It's been 72 years since Thomas Falls was killed in custody. His family says it's time for justice

Relatives of Black WW II vet want people to know the truth about what happened in Montreal's Bordeaux jail

When retired lance-corporal Thomas Falls died in solitary confinement at Montreal's Bordeaux jail in 1948, 10 days after being severely beaten by police, there was no public outcry and little newspaper coverage. His family and members of the Black community were outraged, but there was little they could do about it.

Seventy-two years later, as people are speaking out loudly against racism and police brutality, Thomas Falls's great-grandson, Gabriel Falls, says the family would like to use this moment to clear his great-grandfather's name.

"Definitely, his story needs to be heard because we're in a time right now when people are listening," said Gabriel, 29. "Unfortunately, in his time, when he was killed, people didn't care as much or didn't give it attention at all."

Thomas Falls was 32 in September 1948, a strapping ex-soldier working as a railway labourer, a common job for Black men in Montreal at that time. He had just taken the examination for admission to the CNR Porters' Association, which would have been a step up the wage ladder.

His wife, Rose, was undergoing treatment for what today we would call postpartum depression. She'd been taking care of their four children, all under the age of six, alone for most of the war. Her husband, a lance-corporal in the Royal 22nd Regiment, known as the Van Doos, had been stationed as a military police officer in England from 1939 to 1945.

One night in early September, Rose was in hospital, and their four children were staying with relatives. Falls was alone, and he agreed to go with a friend to a bar in east-end Montreal. A witness told the family he drank too much and got into an altercation over a song playing on the jukebox.

"There was a scuffle," his son, Thomas Falls Jr., recalls being told, and two police officers arrived to arrest his father.

When the two approached, Falls refused to go with them.

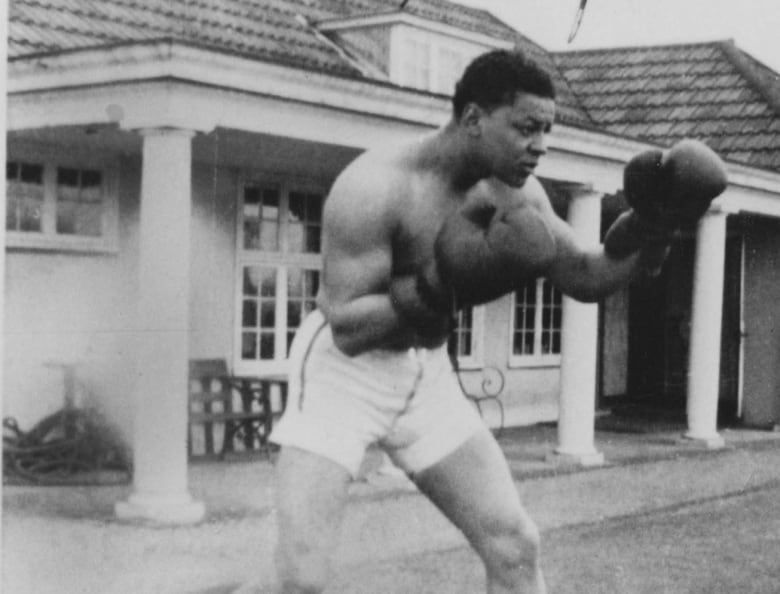

"My father was a big man," said Thomas Jr. "He'd been a boxer in the army, so these two guys got scared and called for help. The paddywagon came, and they worked him over in the van. And it was history after that."

Falls was taken to Station 25 in downtown Montreal. When he appeared in court a few hours later, his family says it was clear he had been beaten up.

"His face looked like raw roast beef," his son, Thomas, Jr., was told.

The notorious Bordeaux jail

Falls was then taken to Bordeaux jail.

A few years later, Peter Gzowski, writing in Maclean's magazine, described the provincial detention centre this way: "The Montreal prison at Bordeaux, more commonly called Bordeaux Jail, is a hulking four-storey grey building shaped like a six-pointed asterisk on the west side of Montreal Island."

He went on to say that "the ugliest fact about this ugly institution is that a man may be imprisoned in it without committing a crime, and without being tried by a court."

That was the last the family of Thomas Falls ever saw of him. No one was allowed to visit. Twelve days later, they were informed that he had died in the jail.

There was an inquest. On Nov. 4, 1948, the coroner, Richard Louis Duckett, released a one-page report. He concluded Thomas Falls had died of "congestive pulmonary oedema, acute maniac agitation and probable encephalitis." There was no mention of the bruises on his face or his two missing teeth, no mention of the straitjacket Falls had been confined in, possibly for days, according to what the family has learned.

