can be hacked 3 ways

It's hard to imagine that people thousands of miles away are able to sit at a computer and change the course of an election.

But as we've seen in the United States, that's not just a troubling concept, it's a startling reality that has profound implications for voters, politicians, political parties and the media.

When it comes to Canada, most experts agree it's not a matter of if or even when (we experienced some limited interference in 2015), but of how badly nation-states, organized crime, activists and thrill seekers will want to sow chaos, confusion and manipulation.

How you hack democracy

There are three primary ways to hack a modern election process.

The first is to target the electoral system itself, by, for example, finding and exploiting software or hardware vulnerabilities in voting machines.

In addition to trying to hack voting machines, attackers often attempt to gain access to voter lists in order to send disinformation about voting location, documentation requirements or other misdirection in an attempt to suppress the vote.

Canada experienced this in the past in the form of targeted robocalls. In the future, it will include fake election information emails, calls and even traditional mail.

The second way you hack a democracy is by attacking the political parties to gain damaging information for use in blackmail or to embarrass a candidate or party.

This is what happened to the Hillary Clinton campaign in the 2016 presidential election after the campaign chairman John Podesta fell victim to a fraudulent email known as a phishing attack. In addition to stealing information, attackers may also try to embarrass political parties by defacing websites or by damaging the IT systems they use to run a campaign.

Easy targets

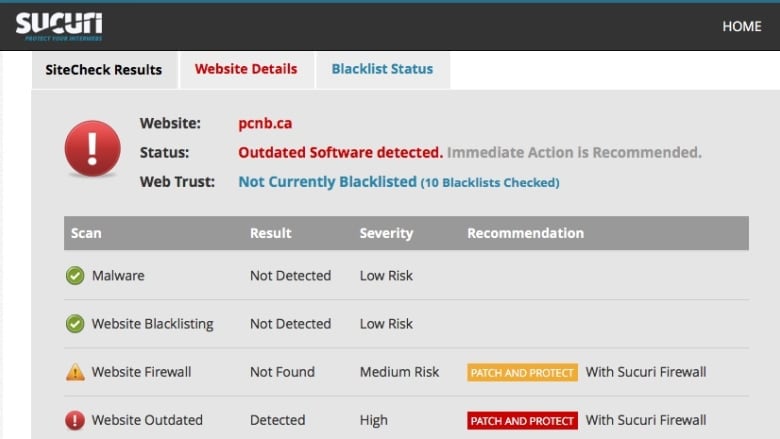

Attacking politicians and political parties is trivial. Often their political email systems and websites are not properly secured or updated, making it relatively easy to hack.

It's important to note that political parties are not protected by cybersecurity teams within government. It's also extremely difficult to get elected officials to pay attention to the security warnings from government cybersecurity experts.

The third and final major way to hack an election is by hacking minds.

This involves the use of sophisticated propaganda either directly targeted at voters via fake social media accounts or targeted at media in the form of fake leaks of information or a false sense of voter sentiment and preference.

Securing democracy from digital threats

The first step when tackling a complex problem is to admit it exists and thanks to a new report by the Communications Security Establishment and a separate report by an expert team led by the University of Oxford, there's plenty of evidence that government is waking up to this online threat.

The second step is to realize that everyone from voters, to politicians to media have a role to play in defending our democracy from foreign hacks.

For voters, it means paying more attention to facts and being able to spot and avoid so-called fake news.

For politicians, it means investing in security training and tools for their parties and listening to government experts as elected officials.

Be skeptical of leaks

For media, it means being much more skeptical about digital leaks of information and taking time to confirm stories rather than being the first to publish.

Finally, protecting democracy and elections from hacking means taking a careful look at any new e-voting (online or voting machine) approaches and questioning whether the risks are worth any perceived gains or whether the risks can be appropriately mitigated so that voters can have full faith and confidence in the electoral system.

For now, this means that until cybersecurity and digital identity improve dramatically in Canada, we all should be extraordinarily wary of any proposals for online voting over the internet.