Quebec wants to make school mandatory until 18. Will it work?

With more dropouts than any other province, another education minister attempts another overhaul

It's out with the old controversial Bill 86, and in with a new bold education overhaul.

Education Minister Sébastien Proulx told a Liberal convention on Sunday that it was time to put distractions aside and focus on the the success of students.

Bill 86, a lightning rod for controversy, was nothing if not a distraction for the Liberals, who were constantly defending its proposal to abolish school-board elections.

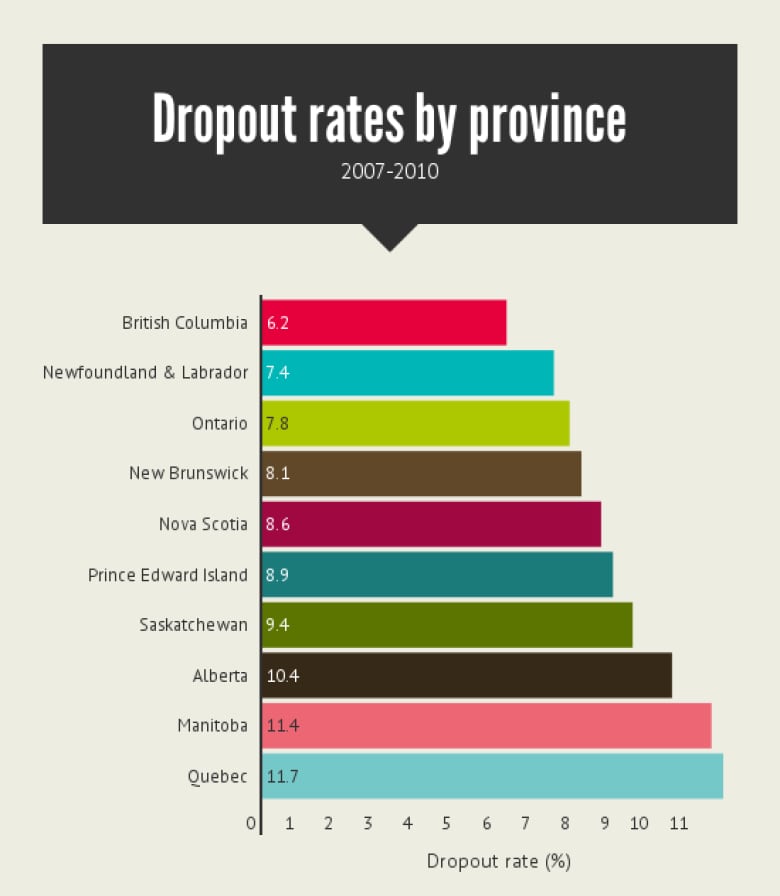

In its place, Proulx has promised an education reform bill that squarely addresses a lingering problem in the province — its sky-high dropout rates. Quebec has had the highest dropout rate of any province in Canada since 2010.

As a solution, Proulx wants to make school mandatory from four to 18 years of age.

Will it work?

If other provinces are any indication, making school mandatory until 18 could prove successful.

Ontario, which implemented the measure in 2003, saw its high school graduation rate increase from 68 per cent in 2004 to 84 per cent in 2014.

Quebec's, by comparison, went from 67 per cent to 71 per cent during the same time period.

Looking across the pond shows even more promising results. The United Kingdom made school mandatory until 18 three years after Ontario. Its graduation rate is now at 91 per cent.

How would it work here?

If the plan were to go through in Quebec, 1,000 to 1,500 more 16-year-olds would stay in school — and that's a conservative estimate, according to Égide Royer, a psychology professor at Laval University whose research partly influenced Proulx.

But making school mandatory to 18 should only be one element of a successful educational reform, Royer said. Another equally important element is early intervention for students who show learning difficulties.

That, however, costs money, and this government is set on austerity.

Despite recent injections of cash into Quebec school boards, many educators in the province have little confidence of the government's commitment to special needs education.

Recent months have been characterized by labour unrest and complaints of under-funding by Quebec's teachers unions.

- Teachers' unions warn class sizes, special-needs support at risk

- Montreal's largest teachers' group protests funding cuts

Unions skeptical

Before Proulx can hope to get people onboard with the reform, he needs to be clear on the amount of money needed and where it will go, according to Sylvain Mallette, president of the Fédération autonome de l'enseignement (FAE) teacher union.

"We cannot reform again without talking about the needs of the public school, of the resources it needs," he said.

"We were promised reform 15 years ago ... Instead, succeeding governments imposed cuts."

To quell Mallette's concerns and the skepticism around the government's commitment to funding mandatory education from pre-kindergarten to a high school diploma, the government needs to put its money where its mouth is.

For education experts like Royer, this means making education as a big a priority as health and sparking an education overhaul of Quiet Revolution proportions.

Though Proulx has indicated that he's ready to use all the human and financial resources necessary to give Quebec an education system to be proud of, we may not know for sure until the coming weeks when details are announced.