The coroner also takes care to state, the death "was not due to a crime and not due to the negligence of any person." In the end, it was ruled a natural death.

"It was very hush-hush," Thomas Jr. said. "In those days, we had Premier [Maurice] Duplessis, and there was a lot of prejudice."

All these years later, he calls the treatment of his father police brutality — and he is certain his father was killed because of the colour of his skin.

"The racism is there."

Insidious racism

Historians refer to the Duplessis era as La Grande Noirceur, or The Great Darkness. In those days, a lot was hushed up, and there was very little oversight of public institutions. There was also blatant racism.

"The racism was insidious," according to Concordia University history Prof. Steven High. No matter where Thomas Falls went, "he would have been faced with the question of whether he would be served or not," said High.

In the Montreal of 1948, a landlord or an employer was legally entitled to refuse to rent to someone or offer them a job because of their skin colour — discrimination that was upheld by the Supreme Court of Canada in 1939, when it ruled that a Black man, Fred Christie, did not have a right to be served in a Montreal restaurant.

"Ninety per cent of Black people worked for the railways," until the 1950s, said High. Although there were plenty of factories in Little Burgundy, where a large number of Black people lived, few were hired there.

The options for Thomas Falls would have been limited in every way. Even so, High says, Falls probably came to Montreal seeking opportunity, since prospects for Black people in Nova Scotia would have been even worse.

Thomas Falls had been a popular man. A former Canadian Army and British military boxing champion, he was well known and respected in the Black community, both in his home province of Nova Scotia and in Montreal, where he and his young family moved after the war.

The war veteran had taught many boys boxing and regaled them with stories of his career. He liked to tell people he knew Joe Louis and had boxed with the U.S. champion.

The Advance, a now-defunct Nova Scotia newspaper, described how a local lawyer, whose sons Thomas Falls had trained to box, travelled to Montreal to try to help the family after the retired soldier's death.

Why were there marks of violence on the body of Thomas Falls just six hours after his arrest? J. Ross Byrne demanded to know. Why was he isolated in jail? Why did he not receive medical treatment? And how to explain the sudden death of a 32-year-old man who had been examined by a doctor just a few days before his arrest and had been "found to be strong in mind and body"?

Family members today say neither Byrne nor the family ever received any answers.

A family torn apart

With the death of Thomas Falls, his family fell into crisis. The four children were all placed in the child welfare system. The eldest, Thomas Jr., spent the next year with Daisy Peterson, the sister of famed jazz artist Oscar Peterson, whose father, Daniel, worked as a porter at the CPR.

Thomas Jr. eventually ended up in a boys' home. The other children were sent to live with friends and relatives. They were not reunited under one roof as a family for the next eight years.

Thomas Jr. is philosophical about the impact on the family of his father's death in police custody.

"I was basically in the dark," he said. Because he was so young — just six years old at the time of his father's death — he did not even go to the funeral.

There were no repercussions for the police officers who were involved, he said, and his father's story was never really told. All these years later, he would like to see his father's name cleared.

Systemic racism, intergenerational trauma

Despite the childhood trauma, Thomas Falls Jr. became a stationary engineer in the 1970s and says he managed to get on with his life.

But he says his family still lives with the racism that killed his father. It has affected his own children's lives.

"They just don't like police," he said. "They get stopped in their cars for this and that. It preys on them."

He says the only time he got in a fight was when he was very young and walking along Montreal's Ste-Catherine Street: someone used a racial slur against him, there was a street fight, and just like his father before him, he was taken to Station 25.

Years later, his son, Derek Falls, also ended up in Station 25. Derek says it was just one of at least a dozen times he's been racially profiled and stopped by police. He says each time brings back the stress of his grandfather's death. He says it's been hard on his children.

"They know their great-grandfather was murdered. And it's a scar that can never leave."

Derek's son, Gabriel, says the family wants to reclaim its history. They want justice for his great-grandfather, Thomas Falls. He believes, with the relevance of Black Lives Matter, now is the right time.

Racism 'was normal'

"I asked my grandfather about his experiences growing up as a Black man in Montreal during his time, the 1940s, until now," Gabriel Falls said. "He told me that nothing happened to him. I said, 'Are you sure, no one ever called you names?'"

His grandfather's answer shocked him.

"Oh yeah, many times I'd be walking around and people would call out n--ger and degrading things like that," he said. But, he told his grandson, "That was normal."

Gabriel Falls says racism can never be considered normal.

"For people like my grandfather and great-grandfather, these are just stories of a larger problem. That's what needs to be dealt with."

How could anyone ever thrive, he asks, "when they're treated like this, being called names daily? This is not healthy."

The Montreal police service did not provide any comment or information for this story.